The phrase “service economy” — commonly used to describe the U.S. economic profile these days — refers to a decrease in manufacturing (where we make things for people) and an increase in the service sector (where we do stuff for people).

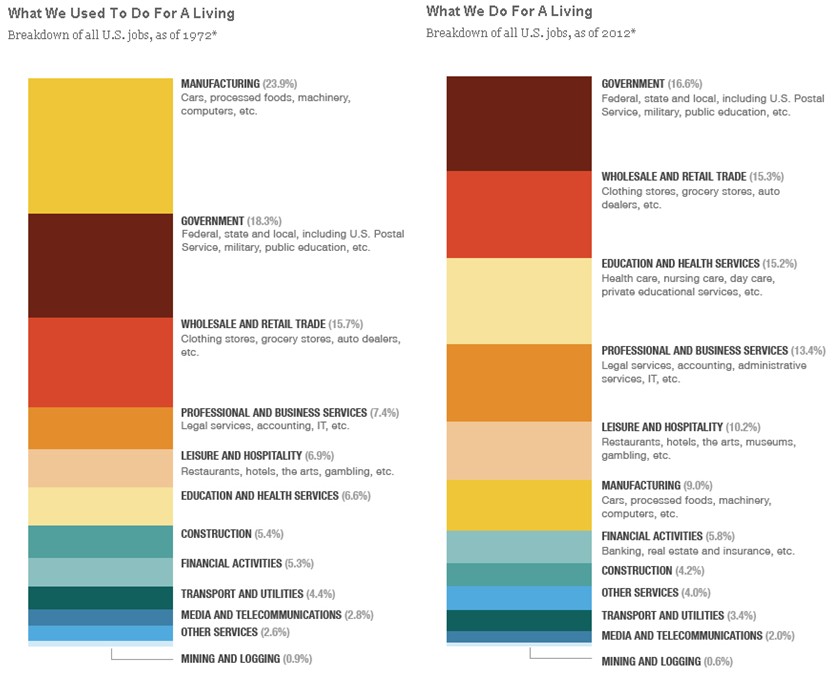

Planet Money put together stacked bar graphs to illustrate the increasing importance of service in our economy (1972 on the left, 2012 on the right). Manufacturing (making things) is in yellow, so you can clearly see its decline in prominence. Service sectors include “professional and business services,” “leisure and hospitality,” and “education and health services.”

So, when people talk about the move to a service economy, these are the changes they’re talking about. We also see the “servitization of products” (don’t you love academics?), or a tendency for products to come with more and more service. A restaurant, for example, offers a product (made by the chef), but also a degree of service (offered by the wait staff). Both the quality of the food and the service vary as you move from fast food restaurants to high end eateries. When we see a servitization of products, we see a ratcheting up of the level of expected service that attends any given product.

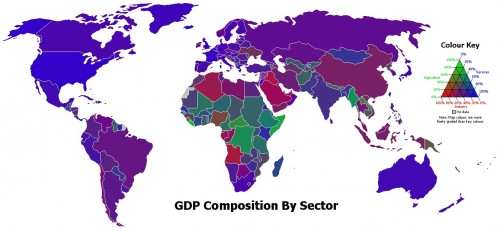

The U.S. economy, by the way, is more heavily characterized by service than most of the world. The map below is colored to indicate the relative balance between service (blue), manufacturing (red), and agricultural (green) industries in each state. You can see that the U.S. is among the bluest country on the map:

One of the concerns with the move to a service economy is that service jobs on the low end of the occupational hierarchy tend to be “bad” jobs, while manufacturing jobs, even when they’re on the low end, tend to be “good.” Service jobs are “bad” in the sense that they tend to have low wages, underemployment, little chance for advancement, and poor or no benefits. We’re talking, here, about jobs in sales, cashiering, food preparation, and the like. Because of this tendency, the move to a service economy is taking some of the blame for the shrinking of the middle class.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.