Sociologists

studying emotion have opened up the inner, private feelings of anger, fear,

shame, and love to reveal the far-reaching effects of social forces on our most

personal experiences. This subfield has given us new words to make sense of shared

experiences: emotional labor in our professional lives, collective

effervescence at sporting events and concerts, emotional capital as a resource

linked to gender, race, and class, and the relevance of power in shaping

positive and negative emotions.

Despite

these advances, scholars studying emotion still struggle to capture emotion

directly. In the lab, we can elicit certain emotions, but by removing context,

we remove much of what shapes real-life experiences. In surveys and interviews,

we can ask about emotions retrospectively, but rarely in the moment and in

situ.

One

way to try to capture emotions as they unfold in all of their messy glory is

through audio diaries (Theodosius 2008). Our team set out to use audio

diaries as a way to understand the emotions of hospital nurses—workers on the

front lines of healthcare. We asked nurses to make a minimum of one recording

after each of 6 consecutive shifts. Some made short 10-minute recordings. Some

talked for hours in the midst of beeping hospital machines and in break rooms,

while walking to their cars, driving home, and as they unplugged after a long

day. With the recorders out in the world, we couldn’t control what they

discussed. We couldn’t follow-up with probing questions or ask them to move to

a quieter location to minimize background noise.

But what this lack of control gave us was a trove of emotions and reflections, experienced and processed while recording. One fruitful way to try to distill these data, we found, was through visuals. We created wavelength visualizations in order to augment our interpretation of diary transcripts. Pairing the two reintroduces some of the ‘texture’ of spoken word often lost in the transcription process (Smart 2009:296). The following is from our new article in the journal, Qualitative Research (Cottingham and Erickson Forthcoming).

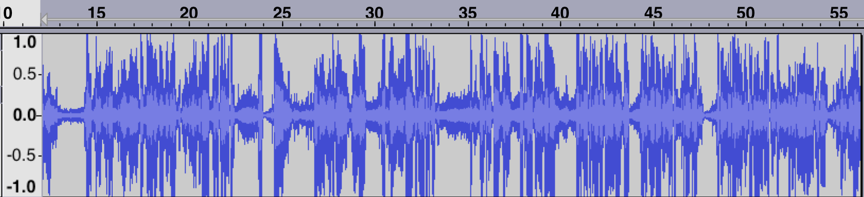

In this first segment, Tamara (all participant names are pseudonyms) describes a memorable situation in which a patient’s visitor assumed that Tamara was a lower-level nursing aid rather than a registered nurse (the full event is discussed in greater detail in Cottingham, Johnson, and Erickson 2018). This caused her to feel “ticked” (angry), which is the word she uses after a quick, high-pitched laugh that peaks the wavelength just after the 30-s mark (Figure 1). The wavelength peak just after the 1:15 mark is as she says the word ‘why’ with notable agitation in ‘I’m not sure why. Maybe cuz I’m Black. I don’t know.’

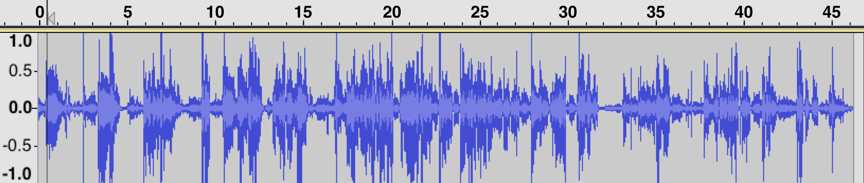

We can compare Figure 1 that visualizes Tamara’s feelings of

anger with the visualization of emotion in Figure 2. “Draining” is the

description Tamara gives at the beginning of this second segment. The peak just

after the 15-second mark is from a breathy laugh as she describes her sister “who

has MS is sitting on the bedside commode” when she gets home from work. After

the 45-second mark, she has a similar breathy laugh but in conjunction with the

word ‘compassionate’ as she says ‘I’m trying to be as empathetic and

compassionate as I want to be, but I know I’m really not. So I feel kinda

crappy, guilty maybe about that.’ Just before the 1:30 mark she draws out the

words ‘draining’ and ‘frustrating’ before finishing: ‘because you leave it and

you come home to it…you know…yeah.’ We can see that the segment ends with

longer pauses, muted remarks, and sighs, suggesting low energy and representing

the drained feelings she expresses, particularly in comparison to the lively

energy seen in the first segment when she discusses feeling angry.

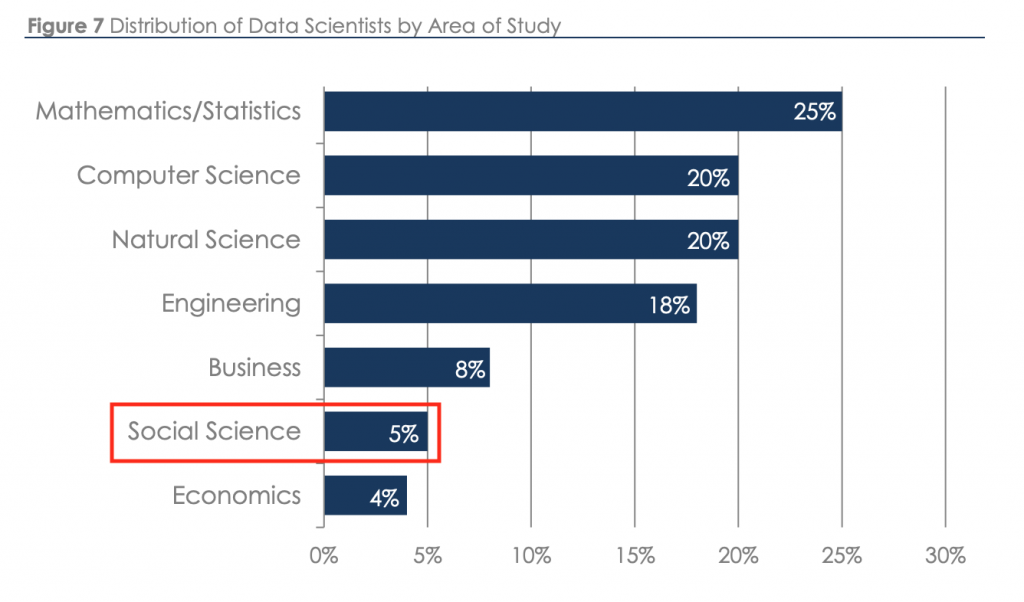

A second example comes from Leah, recorded while driving to work. Here she is angry (“pissed off”) because she has to work on a day that she was not originally scheduled to work. This segment is visualized in the waveform shown in Figure 3.

In contrast to her discussion of being pissed off and working to ‘retain enough righteous indignation’ to confront her boss later (in figure 3), we see a different wavelength visualization in her second segment (figure 4). In that segment, she describes her lack of enthusiasm for continuing the shift. She reflects on this lack of desire (‘I don’t want to stay’) by stepping outside her own feelings and contrasting them with the dire circumstances of her young patient. This reflexivity leads her to conclude that she has reached the limits of her ability to be compassionate.

To

be sure, waveform visualizations are only meaningful in tandem with what our nurses say. And they do not

provide definitive proof of certain emotions over others. They can’t fully

identify the sighs, deep inhales, uses of sarcasm, or other subtle features of

spoken diary entries. They do, however, offer some insight into how speed,

pitch, and pauses correspond to different emotional expressions and, arguably,

levels of emotional energy (Collins 2004) that vary across time and interactions.

While

there is little that can serve as a substitute for hearing the recordings

directly, the need to protect participants’ confidentiality compels us to turn

to other means to convey the nuances of these verbalizations. Visualization of

wavelengths, in combination with transcripts, can lend themselves to further

qualitative interpretation of these subtleties, conveying the dynamics of a

segment to others who do not have direct access to the recordings themselves.

Check

out the full, open-access article on this topic here and more on the experiences of nurses

here.

Marci Cottingham is assistant professor of sociology at the University of Amsterdam. She researches emotion and inequality broadly and their connection to healthcare and biomedical risk. She is a 2019-2020 visiting fellow at the HWK Institute for Advanced Study. More on her research can be found here: www.uva.nl/profile/m.d.cottingham

References:

Collins, Randall.

2004. Interaction Ritual Chains. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton

University Press.

Cottingham,

Marci D. and Rebecca J. Erickson. Forthcoming. “Capturing Emotion with Audio

Diaries.” Qualitative Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794119885037

Cottingham,

Marci D., Austin H. Johnson, and Rebecca J. Erickson. 2018. “‘I Can Never Be

Too Comfortable’: Race, Gender, and Emotion at the Hospital Bedside.” Qualitative

Health Research 28(1):145–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317737980

Smart,

Carol. 2009. “Shifting Horizons: Reflections on Qualitative Methods.” Feminist

Theory 10(3):295–308.

Theodosius,

Catherine. 2008. Emotional Labour in Health Care: The Unmanaged Heart of

Nursing. NY: Routledge.

[

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/49994069/Screen_Shot_2016-06-30_at_10.05.58_AM.0.0.png)