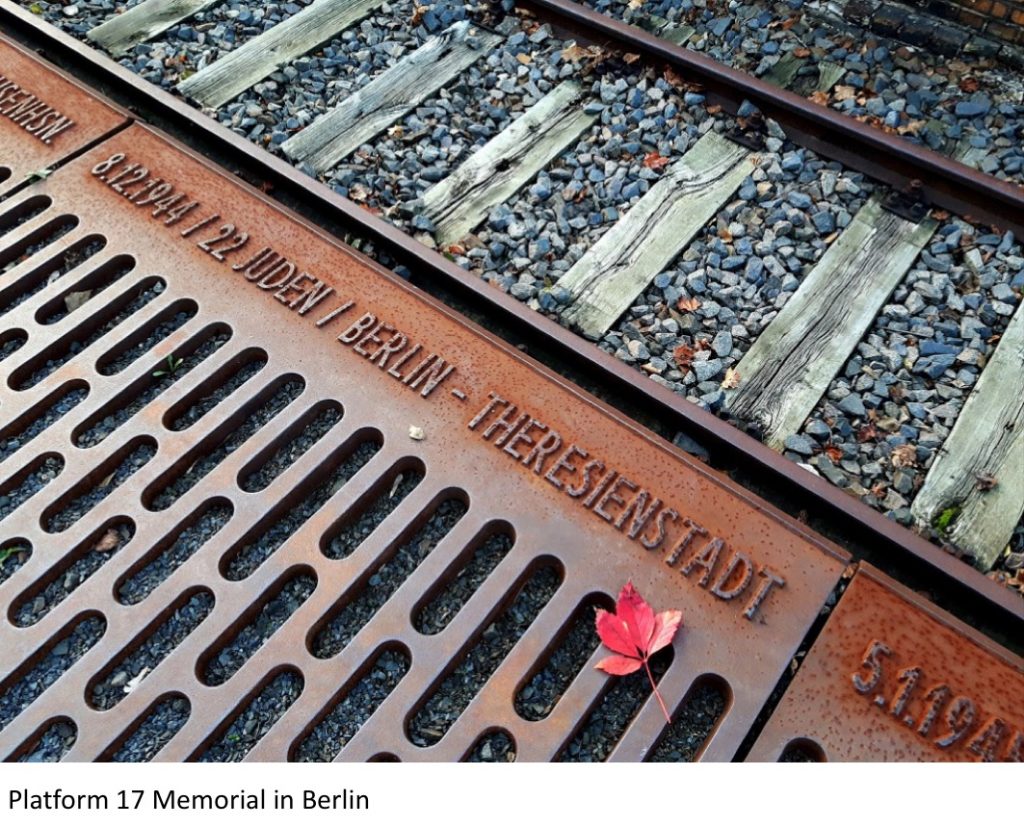

“Ever since the Holocaust, in which six million European Jews – among other victims – were deliberately targeted and destroyed, a moral hierarchy of suffering has seized the humanitarian imagination, one in which stories of victimhood are ranked based on the scale of human destruction. Genocide has become a numbers game. In this spectacle of suffering, the bodies of victims literally count” (Meierhenrich 2020, 4).

The figure of 800,000 Rwandan deaths has long been associated with the Rwandan genocide. It has been widely cited in scholarly works, documentaries, museums, and memorials. This casualty figure, while widely cited, is also highly contested. In the most recent edition of the Journal of Genocide Research (2020), this figure is methodologically deconstructed and debated. While the figures modeled in the journal are also contested by scholars, the debates surrounding the politics of numbers raise important questions and concerns about how victimhood is constructed in the wake of genocide and mass atrocity.