I would guess that most of us were unaware of the war on Christmas raging all around us until Bill O’Reilly started reporting from the front. He has since been joined by seasoned war reporters like Sarah Palin and Glenn Beck. I get the sense that they don’t really take themselves very seriously on this one – their war cries often sound like self-parody – and I guess that this attitude gives them license to say much that is silly and incorrect. Which they do.

I would guess that most of us were unaware of the war on Christmas raging all around us until Bill O’Reilly started reporting from the front. He has since been joined by seasoned war reporters like Sarah Palin and Glenn Beck. I get the sense that they don’t really take themselves very seriously on this one – their war cries often sound like self-parody – and I guess that this attitude gives them license to say much that is silly and incorrect. Which they do.

Still, these Christian warriors may be right about the general decline of Christian hegemony in American culture. What’s curious is how that historical trend seems out of sync with the historical trend in the war on Christmas. In fact, it looks like there was a similar war on Christmas 60-70 years ago, a war that went unnoticed.

O’Reilly’s war has two important battlegrounds – legal challenges to government-sponsored religious displays, and people saying “Happy Holidays” instead of “Merry Christmas.” He sets the start of the current war in the early years of this century. From Fox News Insider:

“Everything was swell up until about 10 years ago when creeping secularism and pressure from groups like the ACLU began attacking the Christmas holiday. They demanded the word Christmas be removed from advertising and public displays.”

Many people caved in to their demands, creating what O’Reilly has dubbed as the “Happy Holidays” syndrome.

If pushed, O’Reilly might trace the origins of the war back further than that – to the 1960s. That’s when the secularists and liberals started fighting their long war, at least according to the view from the right. It was in the 1960s that liberals started winning victories and when the world as we knew it started falling apart. In the decades before that, we took it for granted that America was a White Christian nation. We all pulled together in World War II without questioning that dominance. And our national religion continued to hold sway in the peaceful and prosperous 1950s. We even added “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance. And of course, we all celebrated Christmas and said, “Merry Christmas,” no questions asked.

But then came drugs, sex, rock ’n’ roll, protests against an American war, and “God is Dead” on the cover of Time. Worse yet, in 1963 the Supreme Court ruled that the establishment clause of the First Amendment meant that public schools (i.e., government-run schools) could not impose explicitly sectarian rituals on children. No Bible reading, no Christmas pageants.

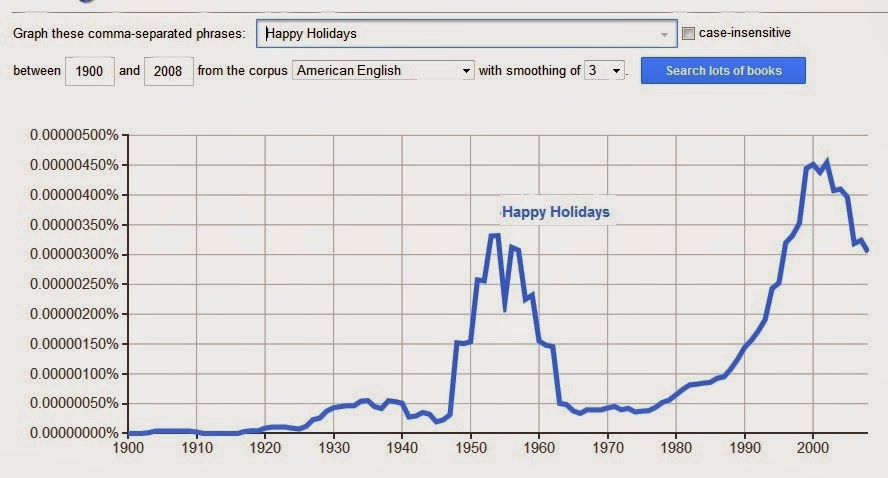

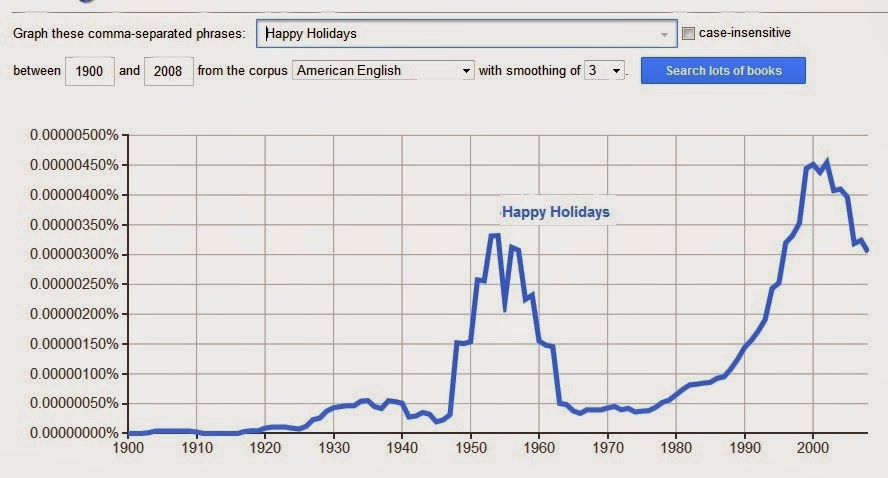

The trouble is that even if this history is accurate, it doesn’t have much to do with the War on Christmas, especially “the Happy Holidays syndrome.” I checked these two phrases at Google Ngrams – a corpus of eight million books.

The first big rise in “Happy Holidays” comes just after the end of World War II.

From about 1946 to 1954, it increases sixfold. It goes out of fashion as quickly as it came in, and even in the supposedly secular 1960s, it rarely turned up (at least in the books scanned by Google). The next rise does not begin until the late 1970s, continues through the Reagan and Clinton years.

But just when O’Reilly says the War started, “Happy Holidays” starts to decline.

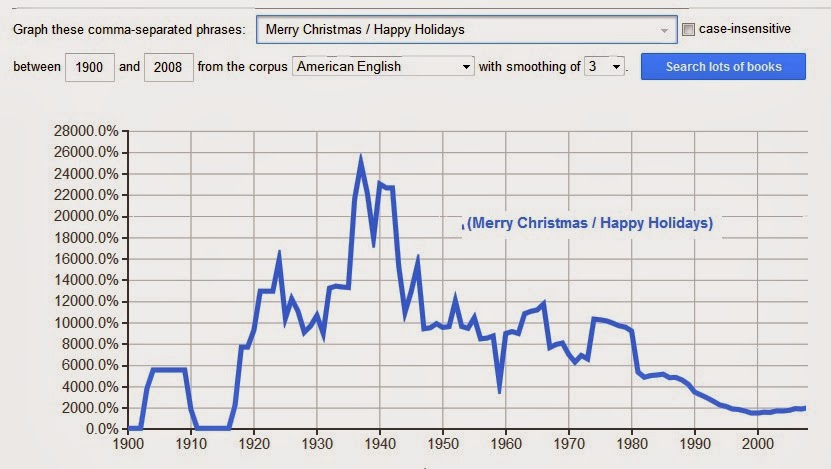

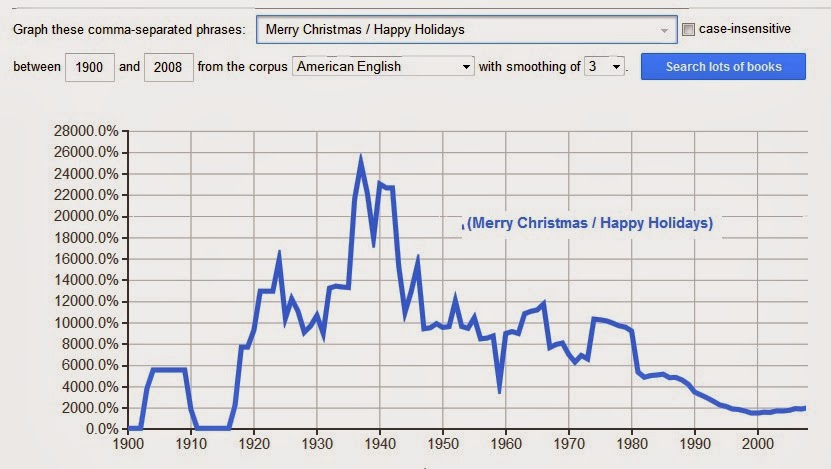

And what about “Merry Christmas”? According to the War reporters, the new secularism of the last ten years has been driving it underground. But Ngrams tells a different story.

If there was a time when “Happy Holidays” was replacing “Merry Christmas,” it was in the Greatest Generation era of the 1940s. Since the late 1970s, when “Happy Holidays” was rising, so was “Merry Christmas.” Apparently, there was just a lot more seasonal spirit to go around.

Perhaps the best way to see the relative presence of the two phrases is to look at the ratio of “Merry Christmas” to “Happy Holidays.”

In 1937, there were 260 of the religious greeting for every one of the secular. In the 1940s the ratio plummeted; by the late 1950s it had fallen to about 40 to one. In the Sixties, “Merry Christmas” makes a slight comeback, then declines again.

By the turn of the century, the forces of “Merry Christmas” are ahead by a ratio of “only” about 18 to one. Since then – i.e., during the period O’Reilly identifies as war time – the ratio has increased slightly in favor of “Merry Christmas.”

O’Reilly may be right that at least in public greetings – by store clerks, by public officials, and by television networks (even O’Reilly’s Fox) – the secular “Happy Holidays” is displacing the sectarian “Merry Christmas.” But that still doesn’t explain a similar shift over a half-century ago, another war on Christmas that nobody seemed to notice.

Cross-posted at Montclair SocioBlog.

Jay Livingston is the chair of the Sociology Department at Montclair State University. You can follow him at Montclair SocioBlog or on Twitter.