What if you could combine the unstoppable power of good-old American entrepreneurialism with the force of dank memes to create a revolution? That’s what Oculus Rift founder Palmer Luckey wanted to do. He wanted to bankroll an organization founded by moderators of Reddit’s r/The_Donald, a 501(c)4 non-profit called Nimble America. But the organization’s roll out and first real fundraising drive on the subreddit did not go as planned. The_Donald supporters were not having any of it.

Despite headlines like “Oculus Rift Founder Palmer Luckey Funding Trump Shitposters” there doesn’t seem to be any evidence that the group has funded anything substantial. It is far from clear that Luckey Palmer is “secretly funding Trump’s meme machine.” Their financial documents indicate that they never raised more than $10,000 in a single donation, and never had more than 1,000 in their coffers at a given time. While I don’t know what the going rate for shitposters is, I can read their readily available financial statement and see that no Pepes were purchased—just legal services (the bulk of their expenditures), a website, an “educational” billboard, and a Facebook ad. And despite claims that “Nimble America operates the Reddit channel r/The_Donald,” they were in fact run out on a rail, and the incident ended with a moderator associated with Nimble America resigning his post and promising that “Nimble America will continue but it will be completely independent from /r/the_donald. There will be no further solicitations for the cause.”

It would be a nice story for the left if the rise of the alt right in mainstream discourse and the appearance of Trump-loving Pepes across the internet could be explained away by astroturfing, but that simply isn’t what’s happening. And if the lefty press got it wrong, Nimble America got it even more wrong. The backlash against them on r/The_Donald is ongoing, and the incident reveals a deep misunderstanding of the role of the internet and memes in this election season.

Memes are not a commodity, a sentiment already being parodied by /u/PEPE_Price_bot, a bot on The_Donald that tracks the nonexistent price of nonexistent Pepe shares. For The_Donald, the idea that a millionaire like Luckey could come in and bankroll the subreddit, turning their community into a “meme machine” was not only absurd but offensive. Users responded that they were proud to shitpost for free, and compared Nimble America to the pro-Clinton Super PAC Correct The Record, which has been criticized on both the right and the left for paying people to post on social media and argue with Clinton’s detractors.

The Nimble America effort dramatically miscalculated on two counts. First, the fierce populism that undergirds the Trump movement rejects any attempt at co-optation. While Trump himself may be wealthy, his supporters as a whole are very suspicious of, even hostile towards, anything smelling of the political elite. Reddit Trumpers felt that Nimble America was trying to take credit for their relentless shitposting and the memes that they have spent so much free labor creating and circulating.

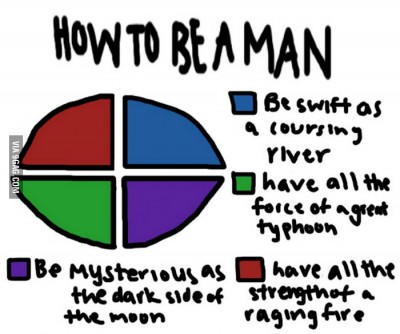

But the second miscalculation concerns the distinction between paid-for advertising and the meme economy. Many The_Donald supporters replied to the fundraiser by saying that people should only donate to Trump’s campaign directly, or buy their merch, or set up your own website posting memes. They are aware that memes operate in a different market than advertising, one that doesn’t rely on middle-man firms soliciting donations and then, in all likelihood, not being held accountable for the use of those funds. Memes are free. Shitposting is volunteer work. This isn’t an economy of currency, but one of attention. And injecting memes into the mainstream discourse doesn’t require a PAC; Trump will just tweet them out himself.

The Nimble America debacle is an allegory for this bizarre election writ large. Sanders raised enormous, unprecedented campaign funds without the use of Super PACS. A reality TV show star and human sweet potato beat some of the biggest names in Republican politics and is now running a very viable campaign, and using racist memes to do it. Clinton is desperately trying to win over millenials but coming off more like this guy. The memers refuse to bought, and the Pepes refuse to be sold.

But, to me, the biggest takeaway from the allegory is how wrong the liberal press got this whole story. Without any evidence beyond what the Nimble America representatives claimed, the assertion that they somehow bankroll the alt right meme machine and control a subreddit picked up steam quickly, not unlike Clinton’s flawed Pepe explainer. An hour spent scrolling through Reddit threads and 5 seconds looking at their financial documents show that they are not some political meme powerhouse. They don’t run anything except a mediocre website and a single Reddit thread in which they were shown the door. Oh, and a billboard.

Opponents of Trump do themselves a serious disservice with this kind of reporting. For two days, The_Donald has been covered with memes and jokes about the inaccuracies and over-blown charges made in the publications linked above. It further feeds their narrative that “SJWs” are divorced from fact and will say anything to stop their Dear Leader. It gives them power. And many, many lulz.

This essay could not have been written without the help of my colleague and bestie Nick Hanford, who provided many of the articles cited, read through a draft of this essay, and Dmd me on Twitter all morning with helpful ideas. As thanks, I will close with this music video that he cherishes.

Britney is on Twitter.