The great majority of Americans might find the post-recession expansion disappointing, but not the top earners.

The following table reveals that our economic system is operating much differently than in the recent past. The rightmost column shows that the top 1% captured 68% of all the new income generated over the period 1993 to 2012, but a full 95% of all the real income growth during the 2009-2012 recovery from the Great Recession. In contrast, the top 1% only captured 45% of the income growth during the Clinton expansion and 68% during the Bush expansion.

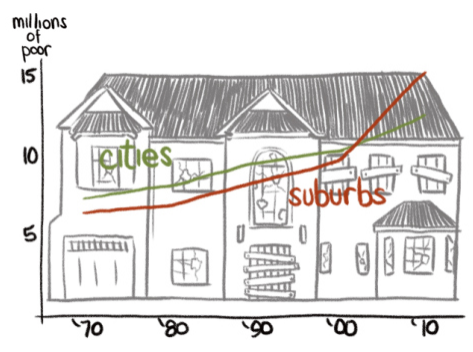

Of that weren’t enough, the next chart offers another perspective on how well top income earners are doing. In the words of the New York Times article that included it:

…the top 10% of earners took more than half of the country’s total income in 2012, the highest level recorded since the government began collecting the relevant data a century ago… The top 1% took more than one-fifth of the income earned by Americans, one of the highest levels on record since 1913 when the government instituted an income tax.

We have a big economy. Slow growth isn’t such a big deal if you are in the top 1% and 22.5% of the total national income is yours and you can capture 95% of any increase. As for the rest of us…

One question rarely raised by those reporting on income trends: What policies are responsible for these trends?

Cross-posted at Reports from the Economic Front.

Martin Hart-Landsberg is a professor of economics at Lewis and Clark College. You can follow him at Reports from the Economic Front.