In keeping with the theme Hollie started about what to do on the first day of class, I’ll share two activities that worked well in my first class of Intro to Sociology:

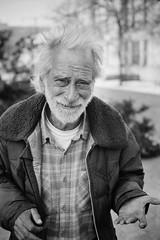

1) I have a small class this summer (23 students), so I had the time this semester to do student introductions. I wanted to use these introductions as a way to get students to start thinking about their social location. After a short lecture on the basics of sociological framework and the importance of examining context, I had students first go around the room and introduce themselves by name. Then, I asked them to add a little “context” to their introductions. Who are they? What experiences have shaped how they see the world? Instructions to the students:

- Introduce yourself!

- First, tell us your name (what you would like to be called).

- For all subsequent rounds, introduce yourself further by adding context. Tell us something about your context (what has shaped your view of the world):

- Who you are, your background, your family, your interests, what you like to do, who and what you identify with, your heroes, activities you do or used to do, why you are in college, your goals, places you have worked, etc.

Go as many rounds as you’d like (I did two). If students start to simply name their interests, start asking them how that interest may influence how they see the world to direct their thinking back to their own social location.

2) Next, I reviewed the basics what sociologists study. Then, to get students to start working out their own sociological imaginations, I had them spend five minutes jotting down their own sociological questions and then had everyone share at least one of their questions with the class.

Activity: Sociologists attempt to answer questions we have about the social world. What are some questions you have about the social world?

In a Word Doc (hooked up to a projector so they could see it), I wrote down all of their questions so that we could come back to them throughout the semester to see if they had gained the tools to know how to answer them. If they asked questions that weren’t particularly sociological (for example: one student posed a question about renewable energy), I asked them to think about the social dimensions of this problem (e.g., business interests, capitalism, funding for scientific discovery, etc.)