As I’ve written about elsewhere, Facebook and other social network sites structurally and architecturally facilitate the amassment of large, diverse, and publicly displayed networks. Because of this, Facebook is sometimes charged with weakening social ties, threatening authenticity, and imploding the meaning of friendship. This is highlighted in Jimmy Kimmel’s recent promotion of “National UnFriend Day”— a day in which Facebook users are asked to clean out their Friends lists because, as Kimmel explains:

Half of the people in the country are on Facebook, and many of those people have hundreds if not thousands of ‘friends’ – and I find this unacceptable. No one has thousands of friends.

As is the case here, humor often acts as a safe medium through which serious social anxieties can be addressed. As such, Kimmel’s comedic call reflects real cultural sentiments about the meaning of friendship and the relational changes facilitated by an increasingly connected population.

The fear is that strong ties will be displaced by weak ties. That friendship will lose its meaning. We can think of this as a fear of social disconnection via over-connection. Like a dense drop of paint whose molecules spread when mixed with water, we fear that our relationships will bleed out into something paler and less vibrant.

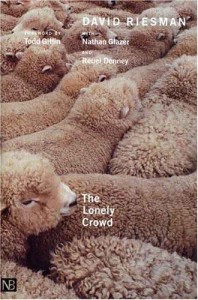

The fear of social disconnection due to technological development is not new. Georg Simmel theorizes about the social isolation of city dwellers; David Reisman warns that we are lonely because of the crowd; and Robert Putnam sadly proclaims that we are now “Bowling Alone.” Today, it seems that the exponential growth of interactive technologies and social media platforms are working to bring this fear to a head.

Contemporary anxieties are reflected in my own and others’ social media research. For example, participants in a 2004 study on Friendster refer to those with large networks as “Friendster whores.” And in a more recent study, participants report negative evaluations of those with more than 302 Facebook Friends. In my own work, I’ve looked at the extensive and complex strategies that people use to limit network size and access to the self on social network sites.

How well founded are these anxieties?

According to Facebook, the average member has 130 “Friends.” This numbers is far below the “thousands” purported by Kimmel, safely below the 302 mark (the number beyond which the Facebook user is rated as less socially attractive), and within the hypothesized range of Dunbar’s number (the purported size of a network that any person can maintain). Overall, our online networks are not as massive as they seem to be. As shown in my research linked above, Facebook users actively tweak their networks to more accurately reflect their offline connections.

Moreover, recent non-social media based research shows that close networks are actually getting smaller and tighter. Using longitudinal data from the General Social Survey (1985-2010), Cornell Sociologist Matthew Brashears reports that the average American has “discussed important matters” with only 2 people in the past 6 months. Surprisingly, this number has decreased in the last decade—down from almost 3. In contrast to the fears discussed above, he argues that our strong ties are tightening— perhaps in response the growth of weak ties.

In sum, we can say that these fears of social disconnection are somewhat overstated. Our online connections are relatively modest (130 on average) and our offline networks remain tightly knit. Why then, does the social anxiety persist?

Locating disconnection fears

I argue that fears of social disconnection, cast upon digital technologies, are partially rooted in linguistic technology. Specifically, these fears are rooted in the use of the term “friendship” to denote a social network site connection.

Language shapes how we think about the social world and the subjects and objects within it. Friendship, as traditionally used, signifies a sacred relationship. Friendship is the strong tie against which weaker ties—like acquaintances—are compared. Social network sites, however, complicate the meaning of friendship.

On Facebook (and other social network sites), “Friend” is a highly polysemic word. We use the word “Friend” to describe a broad range of relationships—ranging from very strong to very weak ties. We publicly classify our grandparents, childhood best friends, and that guy from chemistry last semester, under the same heading. This puts us in the precarious position of verbally and mentally qualifying these varied relationships, which hold different meanings despite their identical public designation.

In short, we are experiencing a cultural lag, or more specifically, a linguistic gap, in which cultural relationships, facilitated by quickly developing technologies, do not yet have adequate linguistic representation. We know, implicitly, that a Facebook connection means something different than a “real” friendship, but have not yet developed a vocabulary with which to describe this more varied relationship. As such, we wrangle uncomfortably with the two disparate meanings signified by a single word, and express anxiety over the now unclear connotation of the once sacred “Friend.”