Cross-posted at Reports from the Economic Front.

How do corporations escape paying taxes? Businessweek recently ran a story on Google that helps to explain how they do it.

The story begins by noting that: “Google has made $11.1 billion overseas since 2007. It paid just 2.4 percent in taxes. And that’s legal.” This is pretty incredible because Google does business in many advanced capitalist countries with high tax rates. For example, “The corporate tax rate in the U.K., Google’s second-largest market after the U.S., is 28 percent.”

While the article focuses on Google, and how it avoids paying taxes, it made clear that most of the leading high-technology companies use remarkably similar techniques to achieve similar results.

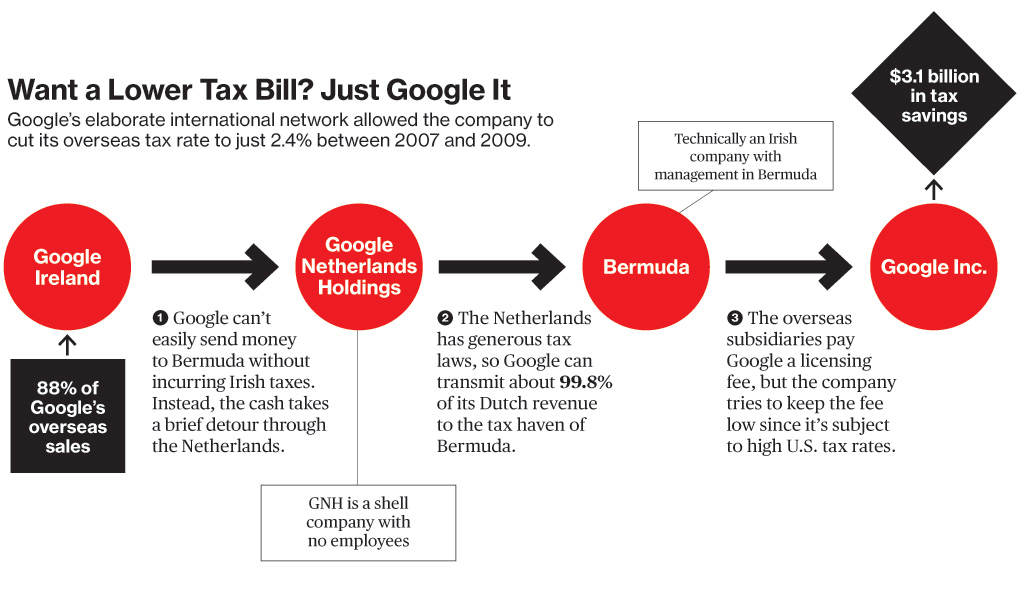

Ok, so how does Google do it? Google’s office in Ireland is the center of the company’s international operations. In 2009 it “was credited with 88 percent of the search juggernaut’s $12.5 billion in sales outside the U.S.” But Google doesn’t pay taxes on that amount, because most of the profits went to Bermuda, where there is no corporate income tax.

So, how did Google get its profits to Bermuda? Businessweek explains:

Google’s profits travel to the island’s white sands via a convoluted route known to tax lawyers as the “Double Irish” and the “Dutch Sandwich.” In Google’s case, it generally works like this: When a company in Europe, the Middle East, or Africa purchases a search ad through Google, it sends the money to Google Ireland. The Irish government taxes corporate profits at 12.5 percent, but Google mostly escapes that tax because its earnings don’t stay in the Dublin office, which reported a pretax profit of less than 1 percent of revenues in 2008.

Irish law makes it difficult for Google to send the money directly to Bermuda without incurring a large tax hit, so the payment makes a brief detour through the Netherlands, since Ireland doesn’t tax certain payments to companies in other European Union states. Once the money is in the Netherlands, Google can take advantage of generous Dutch tax laws. Its subsidiary there, Google Netherlands Holdings, is just a shell (it has no employees) and passes on about 99.8 percent of what it collects to Bermuda. (The subsidiary managed in Bermuda is technically an Irish company, hence the “Double Irish” nickname.)

This set-up (as Businessweek describes it) also helps Google lower its tax bill in the U.S. Google Ireland licenses its search and advertizing technology from Google’s headquarters in Mountain View, California. Obviously this technology is worth a lot—but Google headquarters keeps the licensing fee to Google Ireland low. Doing so means that Google headquarters can minimize its U.S. earnings and thus its tax obligations to the U.S. government. And of course, Google Ireland knows how to move its profits around to minimize its tax liabilities.

Not surprisingly, corporations are always eager to learn from each other. Thus, “Facebook is preparing a structure similar to Google’s that will send earnings from Ireland to the Cayman Islands, according to company filings and a person familiar with the arrangement.” Microsoft already has one in place.

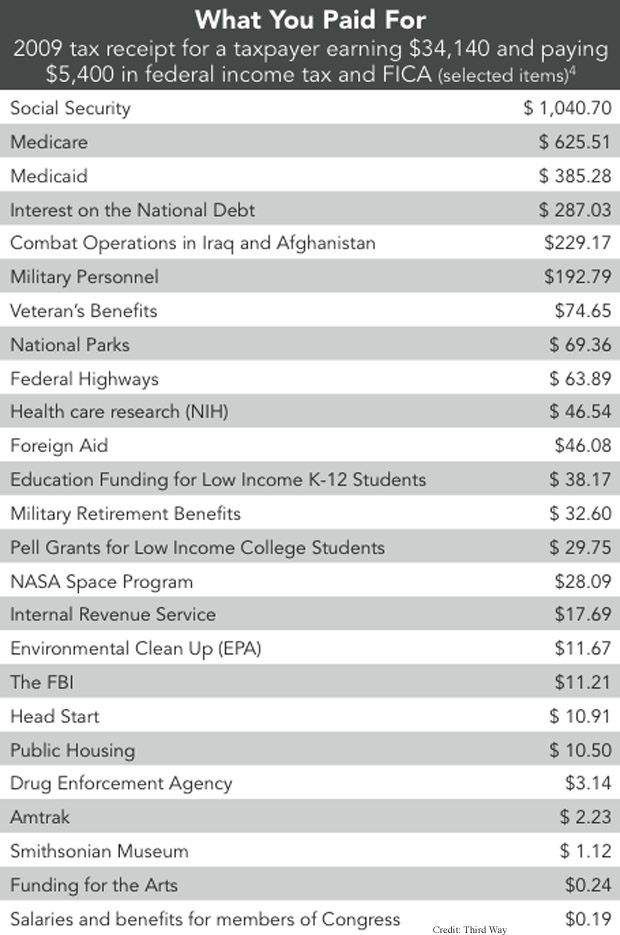

According to one study cited by Businessweek (done by Kimberly A Clausing, an economics professor at Reed College), these kinds of profit shifting arrangements cost the U.S. government as much as $60 billion a year. And of course Ireland also loses plenty. Too bad that the governments of Ireland and the U.S. are suffering from large federal deficits and under immense pressure to slash spending. Collateral damage I guess to the profit-making drive.

What is being done to change this apparently legal racket? According to Businessweek:

The government has made halting steps to change the rules that let multinationals shift income overseas. In 2009 the Treasury Dept. proposed levying taxes on certain payments between U.S. companies’ foreign subsidiaries, potentially including Google’s transfers from Ireland to Bermuda. The idea was dropped after Congress and Treasury officials were lobbied by companies including General Electric, Hewlett-Packard, and Starbucks, according to federal disclosures compiled by the nonprofit Center for Responsive Politics. In February the Obama Administration proposed measures to curb companies’ ability to shift profits offshore, but they’ve largely stalled.

A nice cozy system, isn’t it.