Earlier this year, Cambodia marked the 40th anniversary of the collapse of the Khmer Rouge and the end of the genocide that left an estimated 1.5 to 2 million people dead and countless Cambodians displaced. It made sense then for the largest academic group dedicated to the study of genocide, the International Association of Genocide Scholars (IAGS), to host its biannual conference in Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh, this past July. The conference would provide an opportunity for the country to demonstrate its resiliency and give attendees (myself included) a chance to see the lingering effects of mass violence in a place where its impacts are still clearly visible and permeate nearly every aspect of society.

Everybody has a family narrative or childhood story to tell. Elizabeth Warren’s is about her Native American ancestor; my mother’s about her German Jewish neighbor. And while Elizabeth Warren’s ancestor remains elusive, my mother’s neighbor and what I heard about him growing up has become more concrete over the years. It literally became concrete when in 2005 a Stolperstein (stumbling stone) bearing his name was installed in front of the house he had owned before he was deported and murdered in Theresienstadt.

Here is the story my mother told me. It was in late 1941 when she noted that Sally Cohen, an older gentleman and respected citizen (so she thought) had to wait in the corner of the neighborhood bakery store until everybody else was served. She also noted that he was now wearing a monstrous star-shaped yellow badge that said, “Jude.” My mother was 11 at the time and to this day hasn’t forgotten the sad and embarrassed look on Herr Cohen’s face. When she asked the adults why Herr Cohen was treated that way, she was told not to worry and that all of this was mandated by a new law.

The following offers a recap, an update and another perspective to the Waldsee issue previously discussed in this blog 3/25/3019 by George Dalbo under the title “More than a name…

Thomas Schmidinger teaches at the University of Vienna in

He is an expert on Syria, Iraq, and Iran and the author of a number of books on migration, cultural integration, and the Middle East, several of which have been translated by U.S. publishers.

Dr. Schmidinger was invited by multiple U.S. Universities, institutions, and bookstores to give a series of lectures this September on his newest book, The Battle for the Mountain of the Kurds: Self-Determination and Ethnic Cleansing in the Afrin

When Dr. Schmidinger arrived at the boarding area on

Kathryn Agnes Huether was born and raised in rural Montana. As the daughter of a music teacher and a school superintendent, music and education were always at the center of her life. At the age of 4, Kathryn’s mother, Renée, introduced the violin into her life, driving 100 miles one way for a half-hour violin lesson. Renée’s dedication to her daughter’s musical training dynamically shaped Kathryn’s worldview and studies, as did David, her father, who exemplified hard work and kindness. Kathryn graduated with a double BA in Violin Performance and Religious Studies from Montana State University in 2013. Following undergrad, Kathryn went on to attend the University of Colorado-Boulder, where she received a Master’s in Religious Studies, with an endorsement in Jewish Studies. Her first Master’s thesis was the catalyst for her PhD research, as she examined the soundtracks of two Holocaust film documentaries, Night and Fog (1956) and Auschwitz Death Camp: Oprah, Elie Wiesel (2006), arguing that the accompanying soundtracks subjectively influenced a viewer’s reception and understanding of the documentary material presented.

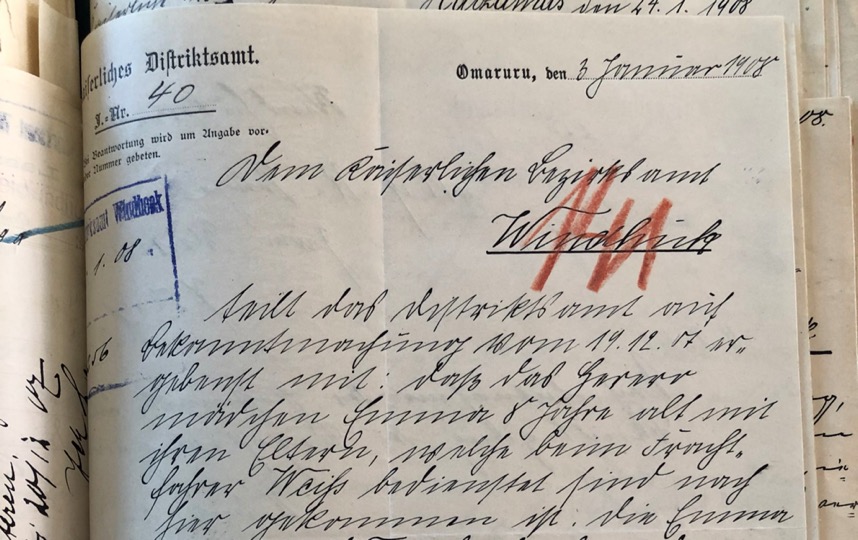

Germans also separated children from their parents. In a previously unknown collection at the National Archives of Namibia in Windhoek, I recently discovered documents that confirm colonial authorities used family separation as a means of domination in German Southwest Africa (present-day Namibia), Germany’s first and only settlement colony.

A dispatch to the Omaruru District Commander, for instance, details the separation of Emma, an 8-year-old Herero girl, from her parents as they departed from the capital city of Windhoek. It concludes that “she ran after her parents since she belongs with her Omaruru family.” Emma’s fate remains a mystery to the present day.

Genocide studies

To interpret images of genocide consequently involves a double competence, which puts genocide specialists (historians, anthropologists, sociologists, psychologists, among others) and image analysts (semiologists, film or photography historians, new media specialists) in a separately delicate situation. The task demands the command of theory and methods within multiple scholarly fields, including specific instruments for the analysis of visual texts. The question continues to be: what can the image contribute –as iconography and as a visual narrative– to the comprehension of genocide and mass violence that could not be gained from other available documents which were traditionally studied by the discipline of history. This is a

This past June, the Memory Studies Association held its Third Annual Memory Studies Conference at the historic Complutense University Madrid. Hundreds of memory scholars from all over the world flocked to the city for the four-day conference, which was co-sponsored by the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies. The conference primarily took place at the Faculty of Philology buildings, which was a fitting location (considering its central role during the Spanish Civil War) to contemplate and reflect on the role of memory in our world today.

In this interview with Yagmur Karakaya, Prof. Olick demystifies processes involved in collective memory, discusses the role of emotions and nostalgia in remembrance, and introduces the notion of regional constellations of memory. Olick also untangles the fruitful concept of “legitimation profiles”, which he applies in his latest book to the ways Germany confronts the specters of its Nazi past.

Jeffrey Olick is a professor of sociology and history and chair of the sociology department at the University of Virginia. He is a cultural and historical sociologist whose work has focused on collective memory and commemoration, critical theory, transitional justice, postwar Germany, and sociological theory more generally. His books include “The Politics of Regret: On Collective Memory and Historical Responsibility,” and “The Sins of Fathers: Germany, Memory, Method”.

(Editor’s note: This is a condensed version of our interview with Dr. Olick. Follow the link at the end to read the interview in its entirety.)

The roots of today’s racial and religious structures can be found in late medieval Spain and its colonies. It was in the Iberian Peninsula, during the fifteenth century, that terms like