*~* “Teach with TSP” Contest Winner, 2018 *~*

One of the ways that The Society Pages can be really useful for teaching is for finding ways to connect recent events in the news to larger sociological conversations in the classroom. Today’s suggestion shows one way to use “There’s Research on That!” to do just that: without necessarily assigning any of the readings to the students, the instructor can find a topic of relevance and use the academic resources included in the TROTs post to quickly catch themselves up to speed on the recent sociological literature in order to facilitate a stronger class discussion. This is a great way to keep classes relevant and to keep ourselves current in the field.

Recently a Texas court ruled the Indian Child Welfare Act (ICWA) unconstitutional. This topic would be of interest in a variety of sociology courses: Family, Law and Society, Race and Ethnicity, Social Problems, and Intro to Sociology units on institutions.

Materials:

You bring:

- Projector/internet/resources to show a streaming film in class

- Link to the documentary

- Read the TROTs resources ahead of time

- Prepare and print copies of a worksheet with some questions (suggestions below) connecting the ICWA with contemporary and historical experiences on Native people in the United States

- Paper copies of a news article about the Texas court decision striking down the ICWA (unless you want to assign it in advance or have students read together in class)

Students bring:

- Any reading you want to assign in advance

Instructions:

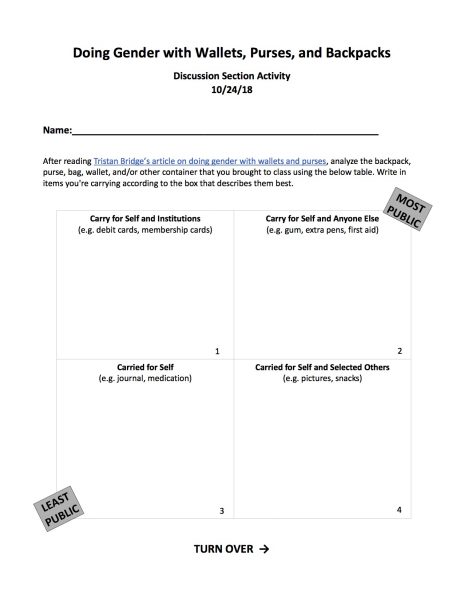

- Ask students to read a news article about the Texas court ruling that the ICWA is unconstitutional. You can either have everyone do this together at the start of class or assign this to be read in advance, but in all cases ask students to take written notes on anything they don’t understand or have further questions about.

- Ask students if they have any immediate comprehension questions about the news article. For example: if they didn’t understand a word or basic concept, then those questions should be answered. Otherwise, tell students to keep their questions in mind during the documentary. The questions should help the students connect the contemporary to the historical.

- Show the first 40 minutes of the PBS Documentary “Unspoken: America’s Native American Boarding Schools.” The documentary streams for free online. Its full length is 56 minutes but I don’t recommend the last 16 minutes for this activity as it is not focused on boarding schools and will probably distract class discussion. Ask the students to complete the worksheet while they watch the documentary, which will again help make broader sociological connections between the historical experience of boarding schools and contemporary foster care systems and schooling. Actively using the worksheet also teaches students to be more active watchers of content.

- Use the answers on the worksheet AND the questions students wrote on the news article to launch a discussion. A good prompt for starting a discussion after an emotional video like this one can sometimes be to first let students just react to the content (ex: “how did it make you feel?” or “what did you think?”) before trying to get them to think too analytically.

Worksheet Question Suggestions

- Did the documentary answer any of the questions you wrote beforehand?

- What is the Dawes Act?

- List 3 dates you heard and what happened on those dates. (You as the instructor can use these to have students construct a timeline later for a more extensive activity if you want. These can be a really useful for active learning and to really have students visualize how long certain periods lasted in relation to how little time has passed since then.)

- How long did American Indian boarding schools run? When were they closed?

- Give one example of resilience from the documentary.

- What surprised you?

- What does assimilation mean? How does it relate to American Indian boarding schools? To the Indian Child Welfare Act?

- There are more ideas for discussion on the PBS website of the documentary.

Additional Resources

- The Standing Rock Syllabus is an invaluable teaching resource

- Additional TSP TROT post on Settler Colonialism and Minnesota’s “Wall of Forgotten Natives”

A special thank you to Bret Evered for her invaluable pedagogical knowledge and assistance with this activity.

Dr. Meghan Krausch studies race, gender, disability, and other forms of marginalization throughout the Americas and in particular how grassroots communities have developed ways to resist their own marginalization. Read more of Meg’s writing at The Rebel Professor or get in touch directly at meghan.krausch@gmail.com.