Since its release in November, Get Up!’s commercial supporting gay marriage in Australia has garnered substantial social media interest (over four million views on Youtube). The U.S. LGBT news magazine The Advocate called it “possibly the most beautiful ad for marriage equality we’ve seen” (source). Take a look:

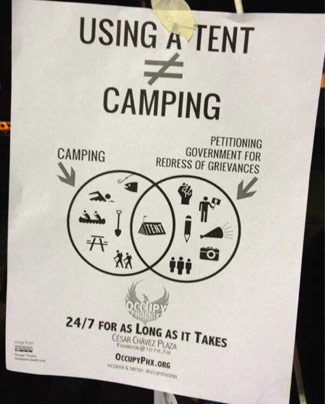

From a sociological point of view, what is interesting about this ad is how it avoids the powerful, but charged language of equality and rights. Supporters of same-sex marriage typically frame their cause in terms of non-discrimination (“all people are equal”), non-interference or privacy (“how is my gay marriage affecting yours?”) or in terms of freedom of speech (“I should marry who I want”). See images of posters using this frame here and here.

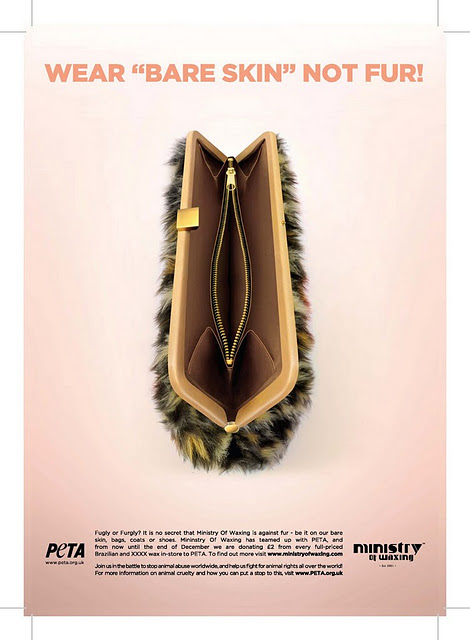

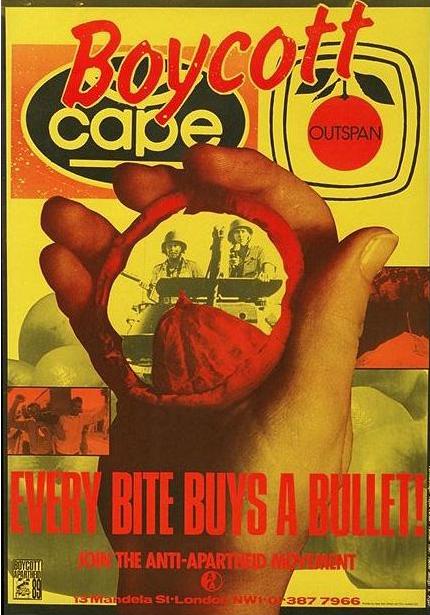

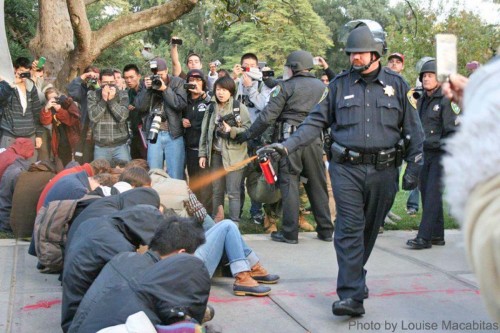

Rights language such as this, however, comes with the potential of conflicts and trade-offs. Accordingly, opponents of same-sex marriage have often capitalized on this in their responses. This poster, for instance, expresses a fear or mockery of assertive, unbridled individualism. Posters with this frame here.

This “Yes to Proposition 8” video is another good example. In it one woman claims that, if gay marriage is legal, her religious identity will be subject to discrimination and her freedom to speech will be contested.

The language used by the marriage equality movement, then, enables its opponents to re-frame their responses in the same type of language.

This is why the Get Up! commercial is a game changer. Instead of using “rights talk,” it keeps both words and slogans to a minimum. It uses visuals to embed the couple in a network of family and friends. At the end, for example, the camera steps back to show not just the couple but a wider network of people who happily witness a marriage proposal. This approach implicates the happiness of not just two individuals, but a community. The message is that gay marriage is not just about individual rights, but about collective celebration and social recognition.

—————————

Ridhi Kashyap is a researcher in the Migration Group at the Institute for Empirical and Applied Sociology in Bremen, Germany. She studied interdisciplinary social sciences at Harvard University, and was a human rights fellow there after graduating in 2010. She is actively interested in human rights, particularly as they implicate issues of gender, migration, and development.

If you would like to write a post for Sociological Images, please see our Guidelines for Guest Bloggers.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.