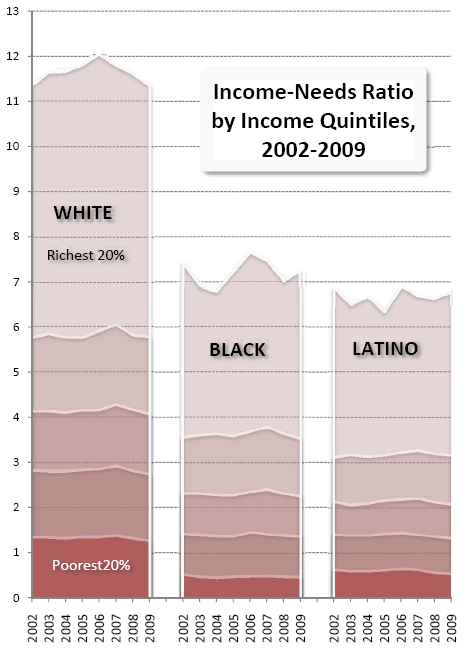

Yesterday I posted the news that the percent of Americans in poverty reached nearly 15% in 2009. Philip Cohen, at Family Inequality, used the same Census data to give us an idea of how both wealth and poverty are distributed across U.S. racial groups. We know that Blacks, Latinos, American Indians and some, but not all, Asian sub-groups are poorer, on average, than Whites. Cohen offers us a different way of looking at this, however, by plotting the income-to-needs ratio for Whites, Blacks, and Latinos over the last 8 years.

That income-need ratio is, by definition, 1.0 at the poverty line, and numbers above that are multiples of needs, so 3.0 is income of 3-times the poverty line.

That ratio sits along the vertical axis, with time at the horizontal:

This, Cohen explains, “…allows us to see the size of the White advantage…” He continues:

So, for example, the richest 5th of Whites are above 11-times the poverty line, while the poorest 5th of Whites are (on average) just above the poverty line. In contrast, the richest 5th of Blacks and Latinos are around 7-times the poverty line, and 40% of both groups are below 1.5-times the poverty line.

It’s not simply, then, that Blacks and Latinos are disproportionately poor. Their poor are also poorer than the poor Whites and their rich are less rich than rich Whites.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.