Marriage–as a social and legal institution–has not always been what it is today.

In early American history, when families largely lived on farms and worked for sustenance, people didn’t marry because they loved each other. And they certainly didn’t split up because they did not. Marriage choices were highly influenced by their families and, once married, husbands and wives formed a working partnership aimed at production. They teamed up to support themselves and make children who would take care of them when they were old and help them in the meantime.

Today, we still (generally) think of marriage as comprised of a man, a woman, and kids, but mutual love and happiness are now central goals of marriage. This idea only emerged in the 1900s. It hasn’t actually been around all that long.

I bring this up in order to shed some light on the pro- and anti- gay marriage rhetoric.

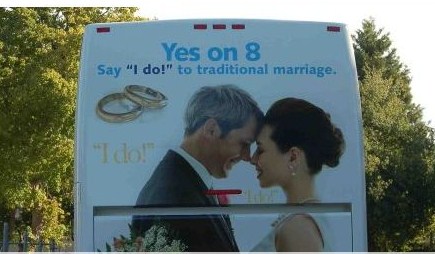

On the one hand, those against gay marriage need to define “marriage” in a way that excludes same-sex couples. One way to do this is to refer to a “traditional” marriage (image found here).

But there is no such thing as a “traditional” marriage, just a long history of evolving forms of marriage. For example, few anti-gay marriage types would actually be in favor of returning marriage to one in which women were property that can’t contract, vote, testify in court, own anything, and have no rights to their own bodies or custody of their children (though the idea that women are property is still out there today). Because there is no such thing as a “traditional” marriage (that is, no reason to privilege one historical form over another), when someone speaks of “traditional” marriage, they actually just mean “the kind of marriage that I like that I am pretending existed throughout all time before this current threat right now.”

On the other hand, to make an argument in favor of gay marriage rights, the movement must either (1) change the collective agreement as to what marriage is (the social construction of marriage) or (2) convince the collective that gay marriage already is what we believe marriage to be.

This ad in favor of gay marriage does the latter. Mobilizing the social construction of marriage as about love, the commercial then defines same-sex relationships as about love. If you accept both premises, then, presto, you are pro-gay marriage. That is exactly what this commercial is trying to do:

NEW! This Swedish commercial for Bjorn Borg’s dating website, sent in by Ed L., similarly mobilizes the idea that marriage is for love and that gay men’s marriages are, therefore, beautiful: