“It is fair to say,” writes historian Heather Williams about the Antebellum period in America, “that most white people had been so acculturated to view black people as different from them that they… barely noticed the pain that they experienced.”

“It is fair to say,” writes historian Heather Williams about the Antebellum period in America, “that most white people had been so acculturated to view black people as different from them that they… barely noticed the pain that they experienced.”

She describes, for example, a white woman who, while wrenching enslaved people from their families to found a distant plantation, describes them as “cheerful,” in “high spirits,” and “play[ful] like children.” It simply never occurred to her or many other white people that black people had the same emotions they did, as the reigning belief among whites was that they were incapable of any complex or deep feeling at all.

It must have created such cognitive dissonance, then — such confusion on the part of the white population — when after the end of slavery, black people tried desperately to reunite with their parents, cousins, aunties and uncles, nieces and nephews, spouses, lovers, children, and friends.

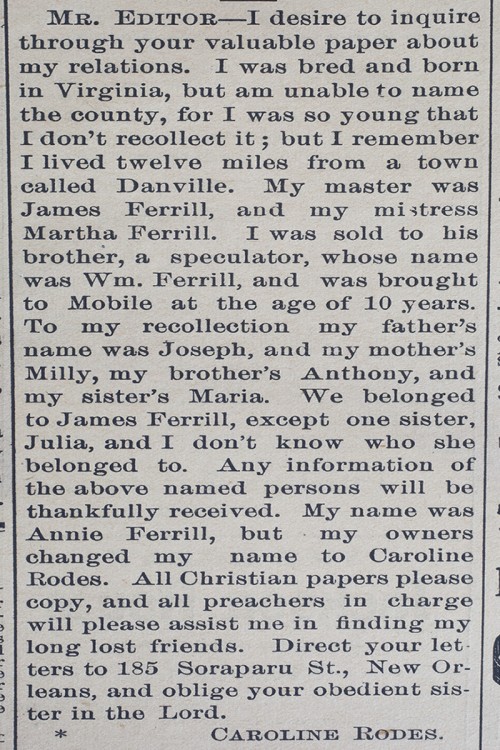

And try they did. For decades newly freed black people sought out their loved ones. One strategy was to put ads in the paper. The “Lost Friends” column was one such resource. It ran in the Southwestern Christian Advocate from 1879 until the early 1900s and a collection of those ads — more than 330 from just one year — has been released by the Historic New Orleans Collection. Here is an example:

The ads would have been a serious investment. They cost 50 cents which, at the time, would have been more than a day’s income for most recently freed people.

Williams reports that reunions were rare. She excerpted this success story from the Southwestern in her book, Help Me To Find My People, about enslaved families torn asunder, their desperate search for one another, and the rare stories of reunification.

A FAMILY RE-UNITED

In the SOUTHWESTERN of March 1st, we published in this column a letter from Charity Thompson, of Hawkins, Texas, making inquiry about her family. She last heard of them in Alabama years ago. The letter, as printed in the paper was read in the First church Houston, and as the reading proceeded a well-known member of the church — Mrs. Dibble — burst into tears and cried out “That is my sister and I have not seen her for thirty three years.” The mother is still living and in a few days the happy family will once more re-united.

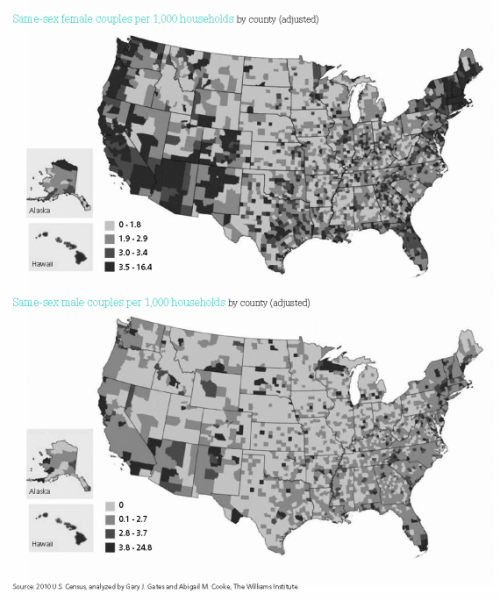

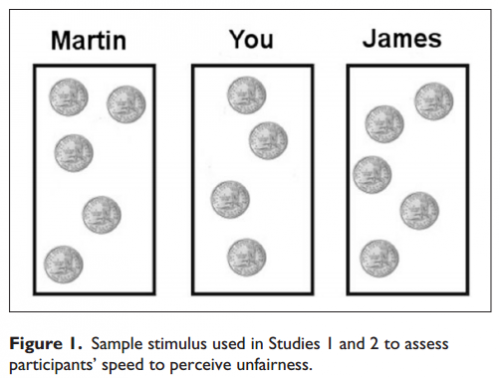

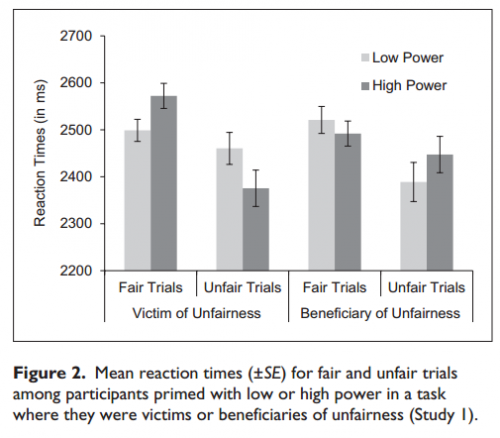

I worry that white America still does not see black people as their emotional equals. Psychologists continue to document what is now called a racial empathy gap, both blacks and whites show lesser empathy when they see darker-skinned people experiencing physical or emotional pain. When white people are reminded that black people are disproportionately imprisoned, for example, it increases their support for tougher policing and harsher sentencing. Black prisoners receive presidential pardons at much lower rates than whites. And we think that black people have a higher physical pain threshold than whites.

How many of us tolerate the systematic deprivation and oppression of black people in America today — a people whose families are being torn asunder by death and imprisonment — by simply failing to notice the depths of their pain?

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.