For the last week of December, we’re re-posting some of our favorite posts from 2011.

————————

It seems obvious that basic cognitive perceptions shouldn’t vary by society. That is, that our eyes should see, and our brains should process, essentially the same no matter what we call ourselves, what language we speak, or what holidays we observe. It turns out, however, that even basic cognitions vary across the world.

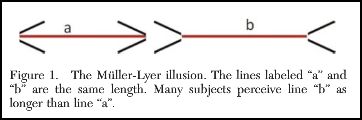

Most Americans, for example, perceive the two lines in this optical illusion to be of different lengths, with line a shorter than line b. In fact, they are the same length.

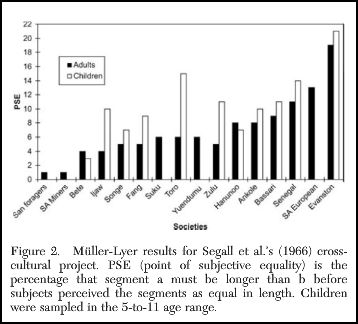

But, as argued by Joseph Henrich and colleagues in the Journal of Behavioral and Brain Sciences, our susceptibility to this illusion varies by culture. On average, line a needs to be another fifth longer than line b before the average American undergraduate evaluates the lines to be equal in length. Most other societies that have been tested on this illusion, however, require substantially less manipulation. The figure below compares how individuals in different societies perform on this test. The measures are tricky, and you can read more about them here; what you need to know for now is that the societies on the right are more susceptible to the illusion and the societies on the left less.

Observing that individuals in more developed societies (e.g., Evanston, Illinois) tend to be more vulnerable to the illusion — indeed, that in some societies, such as the San foragers of the Kalahari, it doesn’t qualify as an illusion at all — Henrich and his co-authors argue that exposure to “modern environments” may be the culprit:

…visual exposure during ontogeny to factors such as the “carpentered corners” of modern environments may favor certain optical calibrations and visual habits that create and perpetuate this illusion. That is, the visual system ontogenetically adapts to the presence of recurrent features in the local visual environment.

Even basic cognition, that is, varies across cultures.

As Henrich et al. argue, this calls into question all of the truisms of psychology based, primarily, on experimental research with Western subjects.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.