Two weeks ago, I wrote a Brief Summary of Actor Network Theory. I ended it by saying,

My next post will focus on ANT and AR’s different historical accounts of Western society’s relationship to technology. While Latour claims “We Have Never Been Modern” we at Cyborgology claim “we have always been augmented.” I will summarize both of these arguments to the best of my ability and make the case for AR over ANT.

The historical underpinnings of ANT are cataloged in Laotur’s We Have Never Been Modern and are codified in Reassembling the Social. I will be quoting gratuitously from both.

In We Have Never Been Modern, Latour comments on a debate between the political philosopher Thomas Hobbes and natural philosopher Robert Boyle. Latour describes the debate this way:

After Hobbes has reduced and reunified the Body Politic, along comes the Royal Society to divide everything up again: some gentlemen proclaim the right to have an independent opinion, in a closed space, the laboratory, over which the State has no control. And when these troublemakers find themselves in agreement, it is not on the basis of a mathematical demonstration that everyone would be compelled to accept, but on the basis of experiments observed by the deceptive senses, experiments that remain inexplicable and inconclusive.

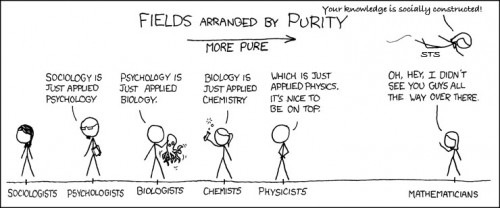

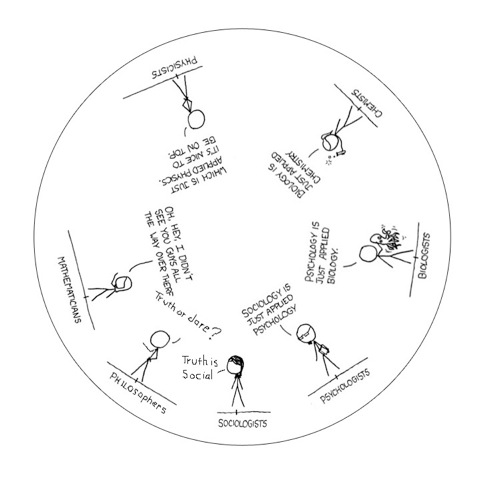

Hobbes (and Latour) do not like this separation of terms. Nature and society must be regarded as one thing. For Hobbes, taking nature out of society meant there was no clear authority on the workings of nature. One could only persuade others to agree on the same interpretation of sensory input. For Latour, the problem lies with drawing a hard line between what is social and what is natural. The hallmark of “Modernity”, according to Latour, is the rhetorical separation of nature (things) from society (citizens). Nature and society have never been separate, we just talk about them that way. What we need to start talking about are sociotechnical “hybrids” that bridge the human and nonhuman.

At this point, you may expect Latour to cite Haraway or at least position his own views on hybridity in relation to this prominent author. We have Never Been Modern, was published just two years after the Cyborg Manifesto.But, he engages Haraway in only the most shallow of terms. As Harding notes,

Donna Haraway gets perhaps three or four mentions in the two books to be discussed here. Valuable as her work is, such a tiny citation record is not sufficient to count as engagement with feminist science studies. His work is uninformed by Haraway’s arguments or those of any other feminist science theorist. He specifically discounts the value of what he refers to as “identity politics,”including many of the new social movements which have produced feminist and postcolonial science studies.

Instead, Latour (Reassembling the Social, p. 110) wants us to consider “nature” and “society” as “two collectors that were invented together largely for polemical reasons, in the 17th century.” This invitation to do away with nature and society, has to do with rhetorically and ontologically granting scientists the ability to see “things in themselves.” In other words, Latour believes that, when Enlightenment thinkers set up the “collectors” of nature and society, what they were really doing was limiting us to talking about our perceptions of nonhuman actors; their properties as objects, not their potentiality as subjects.

It is worth noting that there are precious few ANT analyses of information technology. This might be part of a larger problem that I have mentioned before: that Science and Technology studies is better equipped to talk about wooden planes than the Internet. But I also suspect that it is because when we really try to explain what is happening when a teenager deletes all of their Facebook posts every night ANT does not let us get anywhere new.

It is worth noting that Reassembling the Social does not even list “Internet” in the index. Beyond a few tentative steps into assessing ANT’s effectiveness as an Information Systems approach, there is almost no ANT literature that tries to describe what is happening on the Internet. In my summary two weeks ago, I demonstrated how ANT could describe wifi troubles at OWS. That description might have been semantically interesting, but it did not provide any kind of new or useful insight. Collins and Yearley said something similar when criticizing ANT’s ability to provide deep insight: When you strip away ANT’s provocative vocabulary, you are really left with nothing more than an “old-fashioned scientific story…The language changes, but the story remains the same.” I would suspect that an ANT analysis would result in nothing more interesting than the kind of uncritical analysis that Evgeny Morozov rightfully criticized in The New Republic back in October.

It may seem as though Augmented Reality (AR) is doing nothing more than extending ANT into the realm of the digital and the networked, but that is simply not the case. AR does something much different.

First, as the title of the blog suggests—we are deeply rooted in the project that Haraway started and that Latour largely ignores. This is evidenced most clearly in PJ’s piece on Trust and Complexity, the work we presented on the Cyborgology panel at #TtW2011, and Nathan’s piece on Digital Dualism versus Augmented Reality. It is clear that we are saying that technology is social, but not that the categories ought to be thrown out altogether. We are, instead, fascinated by the co-construction of society and technology and the new and complicated relationships they engender.

Second, as our subject matter shows, we are deeply committed to understanding this co-constructed world in terms of social justice, equality, and the emancipatory potentials of various socio-technical assemblages. This is seen in our continuing coverage of augmented revolution (both in the past as well as the present), Jenny Davis’ work on the gendering of Siri, and Dave Paul Strohecker’s posts on prosthetics and depictions of disability in the media. My work in gender and online cooking shows, mobile information systems in the developing world, augmented warfare, and the changing landscape of surveillance and sousveillance have also been motivated by topics that ANT shows little interest in.

Finally, in a reflexive turn, I want to acknowledge how we situate ourselves in relation to our interlocutors (i.e., versus Latour’s relationship to his subjects). The authors of Cyborgology have always tried to situate ourselves within our work. It is very personal work, in that we study cases we love, and we suspect that we love them because they are important in some way. We are developing a social theory of technology, using the very technology we aim to describe. Latour is totally absent from his own work, and it is by design. In his book Aramis: or, The Love of Technology Latour goes so far as to fictionalize and novelize his analysis so that he becomes but a character in a larger story. ANT says everything is connected in a seamless web, but when it comes to the author himself, he is always out of reach. Within that same book, he writes:

“You see, my friend, how precise and sophisticated our informants are,” Norbert commented as he reorganized his notecards. “They talk about Oedipus and about proximate causes . . . They know everything. They’re doing our sociology for us, and doing it better than we can; it’s not worth the trouble to do more. You see? Our job is a cinch. We just follow the players. They all agree, in the end, about the death of Aramis. They blame each other, of course, but they speak with one voice: the proximate cause of death is of no interest-it’s just a final blow, a last straw, a ripe fruit, a mere consequence.”

The larger project of Cyborgology has been to do the exact opposite. To say that information and communication technologies, broadly defined, have been under-theorized. The informants have much to tell us, but they do not provide the level of sophisticated analysis we need to fully understand what is going on here. We are bringing to bear, over a hundred years of social and political theory in hopes of better understanding how our information systems affect our social lives. In so doing, we believe that we can make both far better.

Follow David on twitter: @da_banks