Image via TechCrunch

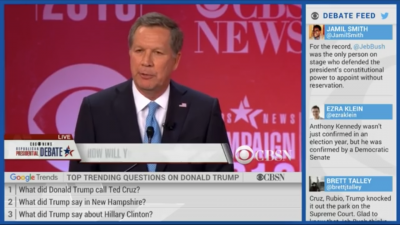

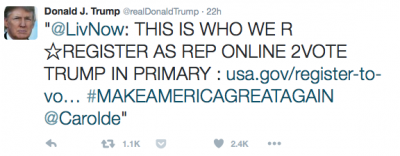

“How tall is Jeb Bush?” This was the question on (apparently) many people’s minds leading up to the February 13th CBSN GOP debate. Thanks to Google, in partnership with CBSN, we now know that Americans are asking the hard questions, like “What is Ted Cruz’s real name?” “Why did Ben Carson wait to go on stage?” and, of course, a real deal breaker for me as a voter, “How old is John Kasich’s wife?”

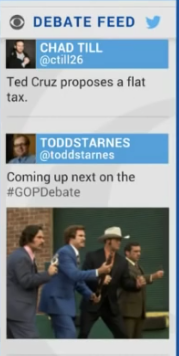

The integration of mass media broadcast and social media platforms has shaped the way Americans engage in electoral politics. Debate coverage this election cycle has included solicited questions via Facebook and YouTube, anchors and pundits reading tweets on air, and live coverage of debates from corporate social media accounts. February 13th’s GOP debate was a stunning example of how social media and the Internet have shaped broadcast news. For the entire debate, two graphic overlays displayed information from Twitter and Google. The Twitter live feed featured tweets curated by CBSN that, by and large, featured the #GOPdebate hashtag and offered a range of commentary, summary, fact checking, and humor.

What did Trump say about ______? is a pretty good summary of his campaign.

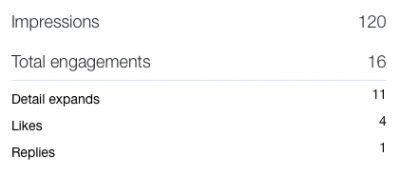

The Google bar at the bottom of the screen switched between two topics: search trends over time and popular search questions. A bar graph showed the “search interest” trends for the top three candidates at the time (consistently Trump and Cruz, with Bush and Rubio swapping places occasionally). Every 30 seconds or so, the bar graph was replaced with the “top trending questions” on each of the candidates. Well, all except for Marco Rubio, who never got a set of top trending questions, for reasons that I’m sure are fascinating and nefarious.

I do not know how this information is meaningful.

The relationship among these three entities—CBSN, Twitter, and Google—are by and large mutually beneficial. Twitter, which has been facing death knells for quite some time now, gets to remind the country that yes, people are still using Twitter, and doesn’t it look exciting? Google also gets its logo on the screen for the entire debate, while showing off its analytic capabilities. And CBSN gets content from both of them to accompany the debate. There is undoubtedly some sort of monetary relationship among them as well, though if this information is at all available I have been unable to find it.

These sorts of strange bedfellows arrangements are nothing new. They’re akin to what Daniel Boorstin called “pseudo events,” also commonly referred to as “media events.” Boorstin defined pseudo events according to four characteristics: 1) they are not spontaneous, but carefully planned, 2) their immediate purpose is to be reported on by the media, 3) they have an ambiguous relationship to reality, and 4) they are intended to be a self-fulfilling prophecy—a pseudo event simultaneously makes a claim and makes that claim real.

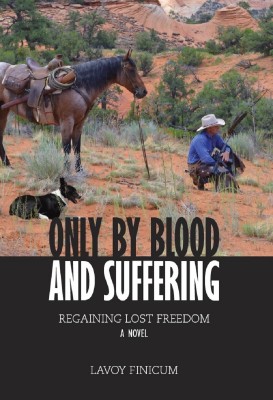

Boorstin gives the example of a hotel that’s looking to increase its prestige and, subsequently, its income. Rather than improving the accommodations, they hire a PR firm who tells them to use their upcoming 30th anniversary as an opportunity to drum up attention. The hotel partners with leading community figures—prominent bankers, lawyers, and members of society—to draw attention to the event. The hotel makes the case for its prestige by holding a 30th anniversary banquet attended by important people and covered by the media and, in so doing, proves itself to be prestigious. Sometimes pseudo events fail spectacularly, as in the infamous 2012 Mitt Romney food drive in which the campaign purchased canned goods and gave them to supporters so they could be filmed giving the cans directly to Romney. Unfortunately for him, the media event revealed itself to be a farce. It backfired quite forcefully in his face, exacerbated by the fact that the Red Cross does not even accept canned food donations. Oops.

Image via Yahoo News

But the Twitter-Google-CBSN partnership, and others like it, is different from Boorstin’s media events in important ways. While it is planned, it also relies on an element of spontaneity to make it interesting. The inclusion of the Twitter feed and up-to-date Google analytics gives the event a sense of movement and dynamism. Of course, to keep it from getting too spontaneous, the Twitter feed is curated, and moments like the MSNBC Iowa Caucus F-Bomb can be gracefully avoided.

What we have in these mass/social media partnerships is an extension of Boorstin’s media events. I call them new media events, and offer a few preliminary observations on the characteristics of new media events:

- Semi-planned: some elements are carefully crafted while others remain dynamic, shifting according to changing circumstances and content availability

- Multi-media: users and curators piece together text, photos, videos, and other mediums to tell a story

- Free content generation: corporate media entities rely on users to produce free content

- Contextual: rather than being mired by context collapse (PDF) or conversation smoosh, events are centered on a specific topic, and content is curated as such

Unlike (old?) media events, new media events are less about building prestige for a certain business or political entity and more about fostering engagement between media producers and audiences to increase revenue for corporate partners. They walk a fine line between being perfectly choreographed and algorithmically generated, with a curatorial middle person selecting content that is generated “from below” that suits the interests of the event sponsors. Their primary purposes is not to be reported by news outlets, but to be circulated by audiences themselves.

New media events aren’t just for presidential debates. For example, Twitter Moments share the same characteristics, and were created to combat many of the problems of context collapse and conversation smoosh mentioned above. Facebook trends perform a similar function. Reddit AMAs also exhibit the qualities of new media events described here.

Media theorist Marshal McLuhan, and later Bolter and Grusin in their book on remediation, argued that new media are always mediations of old media. Writing mediates speech, moveable print mediates writing, digital text mediates the printing press, film mediates photography, and so on. Digital media are hypermediated—they remediate all of these, fostering for the rich semantic space of multi-media interaction. For McLuhan, the significance of any new medium is the ways in which it extends the human sensory experience, the “self,” outward. Without any mediation (speech, writing, etc) we exist only within ourselves. As new media extend the boundaries of exchanges of thoughts, we stretch and grow, and in the digital age our selves extend all across the world.

This extension is key to new media events. Every entity involved—from Google to the searchers asking how tall Jeb Bush is, from Twitter to the tweeters themselves—uses the occasion to grow itself. Hashtags introduce the tweet, and the tweeter, to a larger audience. CBSN then extends that moment of mediation to its entire audience. So tweet, and use the hashtag of course, and watch yourself grow. McLuhan would be so proud.

Britney is on Twitter.