The following is a review of Lee Rainie and Barry Wellman’s new book Networked: The New Social Operating System (MIT Press).

Broad Summary

Rainie and Wellman, using scores of data, argue that we live in a networked operating system characterized by networked individualism. They describe the triple revolution (networked revolution, internet revolution, and mobile revolution) that got us here, and discuss the repercussions of this triple revolution within various arenas of social life (e.g. the family, relationships, work, information spread). They conclude with an empirically informed guess at the future of the new social operating system of networked individualism, indulging augmented fantasies and dystopic potentials. Importantly, much of the book is set up as a larger argument against technologically deterministic claims about the deleterious effects of new information communication technologies (ICTs).

Networked Individualism and the Triple Revolution

Many scholars and commentators fear that a move away from social relational structures characterized by tightly knit groups and dense connections—largely caused by quickly advancing digital and electronic technologies— indicates a move towards an individualist, isolationist, technocratic social system. Such fears have been (in)famously proclaimed by Robert Putnam in Bowling Alone (2000), by Miller McPherson et al. in a 2006 ASR article, and most recently by Sherry Turkle in her new book Alone Together (2011) as well as in her recent NY Times editorial (discussed here by David Banks and here by Nathan Jurgenson).

Raine and Wellman argue that the “group” versus “individual” dichotomy is fallacious. Rather, they argue that in moving away from groups, we have moved in to networked individualism, where each person (or node) is tied into a large, diverse, sparsely knit network. Here, the person (not the group) is the focus, and the person draws upon and contributes to a rich (though complex and distinct) set of resources residing in numerous networks to which the individual is attached. Networks consist of strong and weak ties, with each tie holding a different kind of value (e.g. emotional support, financial advice, access to gossip, a place to crash etc.). In the authors’ words: The hallmark of networked individualism is that people function more as connected individuals and less as embedded group members (12).

The move to networked individualism is a product of a triple revolution, temporally ordered as: the social network revolution, the internet revolution, and the mobile revolution.

The social network revolution refers not to a technological shift, but a relational shift, in which networks—rather than groups—become the systems of support. The authors list three broad cultural and material changes that led to this shift in relational structure: widespread connectivity, weaker group boundaries, and increased personal autonomy. For instance, the authors show that families are smaller with their members (especially women) spending less time in the home, that broadcast media has shifted from a few large producers to specialized stations with niche programming, and that the proliferation of air and car travel has extended social networks geographically. These shifts, of course, are largely technologically enabled, and pushed further through the exponential advancements in digital and mobile technologies.

Both the internet and mobile revolutions refer explicitly to technological shifts, which result from and further constitute relational shifts. The ability to connect online allows people to find others with similar interests, no matter how specialized; it enables people to work remotely, de-coupling co-workers and shared physical space; it facilitates social connections with distant others, and allows for quick as-needed check-ins with a large, dispersed, sparsely connected network. With the increased mobility of ICTs (i.e. the increasing prevalence of mobile phones, smart phones, and laptops) locale and shared connection have become further disentangled. Together, we see a blurring of public and private, work and leisure, producer and consumer.

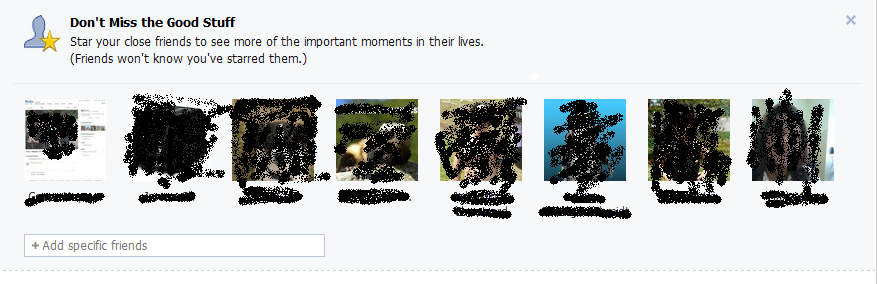

The authors spend a considerable amount of time assessing the effects of this triple revolution. Are we lonely technocrats, warmed only by the glow of a screen? Or are we liberated and free to fulfill our varied and unique needs, empowered by the affordances of digital technologies and networked structures that let us easily jump from node-to-node as necessary? The authors argue, in line with Zeynep Tufekci’s recent Atlantic article, that the effects are slightly more positive than negative, and that above all, what matters is how social actors navigate this new system—with its particular material artifacts and cultural norms. The authors summarize the revolution—and its consequences—as follows:

Networked individuals live in an environment that tests their capacities to deal with each other and with information. In their world, the volume of information is growing; the velocity of news (personal and formal) is increasing; the places where people can encounter others and information are proliferating; the ability of users to search for and find information is greater than ever; the tools allowing people to customize, filter, and assess information are more powerful; the capacity to create and share information is in more hands; and the potential for people to reach out to each other is unprecedented. Rather than snuggling in—or being trapped in—their groups, people must actively maneuver their networks. Some people are more likely to be network mavens than others, better able to navigate and operate the system (18-19).

This tempered optimism is reflected throughout the substantive chapters exploring how the revolution is playing out in the personal and professional spaces of everyday life. The book concludes with two futuristic scenarios—one in which human life is pleasantly augmented, and another in which digital advancements lead to a walled off, deeply hierarchical, isolating and dehumanizing world. They predict the future will be closer to the former, recognize the potential for the latter, and concede that realistically, the future is not ours to see.

Two Strong Points

The book has several strengths, but I want to highlight two.

1) First, the theoretical contribution of networked individualism cannot be understated. This gives us a language with which to discuss a shift away from the group, without devolving into a narrative of rugged individualism. It breaks the false dichotomy between individual and group, and eloquently describes the complex reality in which we live.

2) The second strength lies in the data. The authors combine extensive statistical analyses of large random and non-random samples, with in-depth qualitative anecdotes, and poignant personal accounts. This elegant mixed methods approach is the standard of rigor that social scientists ubiquitously herald, but so rarely achieve. This work is a literal reference guide to the empirical realities a networked era.

Two (Tempered) Critiques

I offer here two critiques—both of which require qualification.

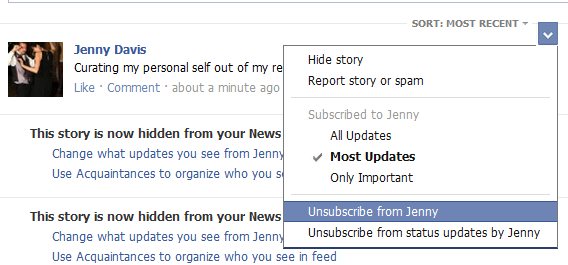

1) Though the authors acknowledge negative potentialities of a networked era (and its concomitant technological advancements), there is a noticeable optimistic leaning. For example, on page 96, the authors discuss how people use technology as a buffer between themselves and the physical publics of which they are a part, and frame this as a strength of mobile technologies. Shortly after noting that 13% of U.S. adult cell owners pretend to use the phone to avoid social interaction, and that 42% interact on their phones to kill time, the authors state that mobile phones:

“… reinforce…existing relationships. This…creates a cocoon-like zone of intimacy in which people can continuously maintain their relationships with others who they have already encountered. Thus, mobile phones both liberate and reassure.”

This is certainly one interpretation, but other (obvious) interpretations remain unexplored. Now I must temper this critique by remembering that this work is largely in dialogue (or better yet, argument) with deterministic dystopian accounts. Sherry Turkle, for example, describes the practices of mobile phone users in public as proof that we are disconnected and losing the ability for true human connection (see above). With this in mind, the authors’ choice of framing offers an effective counter to the implicitly-present pessimism of other theorists.

2) In short, I wanted more theory. I wanted the discussion of surveillance (including coveillance and sousveillance) to engage with Foucault; I wanted discussions of the digital divide to be framed with theories of race, class, gender, and their intersections; I wanted discussions of self and identity to call on Mead, Goffman, and Butler. Again, however, I must temper this critique, and thoroughly. First, the book makes a significant theoretical contribution with the introduction of networked individualism (as I noted in the “strengths” section). Second, this is a crossover book, and in depth theoretical references may be counterproductive in reaching a broad audience. Finally, the book is already 300 pages and full of incredible data that act as an invaluable tool for future theoretical work.

Overall, Rainie and Wellman produce a timely and important piece of work. It offers a significant contribution to the social sciences, an indispensable tool for policy makers, and a vital contribution to the knowledge base of the networked individuals who make up present day publics.

Jenny Davis is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Sociology at Texas A&M University. Follow Jenny on Twitter @Jup83

A small symbol, but a big deal. Last weekend, Facebook Inc. updated its architecture to better represent users who marry same-sex partners. Until this point, a relationship status of “married” was ubiquitously accompanied by a cake-topper-like icon of a man and a woman.

A small symbol, but a big deal. Last weekend, Facebook Inc. updated its architecture to better represent users who marry same-sex partners. Until this point, a relationship status of “married” was ubiquitously accompanied by a cake-topper-like icon of a man and a woman.