For the last week of December, we’re re-posting some of our favorite posts from 2012. Originally cross-posted at Inequality by Interior Design.

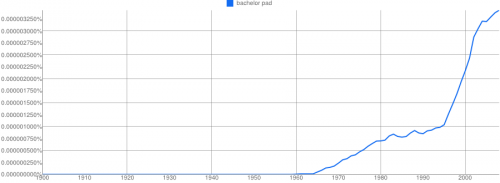

There is not actually a great deal of literature on “man caves,” “man dens,” and the like–save for some anthropological and archeological work using the term a bit differently. There is, however, a substantial body of literature dealing with bachelor pads. The “bachelor pad” is a term that emerged in the 1960s. It was a style of masculinizing domestic spaces heavily influenced by “gentlemen’s” magazines like Esquire and Playboy. Originally referred to as “bachelor apartments,” “bachelor pad” was coined in an article in the Chicago Tribune, and by 1964 it appeared in the New York Times and Playboy as well.

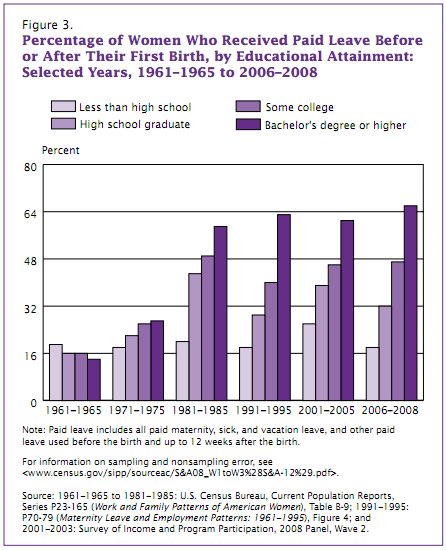

It’s somewhat ironic that the “bachelor pad” came into the American cultural consciousness at a time when the median age at first marriage was at a historic low (20.3 for women and 22.8 for men). So, the term came into usage at a time when heterosexual marriage was in vogue. Why then? Another ironic twist is that while the term has only become more popular since it was introduced, “bachelorette pad” never took off–despite the interesting finding that women live alone in larger numbers than do men. I think these two paradoxes substantiate a fundamental truth about the bachelor pad–it has always been more myth than reality (see here, here, here, here, and here).

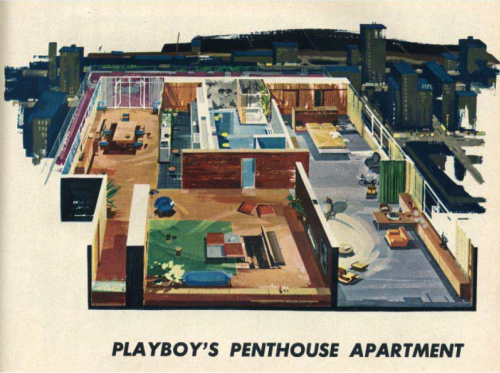

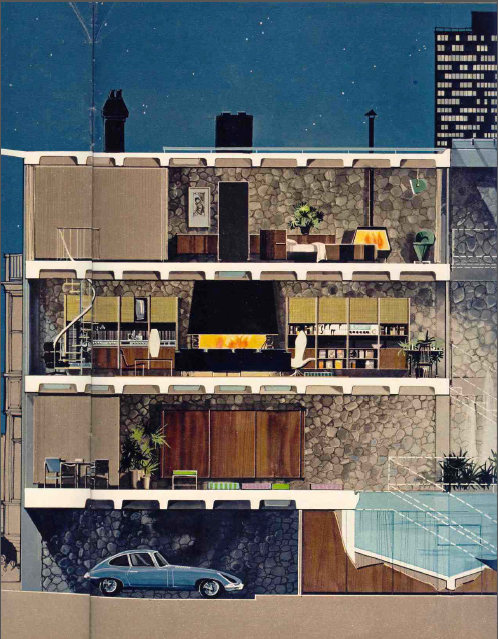

The gendering of domestic space had been a persistent dilemma since the spheres were separated in the first place. Few men were ever able to afford the lavish, futuristic and hedonistic “pads” advertised in Esquireand Playboy. But they did want to look at them in magazines.

A small body of literature on bachelor pads finds that they played a significant role in producing a new masculinity over the course of the 21st century. As Bill Ogersby puts it, “A place where men could luxuriate in a milieu of hedonistic pleasure, the bachelor pad was the spatial manifestation of a consuming masculine subject that became increasingly pervasive amid the consumer boom of the 1950s and 1960s” (here). The really interesting thing is that few men were actually able to luxuriate in these environments. Yet Playboy — along with a host of copycat magazines — spent a great deal of money, time, and effort perpetuating a lifestyle in which few men engaged. Indeed, outside of James Bond movies and the Playboy Mansion, I wonder how many actual bachelor pads exist or ever existed.

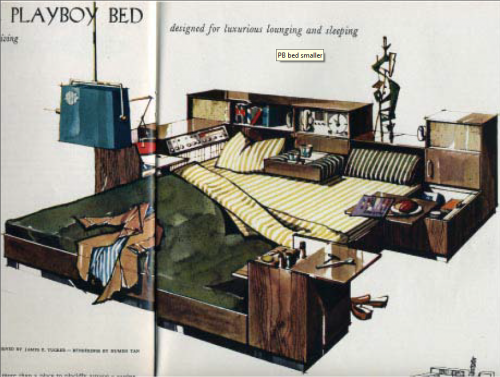

In the 1950s — despite a transition into consumer culture — consumption was regarded as a feminine practice and pursuit. Bachelor pads — and the magazines that sold the images of these domestic spaces to men around the country — helped men bridge this gap. More than a few have noted the importance of Playboy’s (hetero)sexual content in helping to sell consumption to American men. Barbara Ehrenreich said it this way: “The breasts and bottoms were necessary not just to sell the magazine, but to protect it” (here). Additionally, the masculinization of domestic space took many forms in early depictions of bachelor pads with ostentatious gadgetry of all types, beds with enough compartments and features to be comparable to Swiss Army knives, and each room designed in anticipation of heterosexual conquest at a moment’s notice.

Paradoxically, bachelor pads seem to have been produced to sell men thehistorically “feminized” activity of consumption.

I’m guessing that many of the “man caves” I’ll see in my research wouldn’t necessarily fit the image most of us conjure in our minds. But the ways men with caves talk about them are replete with images not yet fully realized by men who are most often economically incapable of architecturally articulating domestic spaces without which they may never feel “at home.”

———————

Tristan Bridges is a sociologist of gender and sexuality. He starts as an Assistant Professor of Sociology at the College at Brockport (SUNY) in the fall of 2012. He is currently studying heterosexual couples with “man caves” in their homes. Tristan blogs about some of this research and more at Inequality by (Interior) Design. You can follow him on twitter @tristanbphd.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.