“Asshole is a wonderful word,” said Mike Pesca in his podcast, The Gist. His former colleagues at NPR had wanted to call someone an asshole, and even though it was for a podcast, not broadcast, and even though the person in question was a certified asshole, the NPR censor said no. Pesca disagreed.

Pesca is from Long Island and, except for his college years in Atlanta, he has spent most of his time in the Northeast. Had he hailed from Atlanta – or Denver or Houston or even San Francisco – “asshole” might not have sprung so readily to his mind as le mot juste, even to denote Donald Trump. The choice of swear words is regional.

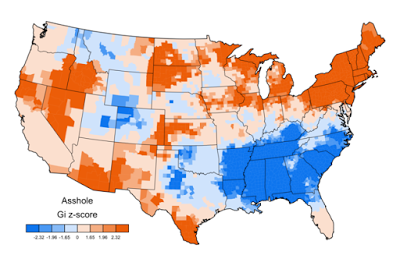

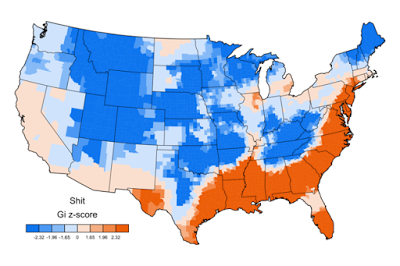

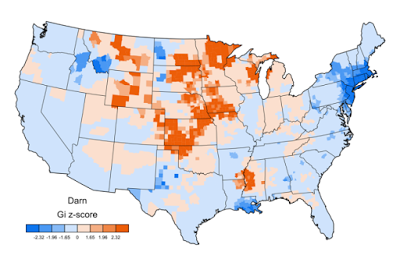

Linguist Jack Grieve has been analyzing tweets – billions of words – and recently he posted maps showing the relative popularity of different expletives. For example, every county in the Northeast tweets “asshole” at a rate at least two standard deviations above the national mean.

Less surprising are the maps of toned-down expletives. People in the heartland are just so gosh darned polite in their speech. When Donald Trump spoke at the Family Leadership Summit in Iowa, what got all the attention was his dissing of John McCain (“He’s not a war hero. … He is a war hero because he was captured. I like people who weren’t captured.”) But there was also this paragraph in the New York Times’s coverage:

Mr. Trump raised eyebrows with language rarely heard before an evangelical audience — saying “damn” and “hell” when discussing education and the economy.

“Well, I was turned off at the very start because I didn’t like his language,” Becky Kruse, of Lovilia, Iowa, said… Noting Mr. Trump’s comment about not seeking God’s forgiveness. “He sounds like he isn’t really a born-again Christian.”

Aside from the insight about Trump’s religious views, Ms. Kruse reflects the linguistic preferences of her region, where “damn” gets softened to “darn.”

Unfortunately, Grieves did not post a map for “heck.” (I remember when “damn” and “hell” were off limits on television, though a newspaper columnist, usually in the sports section, might dare to write something like “It was a helluva fight.”) You can find maps for all your favorite words at Grieve’s website, where you can also find out what words are trending (as we now say) on Twitter. (“Unbothered” is spreading from the South and “fuckboy” is rising). Other words are on the way down (untrending?). If you’re holding “YOLO” futures, sell them now before it’s too late.

Originally posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.