Last week the controversial killing of 29-year-old Mark Duggan by police in North London was ruled lawful by a jury. His killing sparked riots across London and elsewhere in England. To many, it seemed like another unnecessary killing of a young man found prematurely guilty in the minds of police by virtue of the color of his skin. While the court case is over, many still believe that Duggan was murdered without cause.

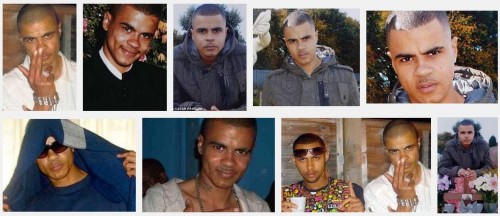

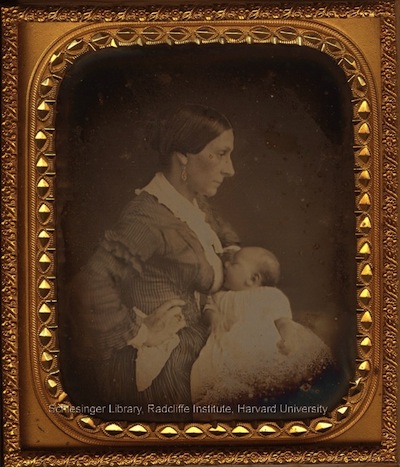

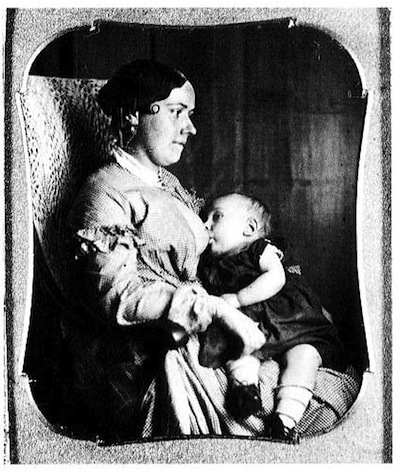

In the meantime, the news covered Duggan’s case quite extensively and, while there is a lot to say, here I want to draw attention to how the story was illustrated. A Google search for his name offers a glimpse into the many faces of Duggan, as uploaded by the media. Outlets choose which to picture to include, ranging from a smiling face with cherubic dimples (upper left), to a posturing blue “hoodie” photo (bottom left), to the stoic stare with a knitted brow (upper right hand corner).

Each of these, together with a headline, potentially leaves the reader with a different impression.

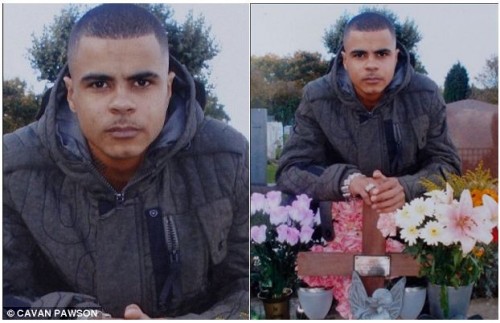

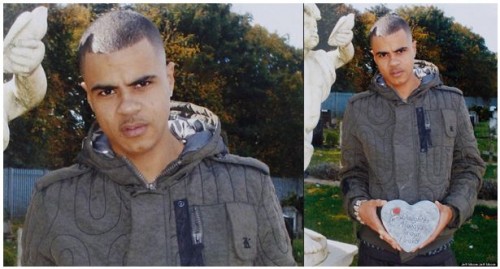

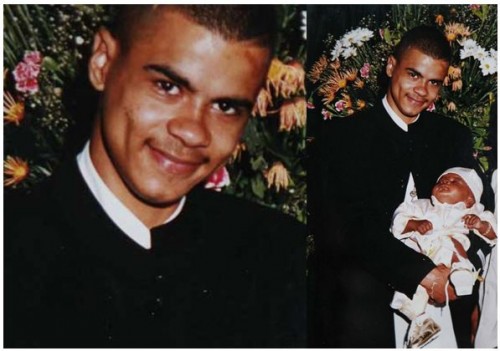

Cropping matters too. You might notice that third image from the left in the top row is a cropped version of the bottom right. Two other frequently used photos were also cropped. All exclude connections to others: a visit to a grave site, a plaque commemorating a daughter (“Always in our hearts”), and a baby in his arms.

It may make journalistic sense to exclude context and focus on the individual. Likewise, I don’t know why some photos were chosen over others and surely there are factors that I’m unaware of. So, I don’t mean to criticize the media agents making these decisions. I do want to draw attention, though, to the fact that these decisions are being made. And they inevitably color our reading of the news stories they accompany.

Hat tip to Feminist Philosophers.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.