No, I am not talking about the Vatican or the next Coen Brothers movie. I am talking about old men saving countries.

The man that comes to my mind can be described as follows: practicing Catholic with a pragmatic mindset that enables him to reach across the aisle; lawyer by training and politician by vocation who experiences personal tragedy — the loss of his wife — early in his career. That would be Konrad Adenauer, West Germany’s first chancellor after WWII, and those are not the only attributes he shares with Joe Biden.

-

Konrad Adenauer -

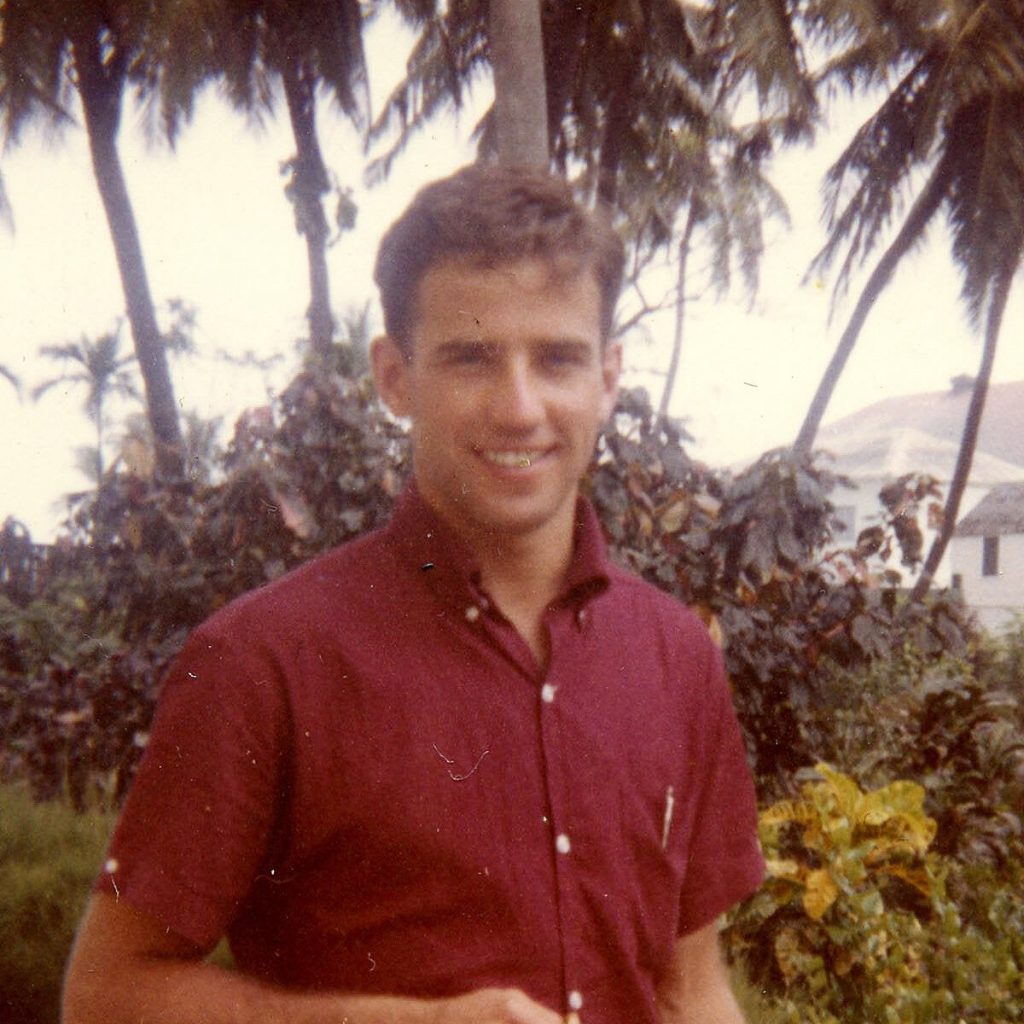

Joe Biden