Bemoaning how Halloween has turned into an opportunity/requirement for women and girls to dress sexy is nothing new. The trend isn’t just about Halloween, however, it reflects an everyday expectation for women. Women are expected to dress in ways that reveal their body and please a hypothetical male gaze daily. Men just aren’t.

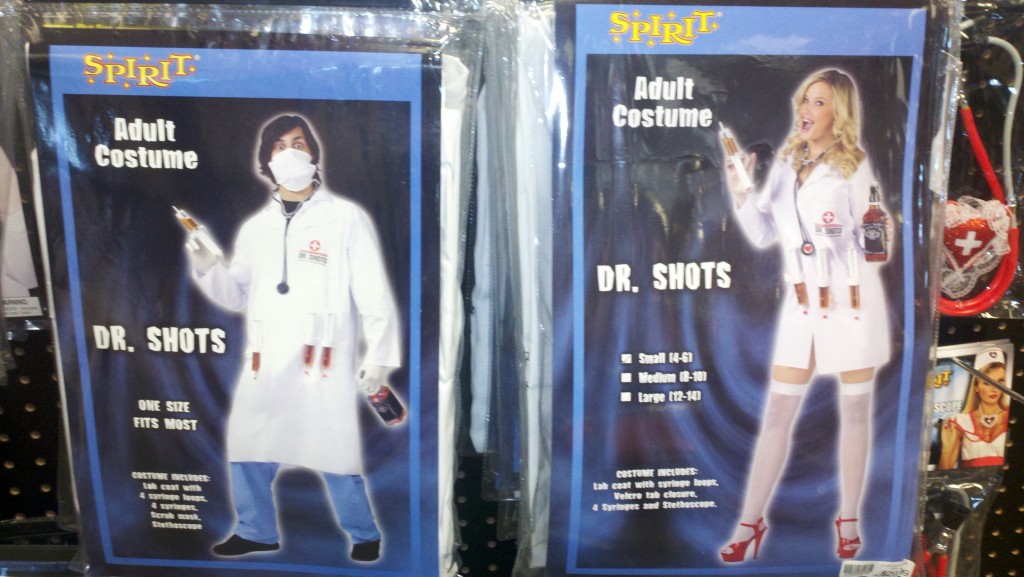

University of Akron sociology graduate student Will LeSuer took some great photographs illustrating the different expectations for men and women. The same idea for a costume is sexualized when it’s a woman in it and not-at-all sexualized when it’s a man. Notice, too, that the sizing is different. The costumes for women come in three sizes, while the men’s is usually just one size. This is because women are expected to wear clothes that reveal the shape of her body, so the exact size is more important.

You might have observed, also, that the costumes aren’t called “men’s” and “women’s.” They’re all just “adult.” So women could, if they wanted to, buy and wear the non-sexy version of the costume, and vice versa for men. And we might imagine a woman doing that. But would a guy do that? Probably only as a joke (unless they’re in a queer-safe space).

This pattern — women can dress like men, but men don’t dress like women — suggests that there is, in fact, something demeaning, ridiculous, or subordinating about presenting oneself to the male gaze. Most men feel stupid, gross, or vulnerable when they do it. This isn’t just about conformity to different gendered expectations. If it were just about difference women would feel equally weird dressing in men’s clothes. Instead, when women adopt masculine ways of dressing and moving, they often feel empowered.

So, when men do femininity they feel ridiculous and when women do masculinity they feel awesome. This is what gender inequality looks like.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.