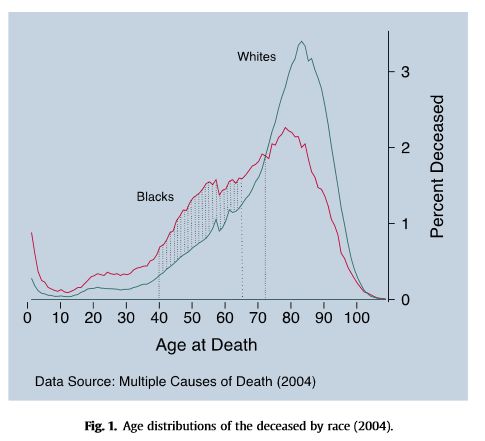

Black people in the U.S. vote overwhelmingly Democratic. They also have, compared to Whites, much higher rates of infant mortality and lower life expectancy. Since dead people have lower rates of voting, that higher mortality rate might affect who gets elected. What would happen if Blacks and Whites had equal rates of staying alive?

The above figure is from the recent paper, “Black lives matter: Differential mortality and the racial composition of the U.S. electorate, 1970-2004,” by Javier Rodriguez, Arline Geronimus, John Bound and Danny Dorling. A summary by Dean Robinson at the The Monkey Cage summarizes the key finding.

between 1970 and 2004, Democrats would have won seven Senate elections and 11 gubernatorial elections were it not for excess mortality among blacks.

At Scatterplot, Dan Hirschman and others have raised some questions about the assumptions in the model. But more important than the methodological difficulties are the political and moral implications of this finding. The Monkey Cage account puts it this way:

given the differences between blacks and whites in their political agendas and policy views, excess black death rates weaken overall support for policies — such as antipoverty programs, public education and job training — that affect the social status (and, therefore, health status) of blacks and many non-blacks, too.

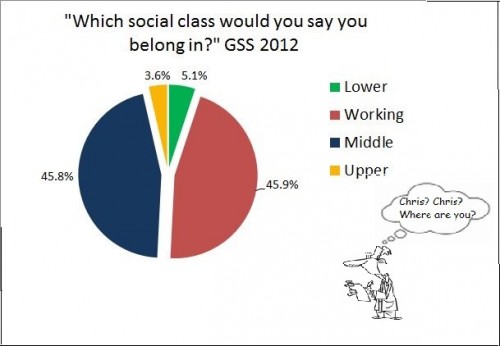

In other words, Black people being longer-lived and less poor would be antithetical to the policy preferences of Republicans. The unspoken suggestion is that Republicans know this and will oppose programs that increase Black health and decrease Black poverty in part for the same reasons that they have favored incarceration and permanent disenfranchisement of people convicted of felonies.

That’s a bit extreme. More stringent requirements for registration and felon disenfranchisement are, like the poll taxes of an earlier era, directly aimed at making it harder for poor and Black people to vote. But Republican opposition to policies that would increase the health and well-being of Black people is probably not motivated by a desire for high rates of Black mortality and thus fewer Black voters. After all, Republicans also generally oppose abortion. But, purely in electoral terms, reducing mortality, like reducing incarceration, would not be good for Republicans.

Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.