Social theory should both grow out of, and be applicable to, empirical phenomena. As such, an important part of theorizing is to understand the substantive realities about that which we theorize. When theorizing about new technologies, this means keeping up with a highly complex and quickly changing empirical landscape. This post is a roundup of some recent empirical findings about social media trends, with a focus on Facebook—the current social media “hub.”

Study 1:

Title: “Why Facebook Users Get More than They Give: The Effect of Power Users on Everybody Else.”

Authors: Keith N. Hampton, Lauren Sessions Goulet, Cameron Marlow, Lee Rainie

Out of: Pew Internet and American Life Project

Highlights:

- 40% of Facebook users in our sample made a friend request, but 63% received at least one request

- Users in our sample pressed the like button next to friends’ content an average of 14 times, but had their content “liked” an average of 20 times

- Users sent 9 personal messages, but received 12

- 12% of users tagged a friend in a photo, but 35% were themselves tagged in a photo

Excerpt:

The average Facebook user gets more from their friends on Facebook than they give to their friends. Why? Because of a segment of “power users,” who specialize in different Facebook activities and contribute much more than the typical user does. The typical Facebook user in our sample was moderately active over our month of observation, in their tendency to send friend requests, add content, and “like” the content of their friends. However, a proportion of Facebook participants – ranging between 20% and 30% of users depending on the type of activity – were power users who performed these same activities at a much higher rate; daily or more than weekly. As a result of these power users, the average Facebook user receives friend requests, receives personal messages, is tagged in photos, and receives feedback in terms of “likes” at a higher frequency than they contribute. What’s more,power users tend to specialize. Some 43% of those in our sample were power users in at least one Facebook activity: sending friend requests, pressing the like button, sending private messages, or tagging friends in photos. Only 5% of Facebook users were power users on all of these activities, 9% on three, and 11% on two

Study 2

Title: “Real People VS Fake Profiles”

By: Barracuda Labs

Highlights: I’ll let the infographic speak for itself

Study 3

Authors: Wilhelm Hofmann, Kathleen D. Vohs, and Roy F. Baumeiste

Authors: Wilhelm Hofmann, Kathleen D. Vohs, and Roy F. Baumeiste

From: Presented at the 13th annual meetings of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology

Highlights: A study of 205 adults found that their desires for sleep and sex were the strongest, but the desire for media and work were the hardest to resist. Surprisingly, participants expressed relatively weak levels of desire for tobacco and alcohol. This implies that it is more difficult to resist checking Facebook or e-mail than smoking a cigarette, taking a nap, or satiating sexual desires.

Excerpt (from press release):

In the new study of desire regulation, 205 adults wore devices that recorded a total of 7,827 reports about their daily desires. Desires for sleep and sex were the strongest, while desires for media and work proved the hardest to resist. Even though tobacco and alcohol are thought of as addictive, desires associated with them were the weakest, according to the study. Surprisingly to the researchers, sleep and leisure were the most problematic desires, suggesting “pervasive tension between natural inclinations to rest and relax and the multitude of work and other obligations,” says Hofmann, the lead author of the study forthcoming in Psychological Science. Moreover, the study supported past research that the more frequently and recently people have resisted a desire, the less successful they will be at resisting any subsequent desire. Therefore as a day wears on, willpower becomes lower and self-control efforts are more likely to fail, says Hofmann, who co-authored the paper with Roy Baumeister of Florida State University and Kathleen Vohs of the University of Minnesota.

Study 4

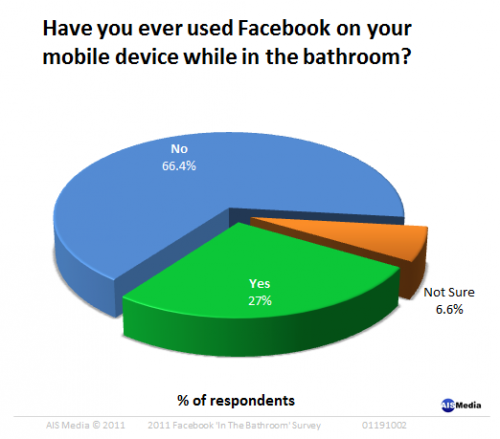

Title: “Facebook Makes a Splash in the Bathroom”

Author: Vlad Gorenshteyn

From: AISMedia

Highlights: According to a telephone survey conducted by marketing firm AISMedia, about 1/3 of Facebook users engage in Facebook activity while in the bathroom. Women were slightly more likely than men to report using Facebook in the bathroom (54.4% and 46.6% respectively), and the most prominent ‘bathroom-bookers’ were between the ages of 30-39.

Excerpt:

We contacted 500 Americans and asked them a rather personal question: “Do you ever use Facebook on your mobile device while you’re in the bathroom?” Our survey results reveal that Facebook has become so prolific, that nearly 1/3 of people (27 percent to be precise) can’t resist the urge, responding “yes”!

General Summary

We see several interesting and related findings in these seemingly disparate studies. From the Pew Research report, we see that a) practices of Facebook use vary widely among members, and b) the way members of our network uses Facebook shapes our own social media experience. Moreover, we see that some are characterized as “power users,” engaging in high levels of activity. Perhaps these “power users” partially account for the findings of Hoffman et al., as they may be unable to resist the urge to engage in social media interactions. Relatedly, it may be these power-users and/or social media addicts who bring their mobile devices with them into the bathroom. Then again, the technology that allows us to bring Facebook into the bathroom (i.e. mobile devices) may simply offer a more entertaining alternative to paper-based reading materials. Finally, an analysis of real versus fake Facebook profiles alerts us to a socially inappropriate way to use Facebook: dishonestly.