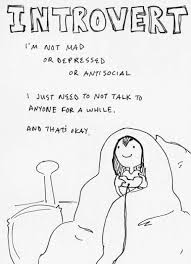

![I LOVE this. [Image credit: Schroeder Jones]](https://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/files/2013/08/introverts.jpg)

We were three awkward, shy, 13-year-old girls; we were not, by any stretch of the imagination, “popular.” Surreptitiously read women’s magazines had taught us to seek self-knowledge through multiple-choice questions, while standardized tests had trained us to endure answering many multiple-choice questions in a row. The book’s subject matter promised to help us sort out everything that had perplexed us about interacting with others, and the title alone resonated with particular force. We worked diligently and with enthusiasm, and perhaps unsurprisingly (given the way our culture socializes girls), all three of us tested identically: At the time, we all came out INFP.

And we rejoiced. Suddenly, we had answers. We weren’t outcasts or “nerds” or any of the other names that I, in particular, got called that year, oh no: we were a rare personality type, one that the book said makes up only one percent of the entire human population. We were special—and now that we had a name, we were proud. We set about planning The First (and only) Annual INFP Fest, a sleepover event for which we made fliers even though we had no intention of inviting anyone other than ourselves. We got dressed up and got dropped off at the Hard Rock Cafe downtown; I even got a fresh (also, my last ever) permanent wave for the occasion. We had an identity to celebrate, and so could take ourselves seriously now. It was a very big deal.

This was my first experience with Introvert Pride.

My personality has since wandered in and out of a couple different Myers-Briggsville neighborhoods, but to this day I test “introvert” on any test form that has more questions about how the test taker experiences social interaction rather than how the test taker acts in social situations (which makes perfect sense, if you ask me). The tests might even be right: If there’s one pair of things that drives some people close to me insane, it’s that I’m PITA-level precise with my language and often go “straight to the big issues,” which apparently makes me a card-carrier as far as researchers are concerned. I still remember when someone forwarded me Jonathan Rauch’s essay, “Caring for Your Introvert” in 2003, as well as the simultaneous thrill of recognition and relief that hit me as I read it (and then re-forwarded it further). I still love Schroeder Jones’s 2012 comic “Guide to Understanding The Introverted” and, until I thought too sociologically about it, I was even enjoying introversion’s appearance as a meme. (Here is a whole bunch of stuff, all of it just from August 2013, that is about introversion or introversion versus extroversion.) Granted, the Introversion Meme may not be what you’d call “true to the concept,” especially when it comes to differentiating[ii] between “introversion” and “shyness,” but overall, I was thinking the meme-ification of introversion was a net positive (no pun intended).

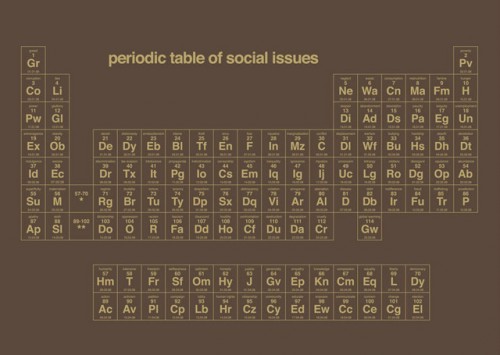

Here’s why I was into it: Present-day expectations for normative social behavior map much more closely onto extravert preferences than they do onto introvert preferences (at least in the U.S.), but the burdens of these expectations are not equally distributed. If a man of sufficient privilege is reserved, serious, does not engage in small talk, and does not mingle readily with others at parties, he stands a good chance of being read as very important, very interesting, or very smart. A man with less privilege who doesn’t smile and engage in pleasantries, however, runs the risk of being read as menacing, hostile, or aggressive (especially if he isn’t white). Similarly, a woman who is more reserved will likely be read as cold, uptight, haughty, standoffish, self-important, or—my favorite—“bitchy,” and women in particular are expected put others at ease by filling would-be silences with small talk (because while silence is considered awkward, ‘big talk’ from a woman would be threatening). In short, the interactional styles and behaviors captured by the pop definition of “introversion” have generally been more acceptable for privileged men than for Others. By repackaging these non-normative styles and behaviors in a concept that is at least purportedly gender-, race-, and class-neutral, it seemed to me that the Introversion Meme just might put a dent in making it more acceptable for Others to forgo the social- and emotional labor of performing friendly deference in order to make members of dominant groups feel more comfortable.

And yet, on closer examination, there are critical issues with the Introversion Meme as a tool for activism and social justice. Extending the range of what’s considered “normal” is still normative, and using the Introversion Meme to say, “This is why I am like this,” still casts introverted preferences as things that need to be justified or accounted for. For example: It turns out that I’m not terrible at talking to strangers, but I loathe small talk. I’m not good at it; it stresses me out when other people do it at me; I find companionate silence and conversations of substance to be far more comfortable and pleasurable. Yet I’m also aware that, as a woman (and a younger one at that), I am especially expected to be “pleasant” and talkative, to do the “nurturing” work in social interactions, and to shape my behavior around others’ needs and pleasures. My personal preferences and inclinations are therefore in conflict with social norms for people of my demographic—but how to address that fact? On the one hand, I can insist upon “being myself” as a political act Because Screw Normative Expectations, but that strategy is going to cost me social capital (and probably won’t make me a whole lot of friends). Alternatively, I can pull out the Introversion Meme to explain myself, but to do so is to shift the conversation from gender and power to why I, personally, am “like that.” While invoking “introversion” might be less of a hassle, I’m not certain that doing so is worth the ideological and political price.

The other thing about the Introversion Meme is that—and this might not make sense at first, so bear with me—beneath its dork-positive surface, the Introversion Meme has roots in digital dualism. Wait, what? Introverts tend to like the Internet, and tend to be comfortable with technologically mediated interaction, so you’d think introverts (of all people!) would be less likely to denigrate or discount digital interaction. Yet the rise of the Introversion Meme isn’t actually about introversion or introverts; it’s about turning away from what is meaningless and shallow, and toward what is ‘deep, meaningful, and true.’ Sound familiar?

Introversion is the new “disconnection,” and the Introvert fetish is the new IRL fetish.

Recall the relationship between digital dualism and the IRL Fetish (both concepts Nathan Jurgenson’s handiwork): digital dualism marks a conceptual division between “online” and “offline” that falsely construes digitally mediated experiences as somehow separate from other experiences, and that often leads us to denigrate or dismiss digitally mediated experiences as less real or less important than other experiences. The IRL Fetish, in turn, is when we elevate things we think of as “offline” to hold them up as aesthetically, qualitatively, and morally superior to things we think of as “online.” This comparatively recent (over)valuing of “offline” objects and experiences doesn’t stem from some change in their intrinsic properties, however. Rather, we ascribe more value to certain “offline” objects and experiences—which we misleadingly label “real,” as if online objects and experiences were not equally real—because they now serve as symbols (fetishes) that represent both the superiority of the precious, authentic “offline” and the inferiority of the hollow, ubiquitous, ever-encroaching “online.” Accordingly, the Disconnection Meme—in which “disconnecting,” “unplugging,” “logging off,” taking a “screen vacation” or “digital detox” (etc.), is framed as a way to retrieve, revive, or rediscover the real, meaningful, pleasurable, authentic, significant, or important things in life—is IRL fetishism par excellence.

Just as the Introversion Meme’s “introversion” isn’t exactly what psychologists have in mind when they use the word, neither is the Introversion Meme’s “extroversion” what psychologists mean when they say “extraversion.” In meme caricature, “extroversion” is marked by superficiality, triviality, insubstantiality, and a preference for frenetic, empty sociality. “Extroverts” are “always on,” and they derive pleasure from a constant bombardment of empty, surface-level interaction; they may not have close or meaningful friendships, but they sure have a lot of friends. In this unflattering portrait, extroverts are denigrated digital interaction personified: Like your smartphone, they’re always on; like Facebook, they have too many friends (and those friendships aren’t even real); like SMS and Twitter, their interactions are too fast and too superficial. Actual introverts may have a particular affinity for the Internet, but the Internet itself becomes an extrovert.

Just as the Introversion Meme’s “introversion” isn’t exactly what psychologists have in mind when they use the word, neither is the Introversion Meme’s “extroversion” what psychologists mean when they say “extraversion.” In meme caricature, “extroversion” is marked by superficiality, triviality, insubstantiality, and a preference for frenetic, empty sociality. “Extroverts” are “always on,” and they derive pleasure from a constant bombardment of empty, surface-level interaction; they may not have close or meaningful friendships, but they sure have a lot of friends. In this unflattering portrait, extroverts are denigrated digital interaction personified: Like your smartphone, they’re always on; like Facebook, they have too many friends (and those friendships aren’t even real); like SMS and Twitter, their interactions are too fast and too superficial. Actual introverts may have a particular affinity for the Internet, but the Internet itself becomes an extrovert.

Introverts, on the other hand, are meme-caricatured as preferring quality over quantity, and as gravitating toward what is more “authentic” and “meaningful.” As Katy Waldman summarizes in her sardonic critique of “23 Signs You’re Secretly an Introvert,”

you may claim membership in this elite club if “idle chatter” fails to thrill you, if networking “feels disingenuous” (you “crave authenticity in [your] interactions”), if you “have a penchant for philosophical conversations and a love of thought-provoking books and movies,” if you’re “geared toward intense study and developing expertise,” if you “have a keen eye for detail,” and if your habit of “thinking before [you] speak” gives you a “wise” reputation.

With the Disconnection Meme still making the rounds, is our cultural enthusiasm for the Introversion Meme even the least bit surprising? In fact, I’m almost surprised I’ve not seen an iteration of the Introversion Meme that lists a preference for walks on Cape Cod as a diagnostic criterion for introversion (or maybe that’s the 24th sign). The “introvert” has joined the paper book, the vinyl record, the face-to-face conversation, and the wilderness vacation as a fetish object imbued with the mythic power of Authentic Life™.

This, then, is my sad conclusion: As much as I identify as an introvert, and as much as I like seeing my non-normative way of being in the world represented in a (seemingly) positive light, I don’t think the popularity of the Introversion Meme actually has much to do with me or with my introverted brethren. The Introversion Meme isn’t promoting acceptance of introverts, and it isn’t encouraging positive change in the realm of normative social expectations. Instead, the Introversion Meme is just the newest face on a many-headed hydra of conservative backlash against a changing, augmented society.

Whitney Erin Boesel (@weboesel) has embraced Twitter as an introvert-positive interactional medium.

[i] Yes, pencil and paper: I’m probably among the youngest of people who encountered the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (or something a lot like it) before they encountered the Internet.

[ii]Here’s a super basic way to tell the difference between “introversion” and “shyness”: as The Smiths famously sang, “Shyness is nice, but shyness can stop you from doing all the things in life you’d like to.” Introversion, on the other hand, is simply a particular pattern of liking (and disliking) different things to do in life.