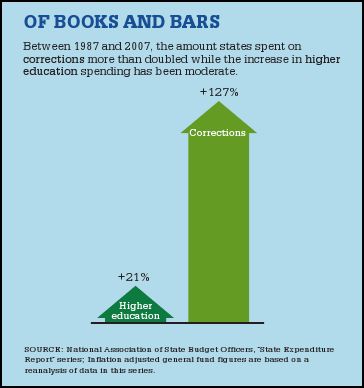

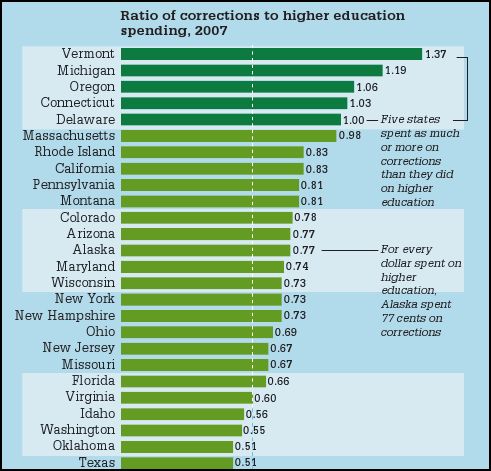

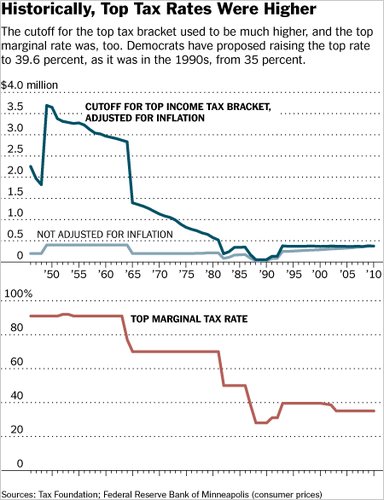

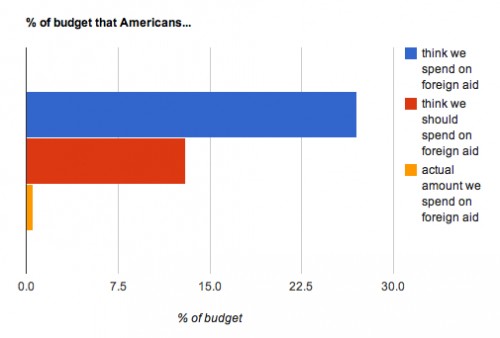

In an earlier post we reviewed research by epidemiologists Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett showing that income inequality contributes to a whole host of negative outcomes, including higher rates of mental illness, drug use, obesity, infant death, imprisonment, and interpersonal trust.

In the 3 1/2-minute video below, Kate Pickett argues that social inequality causes violence by creating status inequalities that those on the bottom respond to with violence.

Pickett and Wilkinson’s data is striking, but I’m not sure I buy that low status combined with status-sensitivity instigates violence. Sociologists have made this argument; but others have questioned these conclusions.

Villanova University’s Lance Hannon, for example, tested this “subculture of violence” thesis as applied to poor African Americans. Using police department homicide data, he found no evidence that Black people were more likely than White people to react to an insult with violence. This is swapping race for class, of course (and Hannon doesn’t control for class because the data was limited), but it does suggest that we should think carefully about the kind of argument Pickett is making.

See Dr. Pickett making similar arguments as to why raising the average national income in developed countries doesn’t make people happier or enable them to live longer and how status inequality increases stress. And see more about income inequality and national well-being at Equality Trust.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.