This is the year of #BlackLivesMatter. In response, it is also becoming the year of White Supremacy. It’s not that Black Lives didn’t matter before, nor that Whiteness didn’t reign supreme. Rather, dramatic and highly publicized incidents of violence against Black citizens by those charged with protecting them have created a cultural dynamic in which the value of Black Lives and the respondent assertion of White Supremacy, have reached a point of articulation.

When you clean house, the roaches emerge. As a nation, we are cleaning house, finding and scrubbing out the blaring and hidden spots of racism, many of which have seeped deep into the layers of our social fabric. A White Supremacist presence is therefore unsurprising. The Supremacists wriggle out in defense of their comfortable home that the elbow grease of mobilization threatens to upend. They are gross but expected. However, their pervasiveness and seeming capacity to garner sympathy, is less expected.

The affordances and dynamics of social media tell an important part of the story…

Counterclaims about both Black Lives and White Supremacy are facilitated by social media platforms that afford the formation of issue driven groups with the capacity to commiserate, strategize, and spread a unified message. Such was the process by which the successful movement at Mizzou, in which Black students and allies mobilized to achieve administrative resignations along with policy and curricular changes, translated with near immediacy into similar movements across college campuses in the U.S. #StandwithMizzou became a rallying cry for students who wished to affect real change in their own schools’ racial climate.

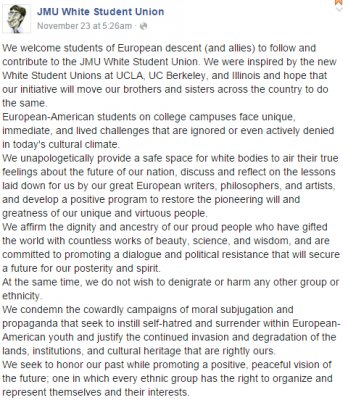

These very same processes are also those that currently facilitate the fast formation of White Student Unions, reactionary groups created by and for “White students and allies” who fear the loss of White’s voices and decimation of White culture. Although administrations are quick to denounce the groups as unassociated with and unsanctioned by the universities to which they are connected, the groups are nonetheless collectivities of people, most likely students, who gather to assert their White Power. The group that popped up at my university describes themselves as follows:

Rather than identifying as White Supremacists, the profiles operate under the gauze-thin cover of European identity. These are White European students, emboldened to speak their (racist and ethnocentric) truth.

The question, then, is from whence does such boldness arise? Given the widespread demonization of Whiteness identity groups in the U.S.—especially the KKK—how do a bunch of 20 year olds come to think it’s viable and acceptable to form a group around White heritage? And while we’re asking, how do four adult men, in 2015, identify as White Supremacists, scream racial slurs, and shoot into a crowd of protestors? This is the part of the story that social media doesn’t fully capture.

Racist collectives, with their communities, identities, and calls for action, form and flourish with the symbolic aid of highly visible, highly powerful, and highly influential figures, given voice through America’s political institution.

White Supremacist messaging, though animated by grass roots social media groups, is undergirded by the rhetoric of those in the highest positions of power. For instance, FBI director James Comey, who blamed #BlackLivesMatter protestors for creating a hostile environment in which police officers are disinclined to intervene, lest their actions get filmed and critiqued. Or the list of governors who (are trying to) refuse Syrian refugees entry into their states. And of course, Donald Trump, who not only represents Whites who are concerned with the slippage of their power, but like Comey and the governors, legitimates the White Supremacy position.

Comey and the anti-refugee governors foil their racism in security concerns. This breeds hate and exclusion, but can ostensibly diminish with time and data, or at least migrate to new groups as new moral panics emerge. Trump’s hate is stickier. It plays more to the long game. It’s based on a feeling—an intuition of discomfort–and its expression is attractively packaged in authenticity.

Authenticity is an ingrained American value, all the more valuable among politicians from whom we are accustomed to, but sick of, seeing precisely calculated performances. Trump is the candidate who purportedly “tells it like it is,” who isn’t enchained by political correctness. He is the folk hero who promises to “make the country great again!”

With the valor of authenticity, Trump says things like “The wall will go up and Mexico will start behaving.” He insists that Muslim Americans in New Jersey were celebrating after 9/11—a claim he vehemently defended by mocking a reporter with a congenital joint condition. He also tweeted statistics about race and murder that are entirely fabricated, imply that Blacks are disproportionately violent, and relies on “thug” iconography. And he continues to do great in the polls.

By wrapping their hate in safety and “truthfulness,” these leaders gift racists their righteousness. Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric does more than collect support, but also provides a moral position and an accompanying narrative on which to carry messages that would otherwise be unpalatable. Messages like those from White Student Union organizers, or anti-refugee protestors, or Men’s Rights Activists, or assholes on Yik Yak.

Openly racist leaders make it acceptable for everyday citizens to hold racist views and viable for everyday citizens to engage in racist acts. When the FBI director worries about police safety and effectiveness and a presidential candidate shouts about Mexicans, racism becomes an expression of morality–one of safety and truth– an expression that spreads and takes hold on the digital platforms of everyday life.

Jenny Davis is on Twitter @Jenny_L_Davis

Headline image source