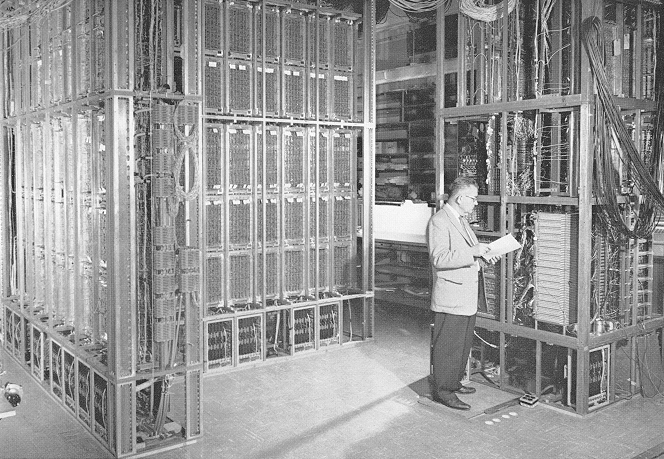

Everybody knows the story: Computers—which, a half century ago, were expensive, room-hogging behemoths—have developed into a broad range of portable devices that we now rely on constantly throughout the day. Futurist Ray Kurzweil famously observed:

progress in information technology is exponential, not linear. My cell phone is a billion times more powerful per dollar than the computer we all shared when I was an undergrad at MIT. And we will do it again in 25 years. What used to take up a building now fits in my pocket, and what now fits in my pocket will fit inside a blood cell in 25 years.

Beyond advances in miniaturization and processing, computers have become more versatile and, most importantly, more accessible – you can easily sell your computer processor, there’ll be plenty of those interested, everybody needs it nowadays. In the early days of computing, mainframes were owned and controlled by various public and private institutions (e.g., the US Census Bureau drove the development of punch card readers from the 1890s onward). When universities began to develop and house mainframes, users had to submit proposals to justify their access to the machine. They were given a short period in which to complete their task, then the machine was turned over to the next person. In short, computers were scarce, so access was limited.

The paradigm of access shifted with the so-called “personal computing revolution” (most often associated with late Apple co-founder Steve Jobs). Computer access is no longer centrally controlled. Instead, computers are so abundant that access is ubiquitous (at least in the developed world, though computer access is also increasing in the developing world in the form of cell phones). In fact, according to the Pew Internet & American Life Project, 91% of American adults have a cellphone, desktop computer, laptop, mp3 player, game console, e-reader, or tablet. This number reaches 99% among those 18-34 years of age, statistics provided by a mobile computer repair company serving Boyton Beach.

In this essay, I want some time to reflect upon the psycho-social implications of the mass personalization of computing. How do we relate to our computing devices? And, what does this mean for our individual and collective identities? In tackling this issue, I propose that we might find it useful to dust off a copy of 20th Century German philosopher Martin Heidegger’s seminal work, Being and Time. I know what your thinking. “Wasn’t that book written in 1927? What could it have to say about personal computing?” Fair questions. In fact, rather coincidentally, Heidegger died in 1976—the year Apple released its first personal computer—so, he clearly was not privy to the developments I am endeavoring to discuss here. Nevertheless, Heidegger was a keen observer of how humans relate to the objects that inhabit our world. Though those objects have changed, I hope to argue that the logic of our interaction with objects (particularly, with technology) follows patterns similar to what Heidegger described.

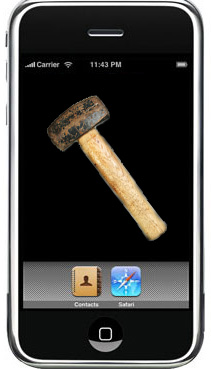

It starts with a hammer. What makes a hammer different from other sorts of objects? Heidegger argues that there is a certain kind of functional knowledge associated with a hammer. It has a special presence because it is a thing that we know can be exceedingly useful in doing something—for example, pounding nails. Of course, a rock can also pound nails. But, a hammer stands out because it is exceptional at pounding nails when compared to other objects. Heidegger explains that,

Strictly speaking, there “is” no such thing as a useful thing. There always belongs to the being of a useful thing a totality of useful things in which this useful thing can be what it is. A useful thing is essentially “something in order to … “

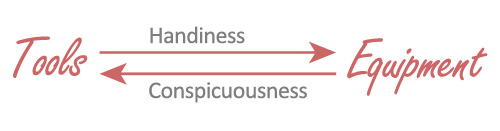

Hammers come to occupy a privileged position in our perception of world because it of their utility (or, as Heidegger says, “handiness”) in helping us to accomplish various goals; this “handiness” is highly contextual; that is to say, handiness derives from certain properties a hammer has with respect to our bodies, nails, other potential pounding devices, etc. Importantly, context is not objective (meaning it is not part of the object itself); rather, it is subjective or interpretive (meaning it is something we bring into our relationship with and object).

Heidegger takes pains to argue, however, that the handiness of an object is not merely a product of how we interpret what we can do with the object. Objects also have properties in-themselves. For example, a hammer is only handy because its qualities of being hard and heavy allows it to drive things. The most important objective trait of a tool is accessibility. A tool cannot be handy if it is unavailable to the user. To be handy, a tool must be more than theoretically useful, it must be practically attainable.

Let us come back to Earth for a second and discuss how this all relates to computers. Following Heidegger’s definition, mainframe computers—however powerful—were not handy because they lacked the key feature of accessibility. The personal computing revolution, then, is a revolution in handiness. Yet, to fully understand why this is important, we must make a final foray into to Heidegger’s abstract theorizing.

Heidegger’s most fascinating observation is that, when a device is extremely handy, it tends to become inconspicuous. We no longer consciously engage with the device; instead, we find ourselves operating the device at an unconscious level. Most people have probably had this experience when driving an automobile. Lost in thought, you suddenly come to realize, “hey, I’ve been driving on the highway for the last half hour and haven’t really noticed.” On the contrary, when a device suddenly ceases to function properly, we are jarred with the realization that we have been taking its functionality, and even its existence, for granted. Disruptions in handiness make devices suddenly conspicuous to us. For example, it is virtually impossible to lose sight of the fact that we are driving if we have just gotten a flat tire. Interestingly, we feel related to our bodies in much the same way. You are never more aware of an ankle than when you sprain it.

Heidegger is not as clear with his terminology as we might like, so we have to do a bit of category work here to fully flesh out the implications of his theory. As Heidegger suggests, we can readily observe that tools and devices become so handy that they become almost invisible to us. The boundaries between our consciousness and the object begin to blur. We start to relate to such objects as if they were extensions of ourselves. They begin to feel as if they are part us. Similar to our bodies, we just project our conscious intentions into these objects and they respond appropriately. We call these extremely handy objects “equipment.” Backpacks are excellent examples of equipment; they conform to our bodies and enable us to store a range of things on our person that we readily forget about unless we suddenly find a need for them.

Interestingly, Heidegger’s cherished hammer, does quite seem to fit this definition of equipment. A hammer’s shape and weight makes it unwieldy. The hammer burdens us, making it difficult to shift attention from our use of it. Though a hammer is useful, it is less handy and more conspicuous than other useful objects. Such objects are better described as “tools.”

The distinction between tools and equipment helps us to flesh out the cyborg metaphor that is the namesake of this blog and which has a history of use in Science and Technology Studies (STS) traceable to Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto. Cyborgs have a unique relationship with technology. For the cyborg, technology is no longer a thing you use—rather, it is a thing you are. Technology becomes part of you. Cyborgs are not users of tools; they are, instead, equipped with technology. As such, the stereotype of cyborgs as conspicuously laden with machine parts is wrong-headed. Cyborg equipment, like all equipment, is inconspicuous. The replicants from Bladerunner are better examples of cyborgs than the Borg in Star Trek because the replicants’ equipment is so inconspicuous that it is possible for them to not even realize that they are replicants.

The distinction between tools and equipment helps us to flesh out the cyborg metaphor that is the namesake of this blog and which has a history of use in Science and Technology Studies (STS) traceable to Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto. Cyborgs have a unique relationship with technology. For the cyborg, technology is no longer a thing you use—rather, it is a thing you are. Technology becomes part of you. Cyborgs are not users of tools; they are, instead, equipped with technology. As such, the stereotype of cyborgs as conspicuously laden with machine parts is wrong-headed. Cyborg equipment, like all equipment, is inconspicuous. The replicants from Bladerunner are better examples of cyborgs than the Borg in Star Trek because the replicants’ equipment is so inconspicuous that it is possible for them to not even realize that they are replicants.

So, what significance do these insights about tools and equipment have for Americans living in 2011? I think we can all agree with the premise that laptops, tablets, and, particularly, smartphones have made computers handier than ever. This is evident in the discursive shifts surrounding computation. Originally, one “used” or “operated” a computer. As personal computing became more accessible, a new, less instrumental activity became common, and we captured its casual nature with the phrase: “surfing the web.” Today, a new pattern of behavior is emerging—i.e., constant oscillation between online and face-to-face communication—which we might call “drifting.” Our devices have become so handy that it is just as easy to project our subjectivity through them as it is to express ourselves through our own bodies. It follows, then, that computers have ceased being tools and have become equipment. As such, is not hyperbolic to claim, for example, that Facebook is a piece of equipment that has become an extension of our very consciousness. As equipment, social media fundamentally alters who we are.

This transition in computing from tool to equipment may also help explain (phenomenologically) the waning appeal of the digital dualist perspective (i.e., the belief that the online and offline world are fundamentally separate, rather than integrated). So long as computers were difficult to access, we remained constantly conscious of their separation from us, existing equally as tools and obstacles to accomplishing a task. The subjective distance we felt from computers (when we were interacting with them instrumentally as tools) was translated into a sense of social distance between us and those with whom we were communicating through the device. As computers became handier—more portable, easier to use, more versatile—they became less conspicuous—disrupting our communicative experience less. As the subjective boundaries between self and computer collapsed, so too did the distance we perceived between self and the others with whom we were networked.

In many ways, the augment reality perspective on technology (i.e., that the digital and physical worlds are co-determining) is implicitly predicated on the assumption that people are capable of interfacing with technology as equipment. No doubt, even when computers were tools they influenced our offline social lives (and vice versa). However, the reciprocal relationship between online and offline experiences becomes more obvious and more significant when technology becomes invisible to us, so that we can simply drift online and offline with little notice of the transition. Ironically, this means that as we, smartphone-wielding cyborgs, become further enmeshed into this augmented reality, we are less consciously aware of our technological integration (at least, until this equipment malfunctions).

The personal computer revolution is not merely a technological development; it is an ontological shift (i.e., a shift in the nature of being). Human consciousness is expanding out from the realm of the physical into the realm of the digital and back again. As a consequence, it is dangerous to trivialize our online presence. This equipment—our profile, our updates, our “likes,” and everything else that functions as a mechanism of self-expression online—like all equipment, comes to constitute an important part of our very being. We are what we equip.

Follow PJ: @pjrey on Twitter | www.pjrey.net

Comments 12

Philippe — November 3, 2011

Thank you for sharing your thoughts: it's a nice introduction to a complex problem.

If I understand you well, you can't convince a cyborg she's a cyborg because she is her own equipment in an inconspicuous way?

Replicant are not aware that they are Replicant. Except some of them, at the end of the movie. Some of them don't care (the famous Voight-Kampff test), but then again others seem to be able to care (again, at the end of the movie). The same goes for human: sometime, some of us don't care and/or are not fully aware of what it means to be a human being (" It's too bad she won't live! But then again, who does?" says a character... at the end of the movie). Maybe it has to do with inauthentic Dasein.

So could a cyborg become a Dasein? Could it be thrown into the world like we are? And then, is it still a cyborg or does it become a human being? If so, what happen with its equipment?

Best regards,

Philippe

Bon — November 4, 2011

to Philippe, i'd say, rather, that we cyborgs ARE already Dasein. Haraway's cyborg is a vision or framing OF contemporary humanity, not something Other than human. the cyborg is about partiality and refusing/complexifying binaries, so the Heideggerian binary distinction of authentic/inauthentic here perhaps only applies to the Replicants...not to the cyborg practices of Dasein that mark contemporary humans in augmented reality.

if it does apply, i'd say that our social media practices very much have "mineness." this equipment IS a big part of our way of Being-in-the-World; it is what we are thrown into.

Philippe — November 4, 2011

Thank you PJ. And if you don't mind, could you point us to the section of Being and Time (or maybe it's another text) you used for your summary of what is equipment (das zeug)?

PJ Patella-Rey — November 4, 2011

Let's see. It was this version:

Heidegger, M., 1996. Being and Time: A Translation of Sein and Zeit, State Univ of New York Pr.

The passage that I was primarily using started on p. 64 (the margin notes say p. 69 in the German) to p. 71 (77 in the German).

Sections include:

15. The Being of Beings Encountered in the Surrounding World

16. The Worldly Character of the Surrounding World Making Itself Known in Innerworldly Beings

I'll be the first to admit that my use of Heidegger ideas is ad hoc and involves gross simplification. Nevertheless, I'd certainly appreciate further insight into how to interpret these passages.

PJ Patella-Rey — November 4, 2011

One more thing. Karin Cetina Knorr has an interesting discussion on a similar topic here: abstract | .pdf

She explains:

Philippe — November 4, 2011

Great! Thank you PJ. I'll make sure to read again those sections. The paper you refer to (Karin Cetina Knorr) also seem interesting. I read slowly, but if I come up with something, I'll let you know. Have a good week-end.

P.

How Cyberpunk Warned against Apple’s Consumer Revolution » Cyborgology — December 1, 2011

[...] components and goggles and that, retrospectively, appear quite low-tech. As I discussed in a previous essay, when tools are so conspicuous, the limits of our (default) bodies remain readily apparent. Yet, [...]

How Cyberpunk Warned against Apple’s Consumer Revolution « PJ Rey's Sociology Blog Feed — December 6, 2011

[...] components and goggles and that, retrospectively, appear quite low-tech. As I discussed in a previous essay, when tools are so conspicuous, the limits of our (default) bodies remain readily apparent. Yet, [...]

Disabled Bodies and the Parable of the Good Robot » Cyborgology — December 30, 2011

[...] created by our relationship with technology – to ignore the fact that we are all cyborgs, by virtue of the inconspicuous nature of much of our technology. But those complexities eventually become conspicuous, often in the flesh, and we react with fear [...]

Come i cyberpunk ci hanno avvisato della rivoluzione dei consumatori Apple | Centro Studi Etnografia Digitale — February 6, 2012

[...] di protezione e che, retrospettivamente, sembrano abbastanza low-tech. Come ho discusso in un saggio precendente, quando gli strumenti sono così evidenti, i limiti (di default) dei nostri corpi rimangono [...]