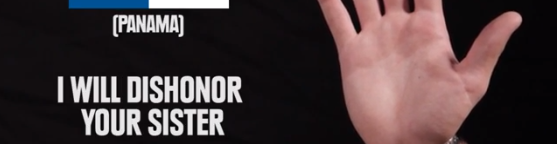

The phrase “social construction” refers to the fact that things, symbols, places, sounds — basically everything — is devoid of meaning until we, collectively, agree as to what something means. Once that happens, it has been “socially constructed” and we can refer to it as a “social construct.”

The phrase “social construction” refers to the fact that things, symbols, places, sounds — basically everything — is devoid of meaning until we, collectively, agree as to what something means. Once that happens, it has been “socially constructed” and we can refer to it as a “social construct.”

The fact that gestures have any meaning at all, and that they can have different meanings in different places, is a simple example of this basic sociological concept. Enjoy this one minute compilation of examples!

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.