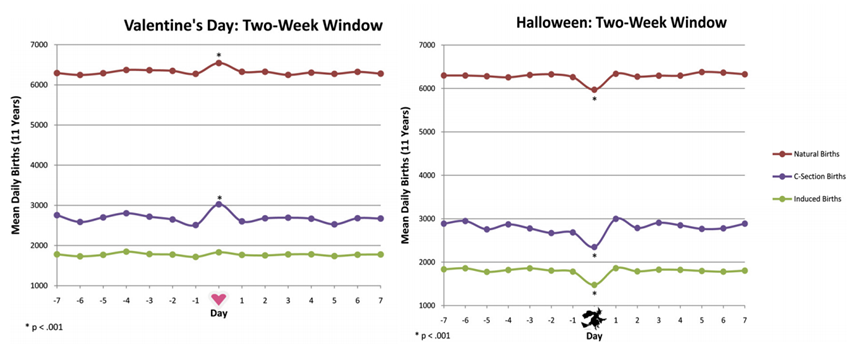

“Future research is needed to identify the process,” write the authors, but it appears that pregnant women have some control over when they give birth. A study of birth incidence on Halloween and Valentine’s Day, by public health scholar Becca Levy and colleagues, showed that spontaneous births dipped on the former and rose on the latter.

The authors suggest that this contributes to growing evidence that culture influences birth timing. Women’s bodies resist giving birth on a day associated with fright and death, but give into birth on a day associated with love. The authors recommend extra staffing on obstetric wards on Valentine’s Day and sending a few more doctors and nurses into the streets on Halloween.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.