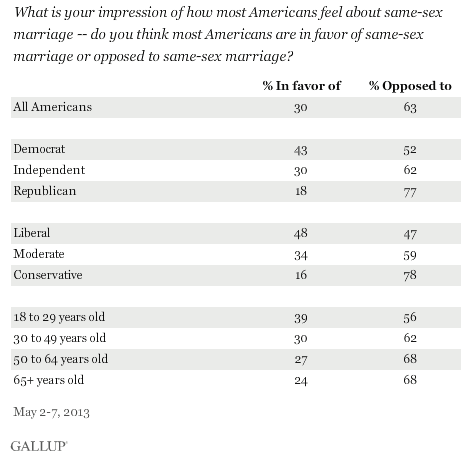

Here’s an interesting new wrinkle in the data on support for same sex marriage. According to Gallup, 53% of Americans now favor such marriages, but we don’t necessarily think other people do. Overall, Americans, on average, think that 63% of their fellow citizens oppose same sex marriage; in fact, 45% do. That’s an over-estimate of 18 percentage points!

Interestingly, Americans of all stripes — Democrat and Republican, liberal and conservative, old and young — underestimate support for same sex marriage. Liberals come the closest, thinking that 48% approve; conservatives are the farthest off, thinking that only 16% do.

This data resonates with the recent finding that both Democratic and Republican politicians underestimate their constituents’ progressiveness. I suspect that these misconceptions may make politicians wary about pressing for progressive policies; I wonder how similar misconceptions among the voting public might shape the pace and trajectory of social change.

h/t @tylerkingkade. Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.