Sociologists spend a lot of time thinking about lives in social context: how the relationships and communities we live in shape the way we understand ourselves and move through the world. It can be tricky to start thinking about this, but one easy way to do it is to start collecting social facts. Start by asking, what’s weird about where you’re from?

I grew up on the western side of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan, so my eye naturally drifts to the Great Lakes every time I look at a map of the US. Lately I’ve been picking up on some interesting things I never knew about my old home state. First off, I didn’t realize that, relative to the rest of the country, this region is a hotspot for air pollution from Chicago and surrounding industrial areas.

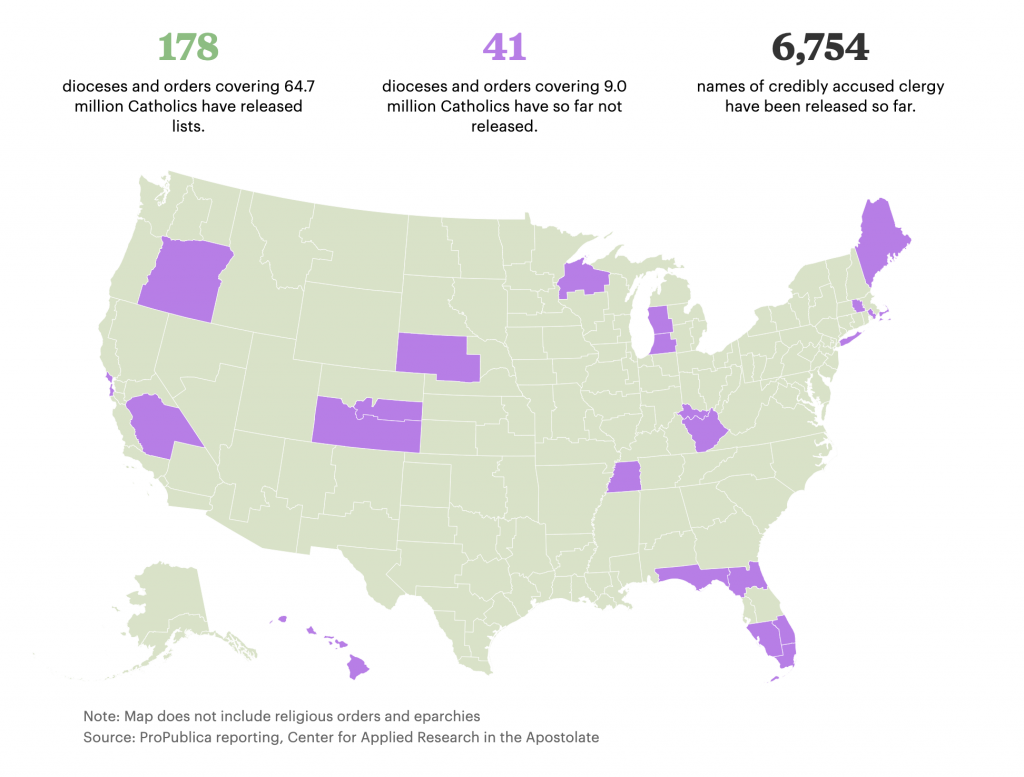

Second, I was looking at ProPublica’s reporting of a new database of Catholic clergy credibly accused of abuse, and noticed that the two dioceses covering western MI haven’t yet disclosed information about possible accusations. I didn’t grow up Catholic, but as a sociologist who studies religion it is weird to think about the institutional factors that might be keeping this information under wraps.

Third, there’s the general impact of this region on the political and cultural history of the moment. West Michigan happens to be the place that brought you some heavy hitters like Amway (which plays a role in one of my favorite sociological podcasts of last year), the founder of Academi (formally known as Blackwater), and our current Secretary of Education. In terms of elite political and economic networks, few regions have been as influential in current Republican party politics.

I think about these facts and wonder how much they shaped my own story. Would I have learned to like exercise more if I could have actually caught my breath during the mile run in gym class? Did I get into studying politics and religion because it was baked into all the institutions around me, even the business ventures? It’s hard to say for sure.

What’s weird about where YOU’RE from? Doing this exercise is great for two reasons. First, it helps to get students thinking in terms of the sociological imagination — connecting bigger social and historical factors to their individual experiences. Second, it also helps to highlight an important social research methods point about the ecological fallacy by getting us to think about all the ways that history and social context don’t necessarily force us to turn out a certain way. As more data become public and maps get easier to make, it is important to remember that population correlates with everything!

Evan Stewart is an assistant professor of sociology at University of Massachusetts Boston. You can follow his work at his website, or on BlueSky.

Botox has forever transformed the primordial battleground against aging. Since the FDA approved it for cosmetic use in 2002, eleven million Americans have used it. Over 90 percent of them are women.

Botox has forever transformed the primordial battleground against aging. Since the FDA approved it for cosmetic use in 2002, eleven million Americans have used it. Over 90 percent of them are women.