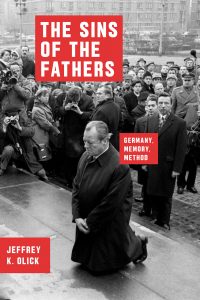

There is no state that has been and continues to be as haunted by the specters of a criminal past as is Germany. What happens when State leaders cannot tell a positive story about the nation’s past? A damaged national identity is, of course, not unique to Germany. For German leaders, however, the task at hand was, and continues to be, the mastering of a past that has become the symbol of ultimate evil. Jeffrey Olick’s The sins of the fathers: Germany, memory, method examines, with an impressive wealth of documentation and meticulous attention to detail, the process by which the Federal Republic of Germany (1949–1990) confronted the burden of the Nazi crimes and dealt with its political costs.

There is no state that has been and continues to be as haunted by the specters of a criminal past as is Germany. What happens when State leaders cannot tell a positive story about the nation’s past? A damaged national identity is, of course, not unique to Germany. For German leaders, however, the task at hand was, and continues to be, the mastering of a past that has become the symbol of ultimate evil. Jeffrey Olick’s The sins of the fathers: Germany, memory, method examines, with an impressive wealth of documentation and meticulous attention to detail, the process by which the Federal Republic of Germany (1949–1990) confronted the burden of the Nazi crimes and dealt with its political costs.

Germany’s ‘legitimation profiles’

Jeffrey Olick argues that ‘much of the state-sponsored memory in the Federal Republic of Germany has been organized as an effort to deny collective guilt’ (p. 29). The book is structured around the presentation of three succeeding ‘legitimation profiles’ – each confronting the problem of collective guilt in singular ways.

The first one, the ‘reliable nation’, which was centered on institutional reform, rather than symbolic gesture, aimed to prove that the newfound German state was a trustworthy and responsible member of the international community. During this time, the country’ s leaders draw a clear line separating the criminal Nazi leadership from the general German population. The Nazis had committed crimes ‘in the name of the German people’, as chancellor Adenauer put it in the1950s.

In March 2006, performance artist Santiago Serra constructed a homemade gas chamber inside a former synagogue in the Cologne area and invited Germans to be symbolically gassed. Exhaust pipes from six cars were hooked to the building, which was then filled with deadly carbon monoxide and visitors entered the space wearing protective masks. What was the artist’s intention? Serra said his aim was to give people a sense of the Holocaust. The Jewish community was furious. It was considered a provocation at the expense of Holocaust victims, an insult to survivors and the whole community. “What’s artistic about attaching poisonous car exhaust into a former synagogue?” said writer and Holocaust survivor Ralph Giordano (1923-2014), “and who gave permission for this?”

In March 2006, performance artist Santiago Serra constructed a homemade gas chamber inside a former synagogue in the Cologne area and invited Germans to be symbolically gassed. Exhaust pipes from six cars were hooked to the building, which was then filled with deadly carbon monoxide and visitors entered the space wearing protective masks. What was the artist’s intention? Serra said his aim was to give people a sense of the Holocaust. The Jewish community was furious. It was considered a provocation at the expense of Holocaust victims, an insult to survivors and the whole community. “What’s artistic about attaching poisonous car exhaust into a former synagogue?” said writer and Holocaust survivor Ralph Giordano (1923-2014), “and who gave permission for this?”

The semester is about to start and I find myself touching up syllabi and putting some order in my course material. While reviewing files, I came across a very helpful handout from a

The semester is about to start and I find myself touching up syllabi and putting some order in my course material. While reviewing files, I came across a very helpful handout from a  There are many that contend today that the Holocaust’s global presence and iconic status obscures other forms of mass violence, and even the acknowledgment of other genocides. Elie Wiesel’s seminal role in Holocaust memorialization worldwide demonstrates exactly the opposite. The proliferation of Holocaust remembrance, education and research efforts has been extraordinarily influential in the moral and political debates about atrocities, and in raising the level of attention to past violence and responsiveness to present genocide and other forms of gross human rights violations.

There are many that contend today that the Holocaust’s global presence and iconic status obscures other forms of mass violence, and even the acknowledgment of other genocides. Elie Wiesel’s seminal role in Holocaust memorialization worldwide demonstrates exactly the opposite. The proliferation of Holocaust remembrance, education and research efforts has been extraordinarily influential in the moral and political debates about atrocities, and in raising the level of attention to past violence and responsiveness to present genocide and other forms of gross human rights violations. In 1999 Joschka Fischer, Germany’s Foreign Minister and a member of the Green Party with strong pacifist roots, used the phrase “Never Again Auschwitz” to support German military intervention during the Kosovo crisis. In 2005, at the main ceremony to mark the 60th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz camp, Russian President Vladimir Putin praised the Red Army for “liberating Europe” (an assertion that obviously did not resonate positively among Poles). In the summer of 2014 Turkish President Recep Erdoğan slammed Israel for betraying the memory of the Holocaust by “acting like Nazis” during the operation against Hamas in Gaza. At the same time Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu invoked the Holocaust to warn the world of a nuclear Iran.

In 1999 Joschka Fischer, Germany’s Foreign Minister and a member of the Green Party with strong pacifist roots, used the phrase “Never Again Auschwitz” to support German military intervention during the Kosovo crisis. In 2005, at the main ceremony to mark the 60th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz camp, Russian President Vladimir Putin praised the Red Army for “liberating Europe” (an assertion that obviously did not resonate positively among Poles). In the summer of 2014 Turkish President Recep Erdoğan slammed Israel for betraying the memory of the Holocaust by “acting like Nazis” during the operation against Hamas in Gaza. At the same time Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu invoked the Holocaust to warn the world of a nuclear Iran.