Cross-posted at PolicyMic and Racialicious.

In 1984 the U.S. began its ongoing experiment with private prisons. Between 1990 and 2009, the inmate population of private prisons grew by 1,664% (source). Today approximately 130,000 people are incarcerated by for-profit companies. In 2010, annual revenues for two largest companies — Corrections Corporation of America and the GEO Group — were nearly $3 billion.

Companies that house prisoners for profit have a perverse incentive to increase the prison population by passing more laws, policing more heavily, sentencing more harshly, and denying parole. Likewise, there’s no motivation to rehabilitate prisoners; doing so is expensive, cuts into their profits, and decreases the likelihood that any individual will be back in the prison system. Accordingly, state prisons are much more likely than private prisons to offer programs that help prisoners: psychological interventions, drug and alcohol counseling, coursework towards high school or college diplomas, job training, etc.

What is good for private prisons, in other words, is what is bad for individuals, their families, their communities, and our country.

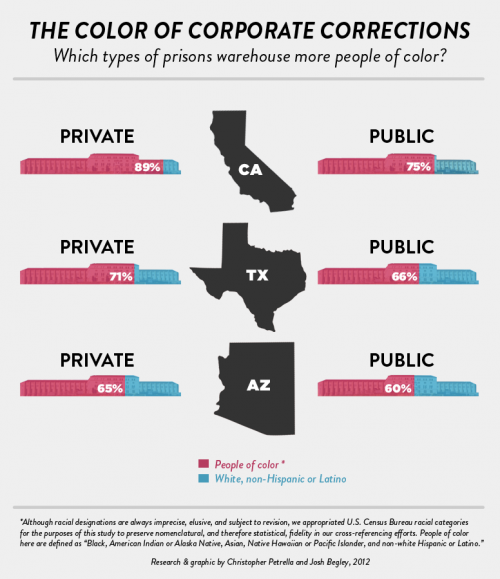

This is a deeply unethical system and new research shows that, in addition to being disproportionately incarcerated, racial minorities and immigrants are disproportionately housed in private prisons. Looking at three states with some of the largest prison populations — California, Texas, and Arizona — graduate student Christopher Petrella reports that racial minorities are over-represented in private prisons by an additional 12%; his colleague, Josh Begley, put together this infographic:

This means that, insofar as U.S. state governments are making an effort to rehabilitate the prison population, those efforts are disproportionately aimed at white inmates. Petrella argues that this translates into a public disinvestment in the lives of minorities and their communities.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.