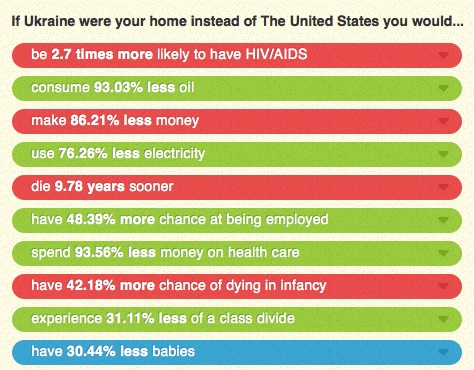

Dmitriy T.M. sent in this hilarious 2-minute rap about first world problems. The idea is to draw attention to how the daily frustrations faced by those of us in the most advantaged and developed countries in the world are really, really, like really small.

Edit: Sociologist Michael Kimmel reminds me that, though in certain ways the above is definitely true, it’s also not useful to trivialize the ways in which advantaged and developed countries still create suffering. Some of us benefit from our overall advantage more than others.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.