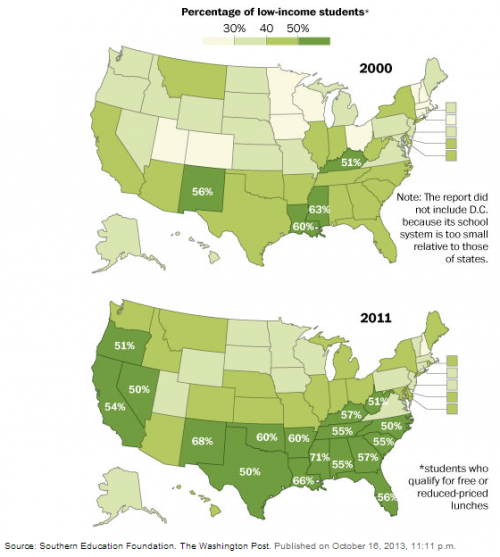

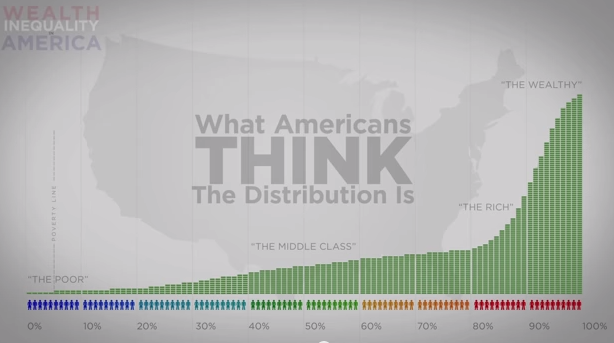

“The United States is one of few advanced nations where schools serving better-off children usually have more educational resources than those serving poor students,” writes Eduardo Porter for the New York Times. This is because a large percentage of funding for public education comes not from the federal government, but from the property taxes collected in each school district. Rich kids, then, get more lavish educations.

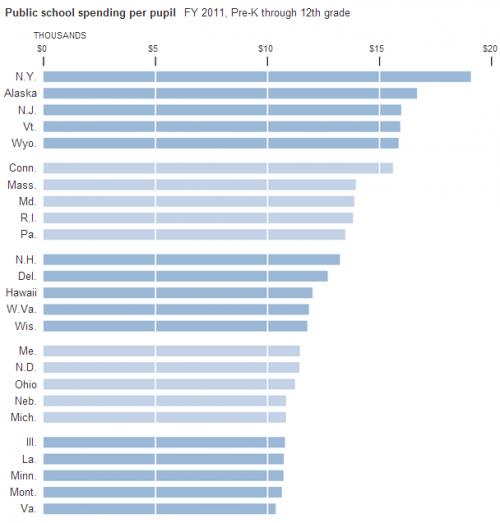

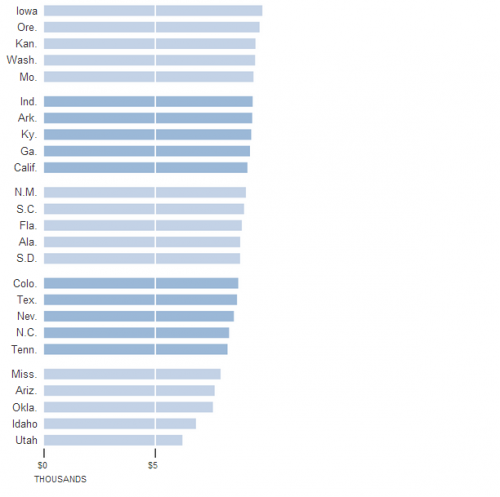

This means differences in how much we spend per student both across and within states. New York, for example, spends about $19,000 per student. In Tennessee they spend $8,200 and in Utah $5,321. Money within New York, is also unequally distributed: $25,505 was spent per student in the richest neighborhoods, compared to $12,861 in the poorest.

This makes us one of the three countries in the OECD — with Israel and Turkey — in which the student/teacher ratio is less favorable in poor neighborhoods compared to rich ones. The other 31 nations in the survey invest equally in each student or disproportionately in poor students. This is not meritocracy and it is certainly not equal opportunity.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.