Sociologists studying emotion have opened up the inner, private feelings of anger, fear, shame, and love to reveal the far-reaching effects of social forces on our most personal experiences. This subfield has given us new words to make sense of shared experiences: emotional labor in our professional lives, collective effervescence at sporting events and concerts, emotional capital as a resource linked to gender, race, and class, and the relevance of power in shaping positive and negative emotions.

Despite these advances, scholars studying emotion still struggle to capture emotion directly. In the lab, we can elicit certain emotions, but by removing context, we remove much of what shapes real-life experiences. In surveys and interviews, we can ask about emotions retrospectively, but rarely in the moment and in situ.

One way to try to capture emotions as they unfold in all of their messy glory is through audio diaries (Theodosius 2008). Our team set out to use audio diaries as a way to understand the emotions of hospital nurses—workers on the front lines of healthcare. We asked nurses to make a minimum of one recording after each of 6 consecutive shifts. Some made short 10-minute recordings. Some talked for hours in the midst of beeping hospital machines and in break rooms, while walking to their cars, driving home, and as they unplugged after a long day. With the recorders out in the world, we couldn’t control what they discussed. We couldn’t follow-up with probing questions or ask them to move to a quieter location to minimize background noise.

But what this lack of control gave us was a trove of emotions and reflections, experienced and processed while recording. One fruitful way to try to distill these data, we found, was through visuals. We created wavelength visualizations in order to augment our interpretation of diary transcripts. Pairing the two reintroduces some of the ‘texture’ of spoken word often lost in the transcription process (Smart 2009:296). The following is from our new article in the journal, Qualitative Research (Cottingham and Erickson Forthcoming).

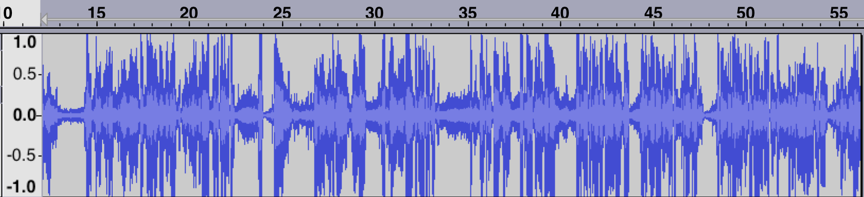

In this first segment, Tamara (all participant names are pseudonyms) describes a memorable situation in which a patient’s visitor assumed that Tamara was a lower-level nursing aid rather than a registered nurse (the full event is discussed in greater detail in Cottingham, Johnson, and Erickson 2018). This caused her to feel “ticked” (angry), which is the word she uses after a quick, high-pitched laugh that peaks the wavelength just after the 30-s mark (Figure 1). The wavelength peak just after the 1:15 mark is as she says the word ‘why’ with notable agitation in ‘I’m not sure why. Maybe cuz I’m Black. I don’t know.’

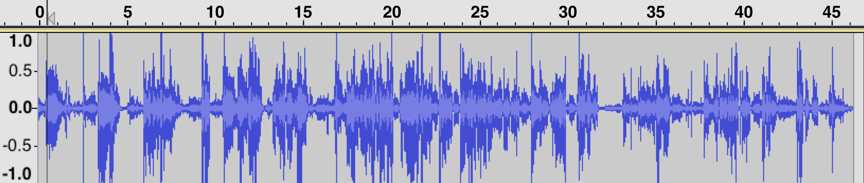

We can compare Figure 1 that visualizes Tamara’s feelings of anger with the visualization of emotion in Figure 2. “Draining” is the description Tamara gives at the beginning of this second segment. The peak just after the 15-second mark is from a breathy laugh as she describes her sister “who has MS is sitting on the bedside commode” when she gets home from work. After the 45-second mark, she has a similar breathy laugh but in conjunction with the word ‘compassionate’ as she says ‘I’m trying to be as empathetic and compassionate as I want to be, but I know I’m really not. So I feel kinda crappy, guilty maybe about that.’ Just before the 1:30 mark she draws out the words ‘draining’ and ‘frustrating’ before finishing: ‘because you leave it and you come home to it…you know…yeah.’ We can see that the segment ends with longer pauses, muted remarks, and sighs, suggesting low energy and representing the drained feelings she expresses, particularly in comparison to the lively energy seen in the first segment when she discusses feeling angry.

A second example comes from Leah, recorded while driving to work. Here she is angry (“pissed off”) because she has to work on a day that she was not originally scheduled to work. This segment is visualized in the waveform shown in Figure 3.

In contrast to her discussion of being pissed off and working to ‘retain enough righteous indignation’ to confront her boss later (in figure 3), we see a different wavelength visualization in her second segment (figure 4). In that segment, she describes her lack of enthusiasm for continuing the shift. She reflects on this lack of desire (‘I don’t want to stay’) by stepping outside her own feelings and contrasting them with the dire circumstances of her young patient. This reflexivity leads her to conclude that she has reached the limits of her ability to be compassionate.

To be sure, waveform visualizations are only meaningful in tandem with what our nurses say. And they do not provide definitive proof of certain emotions over others. They can’t fully identify the sighs, deep inhales, uses of sarcasm, or other subtle features of spoken diary entries. They do, however, offer some insight into how speed, pitch, and pauses correspond to different emotional expressions and, arguably, levels of emotional energy (Collins 2004) that vary across time and interactions.

While there is little that can serve as a substitute for hearing the recordings directly, the need to protect participants’ confidentiality compels us to turn to other means to convey the nuances of these verbalizations. Visualization of wavelengths, in combination with transcripts, can lend themselves to further qualitative interpretation of these subtleties, conveying the dynamics of a segment to others who do not have direct access to the recordings themselves.

Check out the full, open-access article on this topic here and more on the experiences of nurses here.

Marci Cottingham is assistant professor of sociology at the University of Amsterdam. She researches emotion and inequality broadly and their connection to healthcare and biomedical risk. She is a 2019-2020 visiting fellow at the HWK Institute for Advanced Study. More on her research can be found here: www.uva.nl/profile/m.d.cottingham

References:

Collins, Randall. 2004. Interaction Ritual Chains. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Cottingham, Marci D. and Rebecca J. Erickson. Forthcoming. “Capturing Emotion with Audio Diaries.” Qualitative Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794119885037

Cottingham, Marci D., Austin H. Johnson, and Rebecca J. Erickson. 2018. “‘I Can Never Be Too Comfortable’: Race, Gender, and Emotion at the Hospital Bedside.” Qualitative Health Research 28(1):145–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317737980

Smart, Carol. 2009. “Shifting Horizons: Reflections on Qualitative Methods.” Feminist Theory 10(3):295–308.

Theodosius,

Catherine. 2008. Emotional Labour in Health Care: The Unmanaged Heart of

Nursing. NY: Routledge.

[

Comments 52

Maryann — November 29, 2019

What nice research! Thanks for sharing! It was very interesting to read! And the visualization is great!

math homework — December 10, 2019

It is not a secret that not everyone can easily solve different math problems easily. But you can always get some assistance from the expert services that can complete your math homework.

https://grademiners.com — December 17, 2019

If you do not know how to write the proper multiple questions for your project, you can visit this link https://grademiners.com to get instant help from the expert services.

ewriters.pro — December 17, 2019

Visit the website of the expert online writing and editing services https://ewriters.pro/ to get the ability to ask the best online writers to write your professional academic paper.

ewriters.pro — December 17, 2019

Visit the website of the expert online writing and editing services ewriters.pro to get the ability to ask the best online writers to write your professional academic paper.

Sameb — January 22, 2020

Nova TV is a brand video streaming app that provides movies and TV shows.

avinash — February 5, 2020

Codm gfx is the best tool for hack pubg and other game have a fun!

avinash — February 5, 2020

tubemate 3.2.14 Best app for download youtube video free.

coca — February 13, 2020

I have read and read a lot of your posts, great, your article has a good and very useful content, thank you for sharing.

vex 3

writing online — February 21, 2020

very important article! Thanks. If you want to know how to express your emotions through writing feel free to visit htts://1ws.com

Alicia — February 21, 2020

very important article! Thanks. If you want to know how to express your emotions through writing feel free to visit writing online

avinash — February 26, 2020

Create and fun with byte

download now make vine videos and short videos

sonam — February 26, 2020

Create and fun with byte app

download now make vine videos and short videos

avinash — February 26, 2020

Create and fun with byte vine 2

download now make vine videos and short videos

Mosedince — February 27, 2020

I would suggest you visit this websitehttps://grandwriters.net/buy-coursework-online. I was looking for some help.

justlearn — March 4, 2020

Amazing to read about this delicious recipe! You always choose a mouth watering recipes like this hot chocolate with white peppermint. I love chocolate recipes thats'why I choose your site to read about it and now I've check more at https://grandwriters.net/assignment-editing-service which I'm able to manage my college thesis task.

Suman — March 5, 2020

I really appreciate this piece of content. Also, see more amazing content like this Easter Instagram Captions

ONE PIECE — July 11, 2020

ONE PIECE TREASURE CRUISE Apk Mod https://apkmodmenu.com/one-piece-treasure-cruise-apk-mod/

Ashley Ridley — August 13, 2020

Studying of emotion is a very interesting thing for me. Actually I want to be a Sociologists but due to my family pressure, I'm a developer now :D This is a funny thing but its true. In this time of the pandemic, emotions can be disturbed due to lock down and everybody is at home. You to chill your mind you should do some mind-blowing. I have an idea and this is the playing of smartphone games and doing home exercises. You can get best free exercise apps for android and enjoy it.

kjwoij — October 30, 2020

How to get a carsforcancer to get some help at the time when i need to visit a doctor for my therapies

Jenny — December 4, 2020

Nice Share!!

Thanks for sharing this useful information and it's worth taking online writing help if you get stuck with any of your assignments or project.

Jenny — December 4, 2020

Nice Share!!

Thanks for sharing this useful information and it's worth taking online writing help from here https://www.cheapestessay.com/ if you get stuck with any of your assignments or project.

Kries — January 26, 2021

Thx my friend!

Anonymous — January 28, 2021

In contrast to her discussion of being pissed off and working to ‘retain enough righteous indignation’ to confront her boss later (in figure 3), we see a different wavelength visualization in her second segment . https://hashalot.io/blog/kalkulyatory-majninga-raschet-pribylnosti-i-okupaemosti-majninga-na-asik-ah-i-videokartah/

Anonymous — January 28, 2021

She reflects on this lack of desire (‘I don’t want to stay’) by stepping outside her own feelings and contrasting them with the dire circumstances of her young patient. This reflexivity leads her to conclude that she has reached the limits of her ability to be compassionate. https://cryptograph.life/kripto-slovar/darknet-darknet-chto-eto-kak-tuda-popast-populyarnye-sayty

alex012 — May 24, 2021

DigitalAkki is best Digital Marketing Agency in Salt Lake City Providing complete Digital Marketing Service in Salt Lake City. If you are looking for Best Digital Marketing Agency in Salt Lake City, No doubt DigitalAkki is best option for you.

Read More

The 5 Best Spy Apps for iOS and Android — June 2, 2021

The 5 Best Spy Apps for iOS and Android in 2021 which can help you to hack enyone you need. I use these apps for a long time and i definitely recommend them for all who want to defend their phone or to check their friends.

Alex012 — June 4, 2021

If you want to learn Digital Marketing and searching for Digital Marketing Course in Chandigarh, you are in the right place. In today’s time, digital marketing is a trendy medium to scale and growth for your career. In this digital marketing course, we give you complete practical training, which provides you with an understanding of working with companies.

Digital Marketing Training,Online Marketing Course

sam012 — June 7, 2021

The Bespoke Group of Entrepreneurs (Bespoke-G-Ent) is a community of like-minded people that interact over startups, networking and trends. Our products are there to serve the needs that an every day entrepreneur may incur. Be it networking, style, productivity or health. We also have an eco-friendly selection.

Bespoke community

sfgcqh012 — June 18, 2021

Locksmith in 77433 – Economical and fast Locksmith professional Service in Cypress,

If you are looking for the best Locksmith in Cypress 77433, Magnet Locksmith is a very good option for you. We Offer excellent and Fast 24/7 locksmith Alternatives Anyplace in Cypress, Texas Region such as Lock Repair, Lockout service, Lock rekey, Office/home/car cupboard locks installation, fixing auto ignition, and all sorts of commercial, non-commercial and automotive locksmith specialist services, modifying the mix of lock, opening the doors, key substitution.

locksmith 77095

Locksmith in 77433

Samuel Wellington — June 25, 2021

Oh great!

https://www.google.com.

Tiffany Walls — June 25, 2021

wow!

google

Alex00 — July 14, 2021

MyInterityCab is your perfect travel partner if you need to hire a car. Our cab rental services range from outstation cabs to airport taxis. Call us to avail affordable one way and round trip offers. Our team is available 24 hours a day before, during and after the car rental takes place, just make your rental experience as smooth as possible.

one way cab

williamwo — August 3, 2021

All I need to unwind a bit is some legitimate flirting. Is this too much to ask? It's nice to know that there are at least review sites that can assist me in my personal life. Similar to Here https://datingadvisor.ca/best-free-online-dating-sites-in-british-columbia-province/ I signed up for a senior dating site.

ghanshyam — November 3, 2021

Are you not getting a job and you are talking here in search of a job, so now you do not need to worry because now you can get a job at the press of a button,

Register now on IndisJob and get the job you want.

Jobs Related Blog

kadın spor ayakkabı — November 9, 2021

kadın spor ayakkabı

kadın topuklu ayakkabı — November 9, 2021

kadın topuklu ayakkabı

retro bowl — January 7, 2022

It is useful information, I have researched it and saved it, will be interested in the next sharing

Steven Johnson — January 20, 2022

Nice thread! Thanks!

John william — January 29, 2022

Technologistan is the popoular and most trustworthy resource for technology, telecom, business and auto news in Pakistan

samsung galaxy A32 price in pakistan

sunny hall — May 4, 2022

This is an excellent blog post. We found the documentation on your site to be quite helpful. The 2 games gartic phone and ovo game that I will introduce today are some of the hottest games today. Let's play and enjoy it

candy — July 1, 2022

You're giving away a fantastic resource, and you're doing so for free. I enjoy reading blogs that recognize the importance of providing high-quality resources for free mapquest driving directions.

Gure — August 23, 2022

But this lack of control made us feel and think about a lot of different things while we were recording. We found that making visuals was a good way to try to make sense of these data. We made visualizations of wavelengths to help us understand diary transcripts better. By putting them together, some of the "texture" of spoken words that is often lost during transcription is brought back (Smart 2009:296). This is from our new article in the journal Qualitative Research (Cottingham and Erickson Forthcoming). backrooms game

anibar.net — November 8, 2022

Your article was great and helpful

The sources from which you have collected information are very reliable and representative.

Thank you very much for this great content

Please also visit my site.

حمل بار به ایلام

حمل بار به سبزوار — November 13, 2022

I really like your content

And I enjoyed your website very much.

I hope you will always be successful

aloobar — November 13, 2022

I really like your content

And I enjoyed your website very much.

حمل بار به سبزوار

John Smith — November 30, 2022

I pretty much love everything about this–nice job!

towingkey

Thelaptops guide — May 31, 2023

Wow, this blog post completely blew my mind! The way you explained the concept was so clear and concise. I can't wait to share this with my friends and colleagues. Keep up the amazing work!"

Also visit this awesome blog - Legenda para foto sozinha

Click here — May 31, 2023

Great

Bimaspin — September 12, 2023

Bimaspin terkenal akan kemudahannya dalam mengakses situs dan kelancaran dalam bertransaksi.

leather motorcycle jacket brown — October 3, 2023

Buy now this jaceket

ساندویچ پانل — October 14, 2023

asia sandwich panel

درب سردخانه