Usually, you want to match up with someone at about your level, or a little higher. The trouble is that many people overestimate their own level. Maybe that’s especially true of men.

One summer many years ago at the tennis courts, a guy I didn’t know came over and asked me if I’d like to play. I hadn’t arranged a game with anyone, but I didn’t want to wind up playing some patzer.

“Are you any good?” I asked. He paused.

“Well, I’m not Jimmy Connors,” he said (I told this was many years ago), “but neither are you.”

In chess and other games, serious players have ratings. Give a roomful of possible partners, they can sort through the ratings and find a match with someone at roughly the same level. It’s called assortative mating, though that term usually refers to the other kind of mating, not chess. It’s the basis of the conflict in this poignant scene from “Louie.”

Vanessa is not a ten, neither is Louie. According to principles of assortative mating, the tens will wind up with other tens, the nines with nines, and so on down the attractiveness scale. One problem in the “Louie” scene is that Louie seems to have an inflated view of his own attractiveness. He’s aiming higher than Vanessa. That’s typical. So is the importance that Louie, the man, places on physical attractiveness. This excerpt begins with Louie telling Vanessa that she’s a really beautiful . . . . He can’t bring himself to say “girl”; he’s probably going to say “person.” But he’s obviously not saying what he thinks.

Or as Dan Ariely and colleagues concluded from their study of HotOrNot members:

[Men] were significantly more influenced by the consensus physical attractiveness of their potential dates than females were. [Men also] were less affected by how attractive they themselves were . . . In making date choices, males are less influenced by their own rated attractiveness than females are.

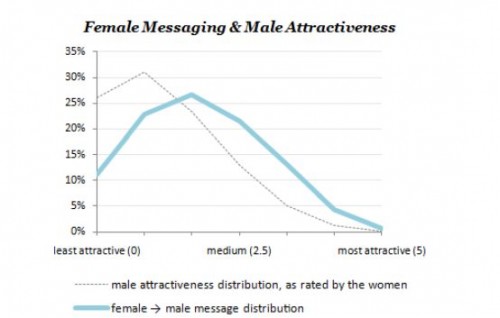

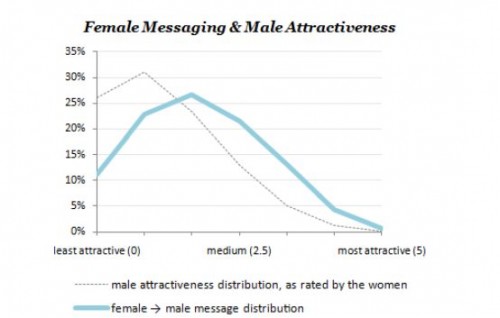

Another dating site, OK Cupid, found a similar pattern when they looked at data about who gets messages. They asked their customers to rate profile photos of the opposite sex on a scale of 0 to 5. They then tracked the number of messages for people at each level of attractiveness. The graph below shows what women thought and what they did – that is, how attractive they found men, and who they sent messages to.

Men who were rated 0 or 1 got fewer messages than their proportion in the population. That figures. But even men who were only moderately attractive got more than their share. Generally, the fewer men at a level of attractiveness, the fewer total messages women sent. The 4s, for example, constituted only 2% of the population, and they got only 4% of all the messages. The Vanessas on OK Cupid are not sending a lot of inquiries to guys who look like George Clooney.

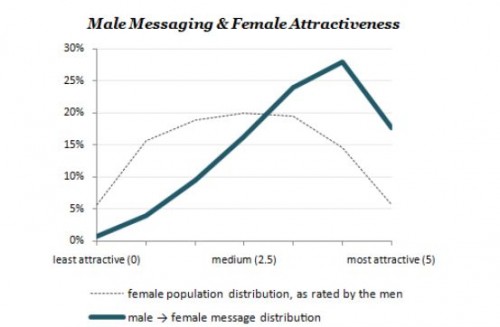

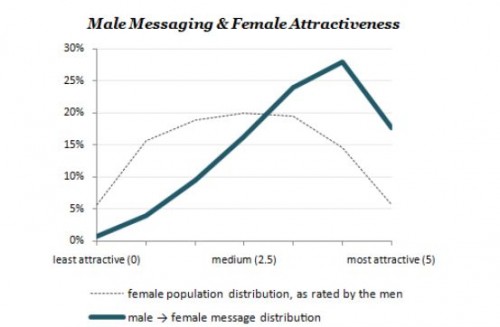

But look at the men.

Men are more generous in their estimates of beauty than are women. But they also ignore the Vanessas of the world (or at least the world of OK Cupid) and flock after the more attractive women. Only 15% of the women were rated as a 4, but they received about 26% of the messages. Women rated 5 received messages triple their proportion in the population.

What about those with so-so looks? Women rated as 2s received only about 10% of the messages sent by men. But men at that same level received 25% of the messages women sent. The women seem more realistic.

Vanessa too has no illusions about her own attractiveness. She refers to herself as “a fat girl,” and when Louie, trying to be kind, says, “You’re not fat,” she says: “You know what the meanest thing is you can say to a fat girl? [pause] ‘You’re not fat.’” But it’s only when she challenges Louie’s view of his own attractiveness that their relationship starts to change.

Y’know if you were standing over there looking at us, you know what you’d see?

What?

That we totally match. We’re actually a great couple together.

She doesn’t explain what she means by “totally match.” It could be their interests or ideas or personalities, but the imaginary stranger looking at them from over there couldn’t know about any of that. What that generalized other could see is that they are at roughly the same place on the assortative mating attractiveness scale.

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.