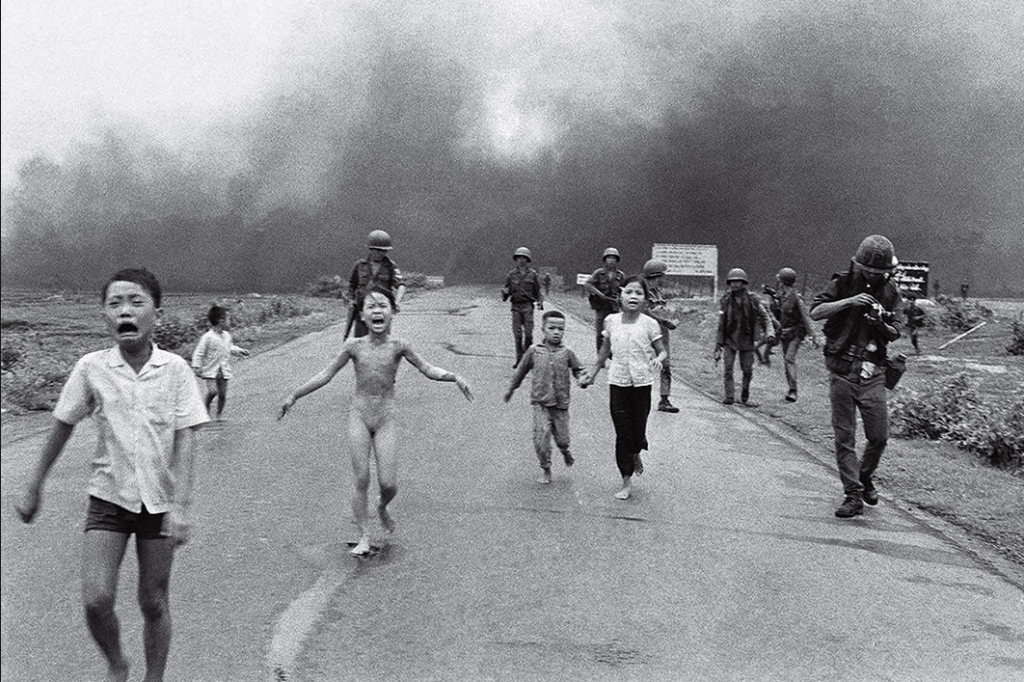

In 2015 I travelled to Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. As a U.S. citizen, I worried about how I would be received. Born in 1968, I grew up hearing Walter Cronkite’s nightly reports of American casualties during what U.S. media accounts commonly called the Vietnam War (1955-1975). I remember the famous 1972 picture of a Vietnamese girl running naked from a bombing campaign using napalm, a slick, sticky petroleum. Napalm had seared the girl’s skin. Her agonized distress while running on a road with other screaming Vietnamese children, followed by armed and seemingly nonchalant soldiers, confused and sickened me. The black and white, Pulitzer-prize winning picture stood in contrast to full-color film clips I also remember of the war, clips shot from U.S. bombers whose payloads created massive, spectacular orange fireballs against the lush green jungle.

My interest in genocide studies surely grew from my childhood exposure to such images. In On Photography, Susan Sontag (2001) said she was forever changed from seeing a picture from the Holocaust as a youth, a photograph that she said divided her life in half, from innocence to a new vision of vomitus human cruelty. Now traveling as an adult in Ho Chi Minh City, I felt unease and shame. I knew of the atrocities perpetrated by U.S. soldiers on unarmed women and children. I had become aware of the massive and indiscriminate U.S. bombing campaigns against Vietnamese and other Southeast Asian citizens. I had learned of the ongoing effects of the U.S. use of chemical weapons like napalm and Agent Orange. Despite being a child during the war, as a now-adult citizen of the aggressor nation I felt complicit—that in my brazen appearance on Vietnamese soil, I could not escape judgment for my country’s policy decisions and atrocities.

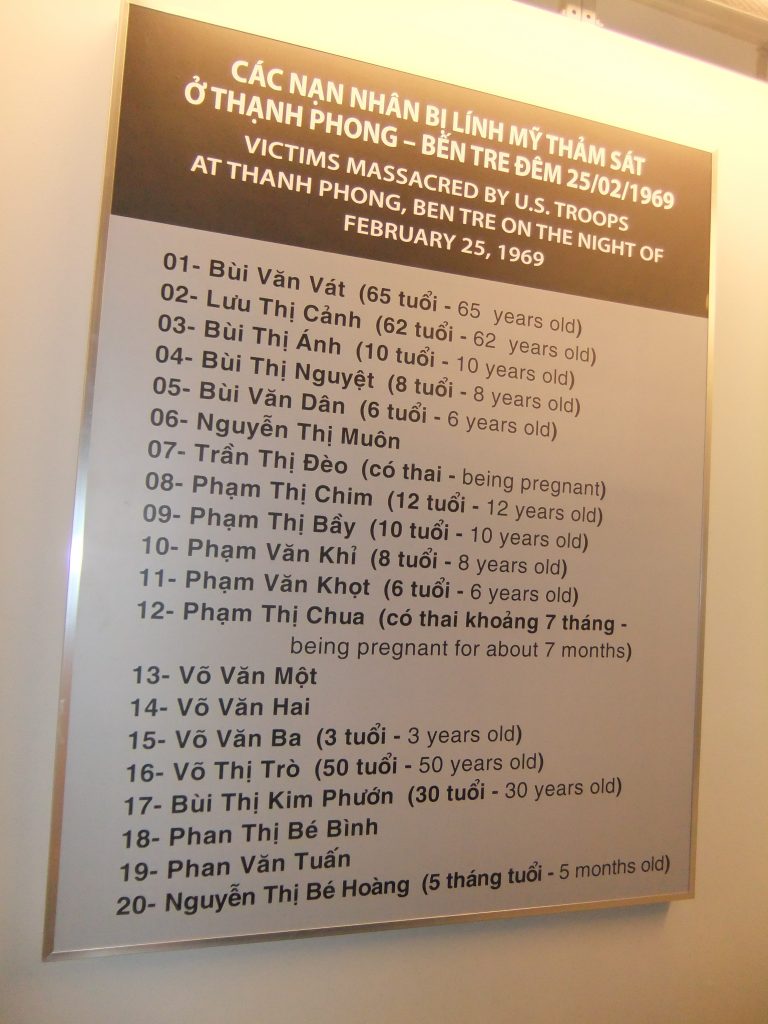

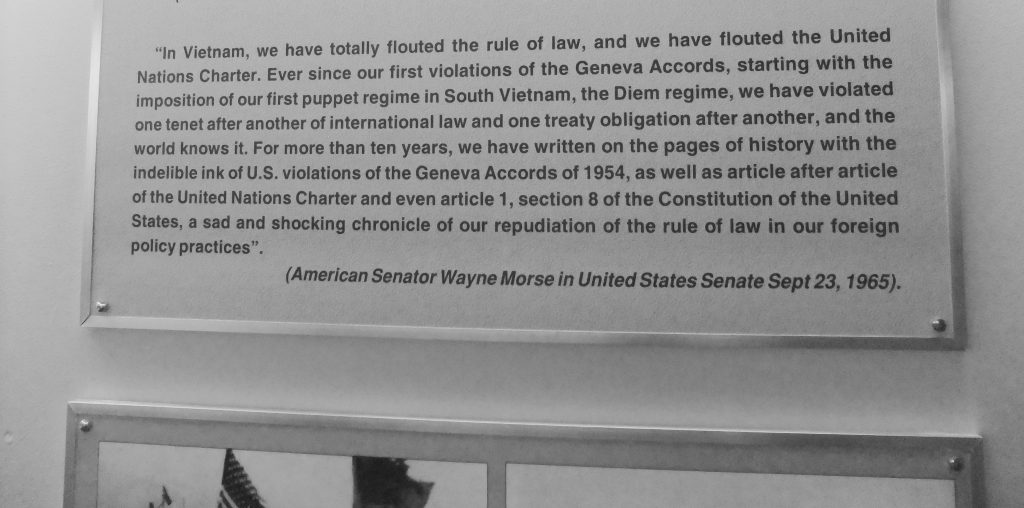

Still, I found it unsettling to visit Ho Chi Minh City’s War Remnants Museum. Once named the Exhibition House for Crimes of War and Aggression, its name was changed following the normalization of Vietnamese and U.S. relations in 1995. The museum, though, uses the phrase “the American War” throughout, as opposed to what U.S. citizens call “the Vietnam War.” The museum’s exhibition of the material was frank and persuasive, without much commentary. I found a statement from U.S. Senator Wayne Morse that the U.S. had flouted the rule of law during the war. Quotes in the museum from the Geneva Convention can be contrasted against photographic evidence of the My Lai massacre, the shells of massive bombs, and charts outlining the tonnage of U.S. bombs dropped on Vietnam (tonnage estimated as perhaps double what was used in all of World War II). Here was undisputed material. Americans had fought the war in Vietnam. Vietnam never attacked U.S. soil. It was a war of aggression carrying the hallmarks of genocide (Lemkin 1944). In the American War, unarmed U.S. women and children did not suffer and die. U.S. villages were not razed. Chemical weapons were not deployed on American soil.

Perhaps the images and other material in the museum were especially upsetting for me as I was now surrounded by Vietnamese people and international visitors. We viewed the images together. A specific area of the museum devoted entirely to images of deformed fetuses and children, victims of Agent Orange, also left no doubt that Vietnamese people would long suffer the effects of this war. A war resulting in genetic mutations arguably never ends.

I wish more Americans could see the War Remnants Museum. While it can be perceived as promoting a form of Communist Party nationalism (Giller 2014), it might also give Americans pause to consider both America’s immense power on the world stage and the results of war. The War Museum can be seen as propagandistic and one-sided, but perhaps American visitors could simply see that war is understood in many ways (Schwenkel 2009). Gently phrased, the world outside of the U.S. at times views its actions unfavorably. Shame is a powerful emotion and is perhaps the first step toward reconciliation—if shame is expressed by the citizens of the once-invading country, the victims and other observers can see that the event horrifies some citizens from the responsible country. Carefully walking through such a museum can also disabuse visitors of simple ideas that history is a collection of events neutrally observed and recorded. Public displays of war atrocities, seen by U.S. citizens, might promote U.S. accountability for and acknowledgment of U.S. war crimes. Such public displays, upsetting as they are, might further reduce future support for wars that feature indiscriminate killing.

Later that same trip, I wait in a line several blocks long to see the Ho Chi Minh Mausoleum in Hanoi. A little girl standing nearby with her classmates, in her school uniform, says hello to me in English. She asks where I am from. When I say the United States, she replies “welcome to Vietnam.” I was humbled. The girl was kind and magnanimous, like all the Vietnamese people I met that trip. This child-welcoming me would know the prolonged effects of the American War. She will learn about the history of her country. She seemed younger than nine years old, the age of the girl in the photograph I cannot forget, the girl whose skin was burning. She will see that picture. U.S. citizens should also see it, particularly through Vietnamese eyes.

Kurt Borchard is Professor of Sociology at the University of Nebraska Kearney. He was a participant in the 2019 CHGS summer workshop for teachers. He teaches an undergraduate course on the Holocaust and has written extensively on cultural studies and homelessness.

References:

Gillen, Jaime. 2014. Tourism and Nation Building at the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. DOI:10.1080/00045608.2014.944459.

Lemkin, Raphael. 1944. Axis Rule in Occupied Europe. Washington D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Schwenkel, Christina. 2009. The American War in Contemporary Vietnam: Transnational Remembrance and Representation. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Sontag, Susan. 2001. On Photography. New York: Picador.

Comments 1

JOhnni Lewis — June 19, 2020

“Communist party nationalism,” just what is that? The Communist Party of Vietnam led the fight of the people of Vietnam in the American War on their country. Communist Party members fought and died by the hundreds of thousands in this war. The war was about self-determination of nation oppressed by imperialism.

Why must you allow the communist red-herring always be thrown in the mix? It is not the business of any American To question the methods by which an oppressed nation wins its liberty.

During the American War on Vietnam, I was a solider in the US Army. I refused orders to go Fight this war and ended up in military prison. I KNEW what that war was about even though i was only 23. I KNEW innocent people were being killed. I KNEW I wanted no part of it—and so did hundreds of thousands of other soldiers.

You never hear much from us, or about us, but in 1969 when I was in the Fort Dix Army Stockade awaiting courts martial for refusing to go to the American War in Vietnam, there were hundreds of others there with me. Overwhelmingly, those soldiers were black, Latino, and other of color and working class soldiers.

And, overwhelmingly there were given bad discharges, and today for their entire lives they did not and have received any benefits from the Veterans Administration due to these discharges. For this refusal to fight in the genocidal American War on Vietnam, they have suffered their entire adult lives as outcasts.

While at the same time, millions said YES to the war and became killers or complicit-killers and get all manner of benefits. They are treated with respect, and why is that?

You must rankle at my audacity to call into question respect of veterans who fought in wars of conquest and oppression. But the legacy they share is the murder and carnage they wreaked not only on the countries of Vietnam and Korea—yes, there was an American War on Korea, too—but also Laos and Cambodia, and before that Indonesia, and the Philippines, and Cuba, and Iraq, and Afghanistan, and on and on ... And presently there are US troops on 800 military bases and ships around the world.

Yes, lamenting what the United States of America did to The people and the land Vietnam is right and proper, but this war continues on at a never stop pace against other peoples, other lands ...