Content Warning: Racism (anti-black racism, xenophobia)

Authors note: This is an analysis of images; I debated to what extent the images themselves should be included and how much description I should provide. In this sort of research, there is always a risk of re-circulating the violent discourse that the you intend to critique. Ultimately, and for a variety of reasons, I decided to include the images. I’m interested in readers’ thoughts on this question, so please post in the comments if you feel inclined to do so.

As with any ethnic or racial identity, whiteness is a multitude. White supremacy takes many forms. And, as Jenny Davis showed us earlier this week, it’s been a hell of a year for white supremacy.

Unless you are actively involved in white supremacist discourse communities, or find yourself a target of racist speech and violence, it can be difficult to envision these more hateful variations of whiteness. This invisibility makes it far too easy for some (and here I mean myself and many other white people) to underestimate just how much virulent racism exists all around us. This invisibility is two-fold: it tends to remain somewhat contained on forums like Stormfront or various “quarantined” subreddits, and we tend not to go looking for it.

There is great danger in this invisibility. First, the most disturbing variations of white supremacy can only remain invisible for so long before they start to spill out, as we saw last week when #blacklivesmatter protestors were attacked in two venues: one who was beaten at a Donald Trump event, and several others who were shot at a protest. Additionally, the invisibility and containment of extremist white supremacists makes it more difficult to draw straight lines between “subtle” forms of racism like wanting to close national borders to refugees and the more explicit forms that circulate in dark corners of the internet.

In what follows, I want to confront white supremacy head on. Visual rhetoric, the study of the persuasiveness of images, provides a useful tool for analyzing a wide variety of ideological formations. It is perhaps uniquely suited to analyses of digital cultures, which are replete with images. Below I conduct a rhetorical analysis of images circulated in two spaces; the first is the Twitter hashtag #whitegenocide and the second is 4chan’s “politically incorrect” (/pol/) board. I’m particularly interested in how the affordances of the two platforms, Twitter and 4chan, encourage different varieties of white supremacist images.

The primary difference between the two spaces is that one is primarily pro-white (#whitegenocide) while the other is primarily anti-black (/pol/). It’s key to understand that this is not necessarily an ideological difference—both sites are simultaneously pro-white and anti-minority. Rather than an ideological distinction, it’s more useful to analyze their differences as one of emphasis or articulation. In other words, the worldviews expressed in these spaces have only slight differences. It is really the modes of expression that differ, and these modes are in part informed by the differences between the platforms themselves. While tweets are associated with stable, often public accounts with personally identifying information, 4chan is anonymous and posts cannot be tied to individuals’ offline selves. The result is that #whitegenocide engages in a greater degree of “acceptable” white supremacy, while 4chan users can be more “obviously” racist.

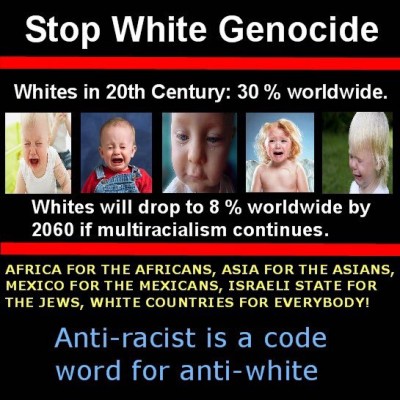

The image above provides a good starting point for understanding #whitegenocide. Crying white babies are included to emotionally prime viewers for the seriousness of the purported problem, the disappearance of the white race. The blame for this extinction of the white race is “multiracialism,” a term that is effectively persuasive in its ambiguity. It has an air of legitimacy without needing to define itself. The phrase “Africa for the Africans…” etc. refers to the presumed double standard that non-white countries are excused for being racially homogenous while white nations are expected to become increasingly heterogeneous—an argument that conveniently elides centuries of colonialism in which the entire world became a white playground and site of resource extraction. Finally, the image dismisses all anti-racist activism as anti-white “reverse racism.” The short phrase does a surprising amount of work: it asserts that 1) reverse racism exists, 2) the only racism now is anti-white racism, 3) all of this is somewhat conspiratorial and encoded.

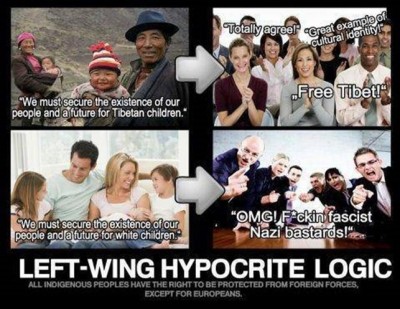

This image makes a similar argument, appealing to the protection of children. It dismisses “left-wing” logic as internally inconsistent without needing to acknowledge that, while Tibet is actually facing the possibility of being wiped off the face of the earth, Europe… well, isn’t. It’s not happening. The last panel launches a three-pronged assault against leftists, undermining their overly-emotional and unreasonable anger, their use of labels like fascist and Nazi, and (I’m pretty sure?) their use of internet abbreviations.

Here we see what looks like Keith Olbermann (who hasn’t worked at MSNBC since 2011, but I digress) calling the GOP racist, while another white guy, possibly Bret Baier but who could potentially be any white guy from Fox News, calls for legal immigration. This is another triple threat—a critique of mainstream news media, the assertion that both the left and the right are calling for white genocide by supporting immigration, and of course two scared white kids. Scared white kids is a pretty common theme.

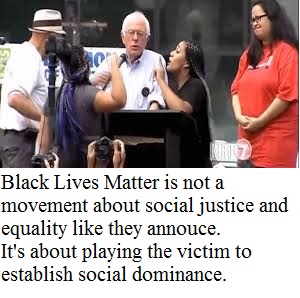

Moving on to /pol/ we see greater emphasis on Black Lives Matter, particularly in the wake of the recent shooting in which two 4chan users from /k/, a weapons board, provoked protestors and, upon being crowded away from the protest and allegedly punched, shot at least 5 people. The image from the Bernie Sanders campaign event, in which BLM activists interrupted Sanders, was widely criticized by his supporters. The claim that a movement built on raising awareness about and countering disproportionate police violence against black Americans plays into many of the same fears present in #whitegenocide, namely the decline of white power. It’s a bit more crude than those shared on Twitter, perhaps because 4chan is “speaking to the choir” where persuasion is more internal than outreach-oriented, and so the messages do not need to be as finely crafted.

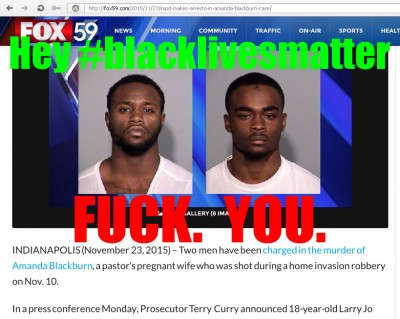

This image features a news report and mug shots of two black men who murdered Amanda Blackburn, a white mother pregnant with her second child. The connection between the murder and the BLM movement, though completely unrelated, suggests that black-on-white crime delegitimizes a movement that primarily addresses police brutality. The fact that Blackburn was a pregnant white woman makes her a particularly sympathetic subject. Like the last image, this is more crude than most of the images featured in #whitegenocide.

This one was new to me. Pepe the frog is a popular meme, especially on 4chan. This particular Pepe is Smug Pepe. Only now he’s Smug Trump Pepe. This image was posted in a thread defending the BLM protest shooters, accompanied by text using a derogatory term for black protestors. The poster expresses their hope that protestors will become violent, thereby delegitimizing the movement as a whole, and that the shooters, “brave Pollacks,” will be acquitted on grounds of self-defense. The connection between the text and Donald Trump goes unstated, but is a good fit given Trump’s racist campaigning. It’s an inside joke, a rhetorical device that fosters in-group solidarity rather than attempting to persuade outsiders.

There are several images from 4chan that I decided not to include because they are just too vile, but they’re worth mentioning. One featured Michael Brown, whose shooting sparked the Ferguson protests that began in August of 2014 and was a major contributing event to the ascendance of the BLM movement. Brown’s image was accompanied by various dehumanizing stereotypes. Also featured were images of Hitler and Nazi regalia, offensive caricatures of Jewish people, an historical photo of a lynching, and unflattering images of black Americans designed to make them look dangerous or frame them as objects of ridicule. The thread also contained many slurs and calls for black genocide and the rollback of civil rights.

The #whitegenocide images differ rhetorically from the /pol/ images in at least two important ways. First, as mentioned above, they are connected to stable accounts that often contain identifying information. As such, they tend to be less explicitly racist and more about advocacy. Using statistical data about the trend towards a white minority and fear for the future of white children, they combine supposedly rational argument with emotional appeal. These are two of Aristotle’s three means of persuasion: logos, the appeal to logic; pathos, the appeal to emotion; and ethos, the appeal to the authority of the speaker. Aristotle defined rhetoric as the ability to see the means of persuasion, and argued that rhetors should assess their arguments and the employment of these means depending on their audience and their goals. These are tactics that many of us use almost subconsciously when trying to craft an effective argument, and more sophisticated rhetors use them quite purposely to ensure their arguments have the intended impact.

Secondly, the #whitegenocide images are employed in ways that attempt to convince outsiders of their arguments, while /pol/ is much more oriented toward reinforcing group solidarity among those who already agree with their positions. By using statistics and emotion in ways that are on the surface less explicitly racist—by emphasizing advocacy rather than virulent dehumanization—the nature of persuasion changes dramatically. And these facts reflect the variations of white supremacy more broadly. While the Ku Klux Klan has historically operated in secret—though that fact is changing a bit—the Tea Party movement and the GOP rely on dog-whistle racism to present ideas that, while existing in the same ideological universe, are made more palatable to the public at large. As the cultural climate changes toward or away from xenophobia and other forms of racism, the extent to which white supremacy can reveal itself also shifts. We present ourselves differently to co-workers, family, friends, and strangers depending on how much we value their opinion of us, how likely they are to agree with our views, and how easily we can be held accountable for our opinions. In addition to all of these factors, the cultural acceptability of certain opinions changes over time (and not always in a progressive direction), adding another factor to the variety of rhetorical performances.

These are the faces of white supremacy. We can’t let them hide, and by ignoring them we give them the chance to flourish.

Britney is on Twitter.