You may have heard the good news last week that Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that the U.S. unemployment rate dropped to 9.0% in January, combined with the somewhat conflicting news that payrolls increased by only 36,000 jobs. How is unemployment dropping without a significant increase in the number of people working?

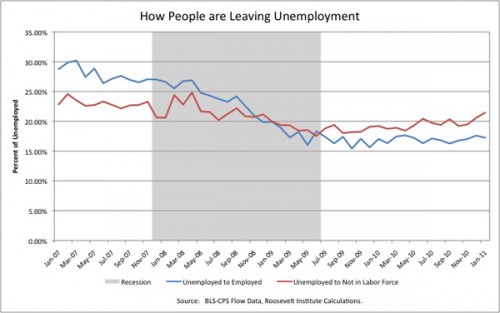

Talking Points Memo posted a graph that gives some insight, and it isn’t encouraging. The blue line shows the % of unemployed who stopped counting as unemployed because they found work. The red line, on the other hand, shows the % of unemployed workers who quit being unemployed because they have stopped looking for work, and thus are categorized as “not in the labor force” rather than unemployed. Currently, more of the drop in unemployment rates are due to people giving up on finding work rather than them finding jobs (via Rortybomb):

The Roosevelt Institute has a detailed report about trends in unemployment.

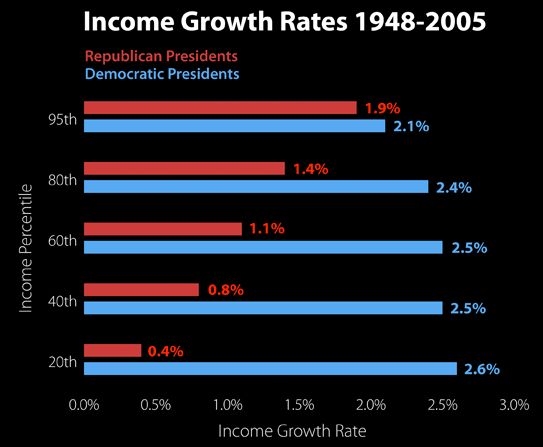

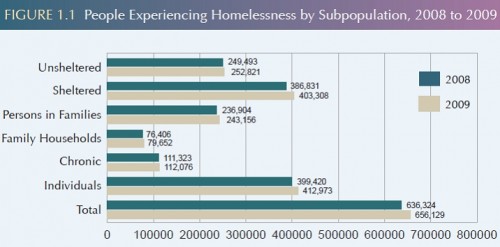

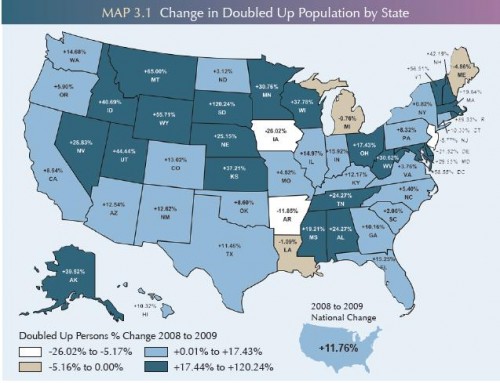

This pattern has significant long-term consequences, since a period of unemployment has serious negative effects on individuals’ income for years even after they do finally get jobs. This impacts not just individuals and their families, but entire communities, counties, and states, which suffer from the increased need for services, lowered productivity, and loss of tax revenue.