Remember the hymen? The hymen is that flap of skin that “seals” the vagina until a woman has sexual intercourse for the first time. Supposedly one could tell whether a girl/woman was a virgin by whether her hymen was “intact.” (It bears repeating that neither of these things are true: it doesn’t “seal” the vagina and is not a sign of virginity at all.)

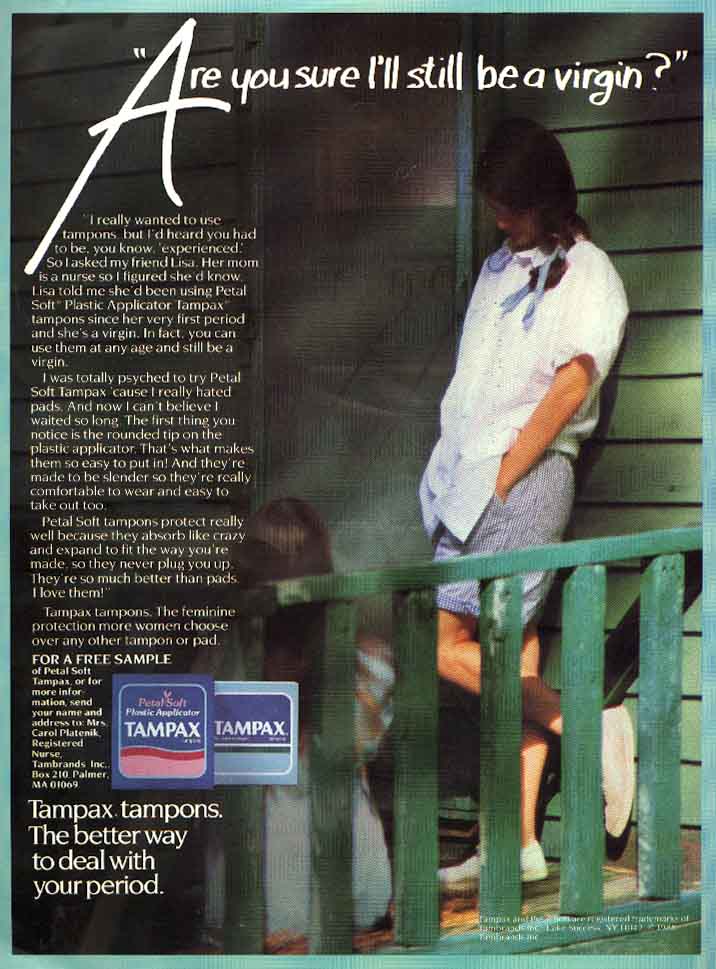

Because an intact hymen signaled virginity, and virginity has been considered very important, preserving and protecting the hymen was, at one time, an important task for girls and women. You can imagine how tricky this made the marketing of that brand new product: the tampon. Early marketing made an effort to dispel the idea that sticking just anything up there de-virginized you. It worked. (In fact, some partially credit tampon manufacturers for the de-fetishization of the hymen that’s occurred over the last 60 years.)

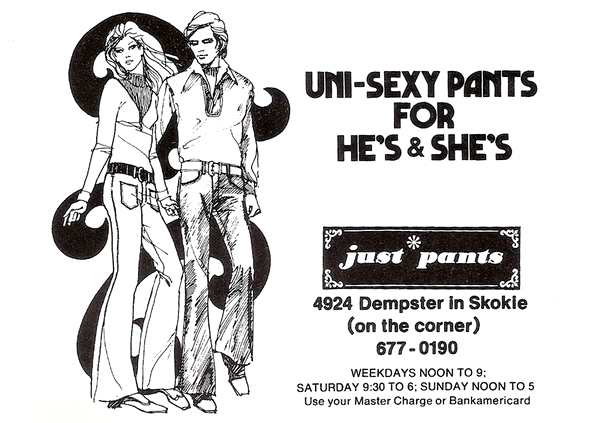

We still see tampon marketing addressing the question. Here’s a link to a website where it’s a FAQ and here’s an example of an advertisement from the ’70s ’90s:

Selected text:

I really wanted to use tampons, but I’d heard you had to be, you know, ‘experienced.’ So I asked my friend Lisa. Her mom is a nurse so I figured she’d know. Lisa told me she’d been using Petal Soft Plastic Applicator Tampax tampons since her very first period and she’s a virgin. In fact, you can use them at any age and still be a virgin.

See this post, too, on the marketing of tampon to women in the workforce (wearing pants!) during World War II.

—————————

Lisa Wade is a professor of sociology at Occidental College. You can follow her on Twitter and Facebook.