With so many concerns about voter suppression in the 2018 midterm elections, now is an excellent time to highlight the important role that social science can play in public debate and in our classrooms. Today’s suggestion for Teaching with TSP is a group exercise using King and Roscigno’s special feature on the 50th anniversary of the voting rights act that can be done during class followed by a discussion with the whole class. I used this exercise in my lower division Race & Ethnicity class, but it could easily be used in other lower division classes like Introduction to Sociology or Social Problems, or in an upper division Political Sociology class with some additions and modifications (which I’ll explain below). This exercise is ideal for a course in a general education curriculum that meets a social sciences requirement where instructors are often tasked with teaching students how to assess different kinds of information, evaluate evidence, and understand biases. I like this exercise because it leaves room for students with differing levels of ability, and because it directly and constructively engages students who hold the belief that everything taught in Race & Ethnicity or other sociology classes is “biased” or based on “differing opinions” without attacking them.

Materials:

You bring:

- Printed copies of the article (1-4 copies per group)

- Whiteboard and a bunch of markers

Students bring:

- A copy of the book or other text you have recently read in your class

- Pen and paper

Instructions

- Place the students in groups of 4-5 and give each group at least one copy of the article. Make a section on your white board for each of the different terms: 1) an opinion, 2) an empirical fact, and 3) a social scientific claim. Ask students to read through the entire article and, as they go, to identify two of each: an opinion, a fact, and a claim. They will need to write each of these on the board as they find them. You may want to make the rule that no repeats are allowed since that sometimes helps people work a little more quickly in groups (but this may not work if you have a larger class and a lot of groups).

- As students fill the board and work through the exercise you can choose to either let incorrect answers stand or you can go talk to the groups and ask them to fix those answers in the moment, depending on the dynamic and size of your class.

- Students are likely to come up with good questions about the difference between these three terms for you and each other while they work through the exercise, keeping in mind that part of what may be new here for college students is the addition of the “social scientific claim.” While K-12 does teach a related skill, it tends to focus on fact vs. opinion, which leaves evidence-based arguments in a confusing gray area for many new college students. Furthermore, many of us know that observable empirical facts in sociology are often nonetheless controversial. This exercise opens up that fact for conversation directly from an unexpected angle.

- Groups that finish early complete the same exercise using the most recent course reading, until all groups have at least finished the main exercise.

- Gently correct or clarify anything from the answers on the board. Transition from small group activity to large group discussion by asking “What do you notice when you look at the answers on the board? Does anything jump out at you? Anything surprise you? Confuse you?” This gives students a moment to reflect on what all the groups did. By asking students to choose the direction, you allow them to take ownership over the activity and lead the discussion in a direction that’s interesting to them, and the result is a more engaged, productive discussion that will allow students to tell you what they know and don’t know about the topic and what they want to know more about. More ideas for discussion are below, along with possible modifications to the exercise.

Discussion Guide

- Is voter fraud a problem? (Establish that given this article and exercise the students understand that it is not a problem.) Why do you think so many people think it IS a problem? Did you think it was (more of) a problem before today?

- Explore students’ reactions to why voter ID and other voting access laws are being changed, especially since voter fraud isn’t a problem. Do they agree with the authors? Are they unsure of the reasons? Can they develop their own sociological hypotheses?

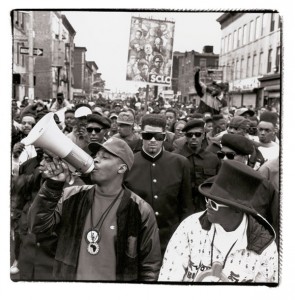

- Discuss the history of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Civil Rights Movement. What did students learn that was new? Do they have questions or reactions? Is there a reason these changes are happening now?

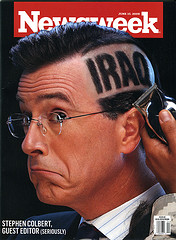

- What is the role of social science and sociology in politics?

Possible Modifications

- Students could be asked to update this piece or to make it local by researching the requirements to register and to vote in their own state.

- If you are in a state with voter ID legislation, students could research who introduced and supported this legislation, what challenges have occurred to it, and the judicial opinions that have been issued.

- Either of these could be done as part of a class activity or as a homework assignment.

Additional TSP Reading on Voter Suppression

How Voter Suppression Shapes Election Outcomes

Strict Voter Identification Laws Advantage Whites—And Skew American Democracy to the Right

—

Dr. Meghan Krausch studies race, gender, disability, and other forms of marginalization throughout the Americas and in particular how grassroots communities have developed ways to resist their own marginalization. Read more of Meg’s writing at The Rebel Professor or get in touch directly at meghan.krausch@gmail.com.