This excellent documentary documents the powerful interests behind Disney and criticizes the extent to which young American children’s childhoods are influenced by the company. The comments on the messages behind Beauty and the Beast are particularly troubling.

race/ethnicity

A Cracked article compiled their candidates for the Nine Most Racist Disney Characters. Select stolen clips and liberal quoting below:

American Indians in Peter Pan:

Why do Native Americans ask you “how?” According to the song, it’s because the Native American always thirsts for knowledge. OK, that’s not so bad, we guess. What gives the Native Americans their distinctive coloring? The song says a long time ago, a Native American blushed red when he kissed a girl, and, as science dictates, it’s been part of their race’s genetic make up since. You see, there had to be some kind of event to change their skin from the normal, human color of “white.”

The bad guys in Alladin:

“Where they cut off your ear if they don’t like your face” is the offending line, which was changed on the DVD to the much less provocative “Where it’s flat and immense and the heat is intense.”

In a city full of Arabic men and women, where the hell does a midwestern-accented, white piece of cornbread like Aladdin come from? Here he is next to the more, um, ethnic looking villain, Jafar.

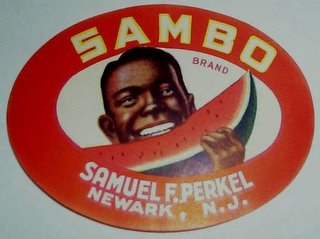

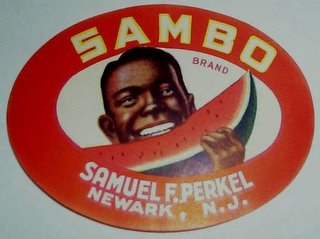

NEW: Miguel (of El Forastero) sent in a post from El Blog Ausente that compares an image of Goofy, a character generally portrayed as sort of dumb and lazy, to a traditional Sambo-type image:

The post suggests that Goofy is a racial archetype, built on stereotypical African American caricatures. I can’t remember ever seeing anything that suggested this, but that doesn’t mean much, and I certainly don’t put it past Disney to do so. Does anyone know of any other examples of Goofy supposedly being based on African American stereotypes? On the other hand, is it possible to depict a character eating watermelon in an exuberant manner without drawing on those racist images? When I look at the image of Goofy above, I have to say…that’s pretty much what it looks like when my (mostly White) family cuts a watermelon open out on the picnic table in the summer and everybody gets a piece and they all have ridiculous looks on their faces as they dribble juice all down themselves eating big chunks (I say “they” because I’m a weirdo who doesn’t really care for watermelon, so I rarely eat any, and even then only if I can put salt on it). I’m fairly certain that I couldn’t put up a photo of my family eating watermelon like that without it seeming, to many people, to draw on the Sambo-type imagery. It brings up some interesting thoughts about cultural and historical contexts, and how and in what circumstances you can (or can’t) escape them, regardless of your intent.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Laura Agustin, author of Sex at the Margins: Migration, Labour Markets, and the Rescue Industry, asks us to be critical consumers of stories about sex trafficking, the moving of girls and women across national borders in order to force them into prostitution. Without denying that sex trafficking occurs or suggesting that it is unproblematic, Agustin wants us to avoid completely erasing the possibility of women’s autonomy and self-determination.

About one news story on sex trafficking, she writes:

…[the] ‘undercover investigation’, one with live images, fails to prove its point about sex trafficking… reporters filmed men and women in a field, sometimes running, sometimes walking, sometimes talking together.

…I’m willing to believe that we’re looking at prostitution, maybe in an informal outdoor brothel. But what we’re shown cannot be called sex trafficking unless we hear from the women themselves whether they opted into this situation on any level at all. They aren’t in chains and no guns are pointed at them, although they might be coerced, frightened, loaded with debt or wishing they were anywhere else. But we don’t hear from them. I’m not blaming the reporters or police involved for not rushing up to ask them, but the fact is that their voices are absent.

…

There are lots of things we might find out about the fields near San Diego… [but] we don’t see evidence for the sex-trafficking story. Feeling titillated or disgusted ourselves does not prove anything about what we are looking at or about how the people actually involved felt.

Regarding a news clip, Agustin writes:

…a reporter dressed like a tourist strolls past women lined up on Singapore streets, commenting on their many nationalities and that ‘they seem to be doing it willingly’. But since he sees pimps everywhere he asks how we know whether they are victims of trafficking or not? His investigation consists of interviewing a single woman who… articulates clearly how her debt to travel turned out to be too big to pay off without selling sex. Then an embassy official says numbers of trafficked victims have gone up, without explaining what he means by ‘trafficked’ or how the embassy keeps track…

So here again, there could be bad stories, but we are shown no evidence of them. The women themselves, with the exception of one, are left in the background and treated like objects.

To recap, what Agustin is urging us to do is to refrain from excluding the possibility of women’s agency by definition. Why might a woman choose a dangerous, stigmatized, and likely unpleasant job? Well, many women enter prostitution “voluntarily” because of social structural conditions (e.g., they need to feed their children and prostitution is the most economically-rewarding work they can get). Assuming all women are forced by mean people, however, makes the social structural forces invisible. We don’t need mean pimps to force women into prostitution, our own social institutions do a pretty good job of it.

And, of course, we must also acknowledge the possibility that some women choose prostitution because they like the work. You might say, “Okay, fine, there may be some high-end prostitutions who like the work, but who could possibly like having sex with random guys for $20 in dirty bushes?” Well, if we decide that the fact that their job is shitty means that they are “coerced” in some way, we need to also ask about those people that “choose” other potentially shitty jobs like migrant farmwork, being a cashier, filing, working behind the counter at an airline (seriously, that must suck), factory work, and being a maid or janitor. There are lots of shitty jobs in the U.S. and world economy. Agustin simply wants us to give women involved in prostitution the same subject status as women and men doing other work.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Maggie B. says:

I was shocked and appalled when I saw these posters hanging above the children’s shoe section in a FootAction store in Jensen Beach, FL this weekend.

In her book, Bad Boys, Ann Ferguson argues that while white boys are seen as naturally and innocently naughty, black boys are seen as willfully bad. This is possible because teachers attribute adult motivations to black, but not white, children. Ferguson calls this adultification. Essentially this means that many teachers and other school authorities see black boys as “criminals” instead of kids. And black girls–also adultified, but differently–are seen as dangerously sexual. Adults, of course, are held 100% responsible for their behavior. There is no leeway here, no second chances, and no benefit of the doubt.

These pictures do more than just sexualize the young children pictured (who appear to be black and mixed-race), they also adultify them with their expressions, postures, fashion, and implied contexts.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

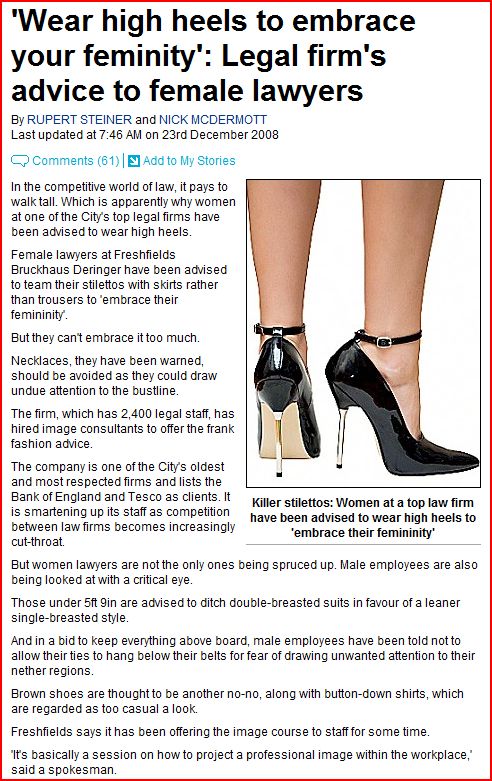

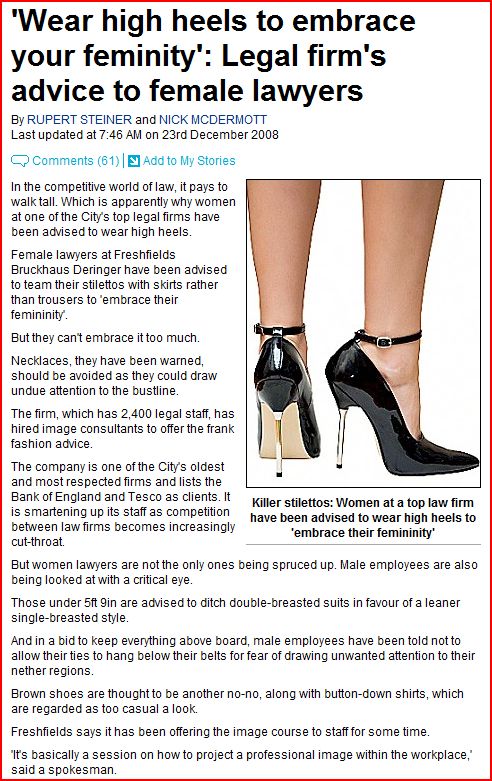

A Daily Mail story reports that women lawyers are being told by “image consultants’ that to appear “professional” they should enhance their femininity by wearing skirts and stilettos, but avoid drawing attention to their breasts. Thoughts about the word “professional” after the screenshot (thanks to Jason S. for the link):

A spokesman for the company doling out this advice says that it’s about being “professional.” This is a great term to take apart. What do we really mean when we say “professional”?

How much of it has to do with proper gender display or even, in masculinized workplaces, simply masculine display?

How much of it has to do with whiteness? Are afros and corn rows unprofessional? Is speaking Spanish? Why or why not?

How much of it has to do with appearing attractive, heterosexual, monogamous, and, you know, not one of those “unAmerican” religions?

For that matter, how much of it has to do with pretending like your work is your life, you are devoted to the employer, and your co-workers are like family (anyone play Secret Santa at work this year)?

What do we really mean when we say “professional”? How does this word get used to coerce people into upholding normative expectations that center certain kinds of people and marginalize others?

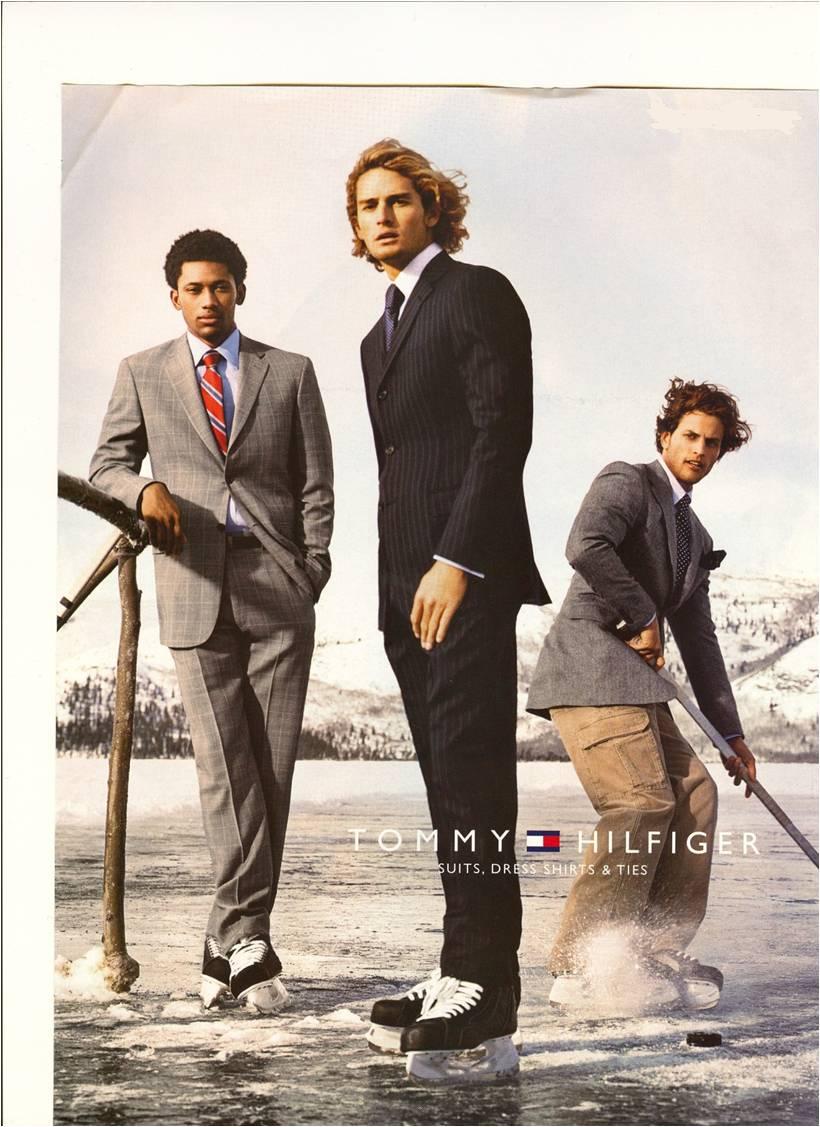

In this series I have offered five explanations of why people of color are included in advertising. Start with the first in the series and follow the links to the remaining four here.

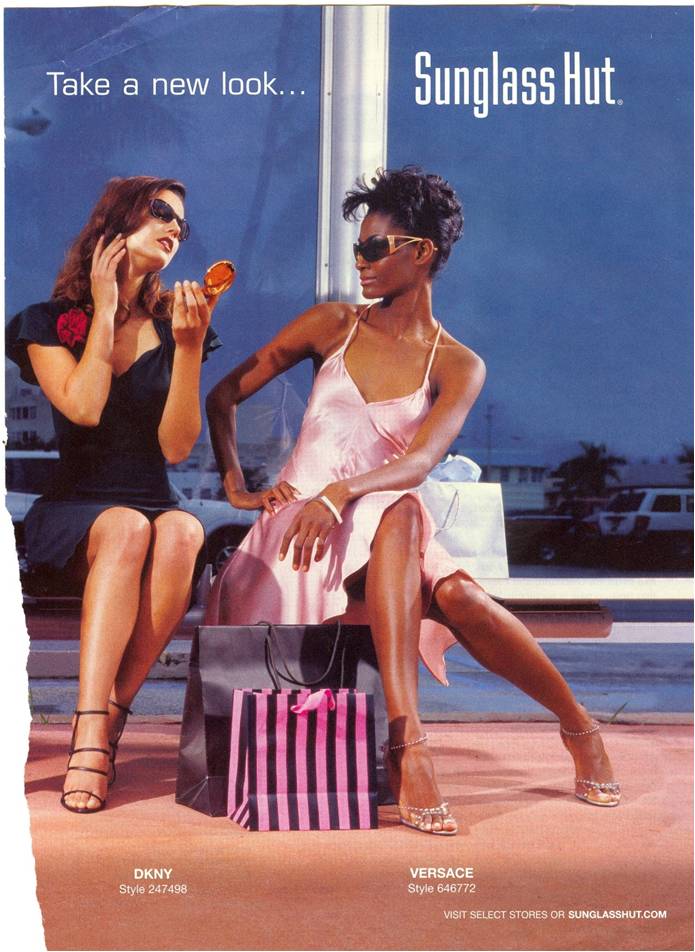

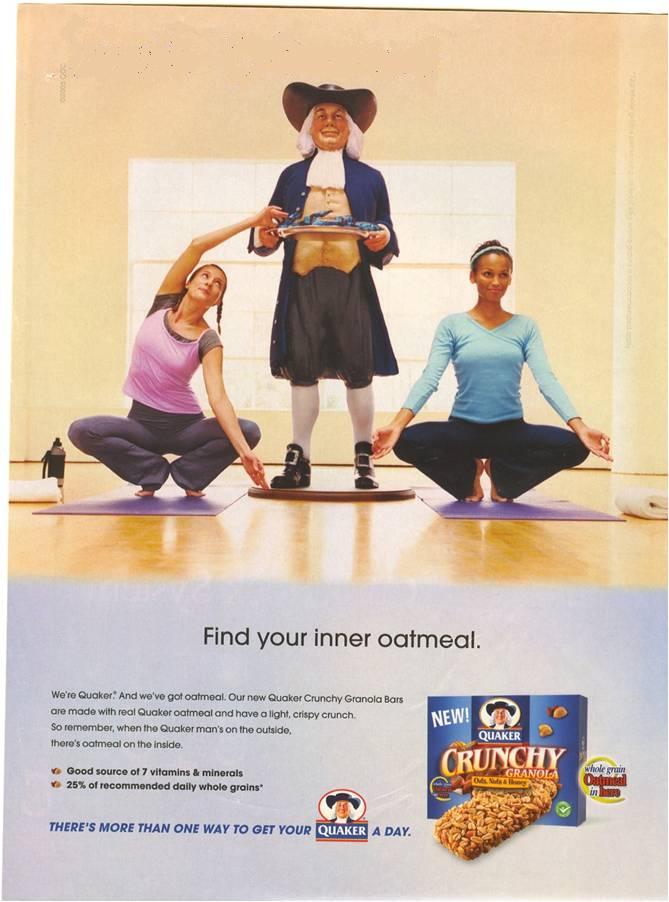

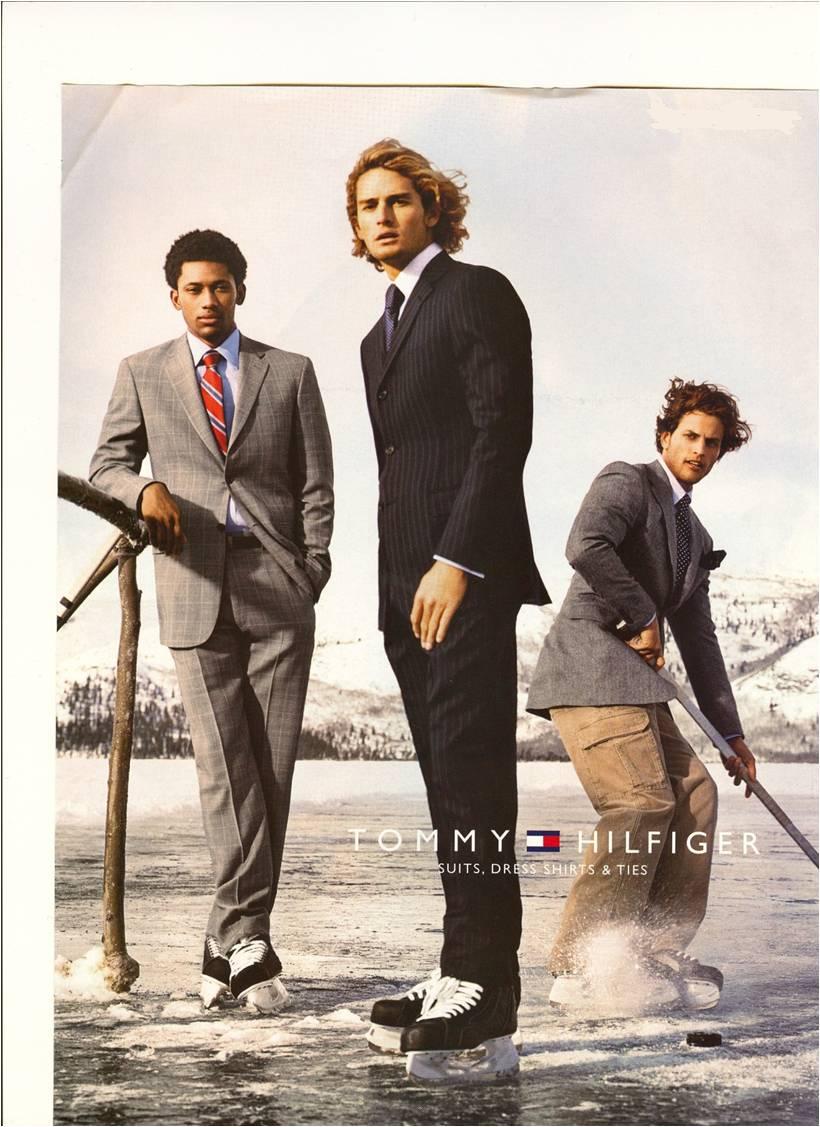

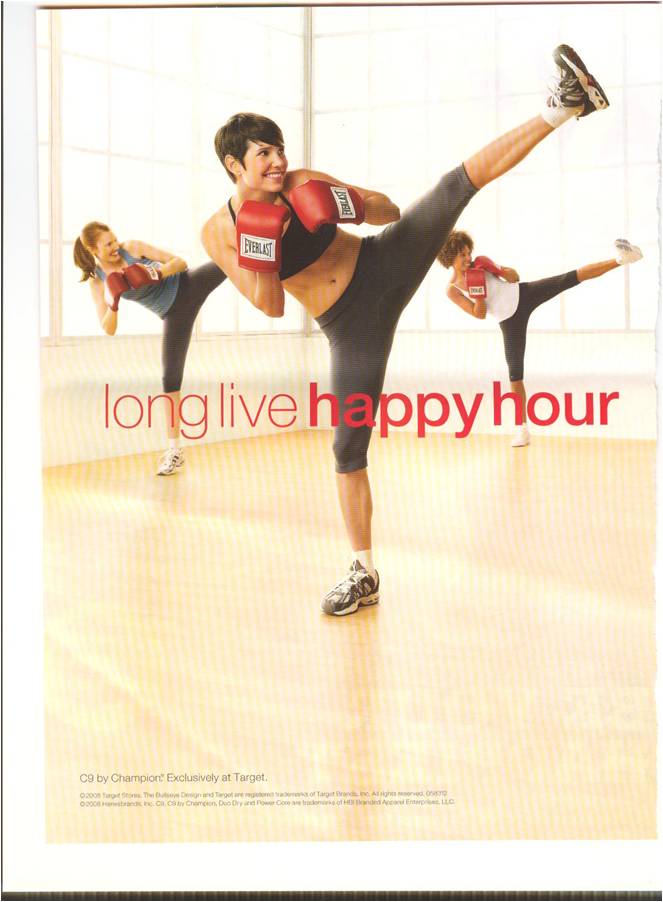

I am now discussing how they are included. Already I have shown that people of color are often whitewashed and that they tend to be chaperoned. Here I show that, when people of color are included, they are often subordinated through placement and action. That is, they tend to be literally background or arranged so that the focal point (visually or through action) is the white person or people in the ad. You’ll see a lot of this in the previous posts in this series if you go back and look again.

Darin F. sent in this example from a poster for McDonalds Happy Meals. He noted the way in which the women were arranged, closest to furthest, by skin color:

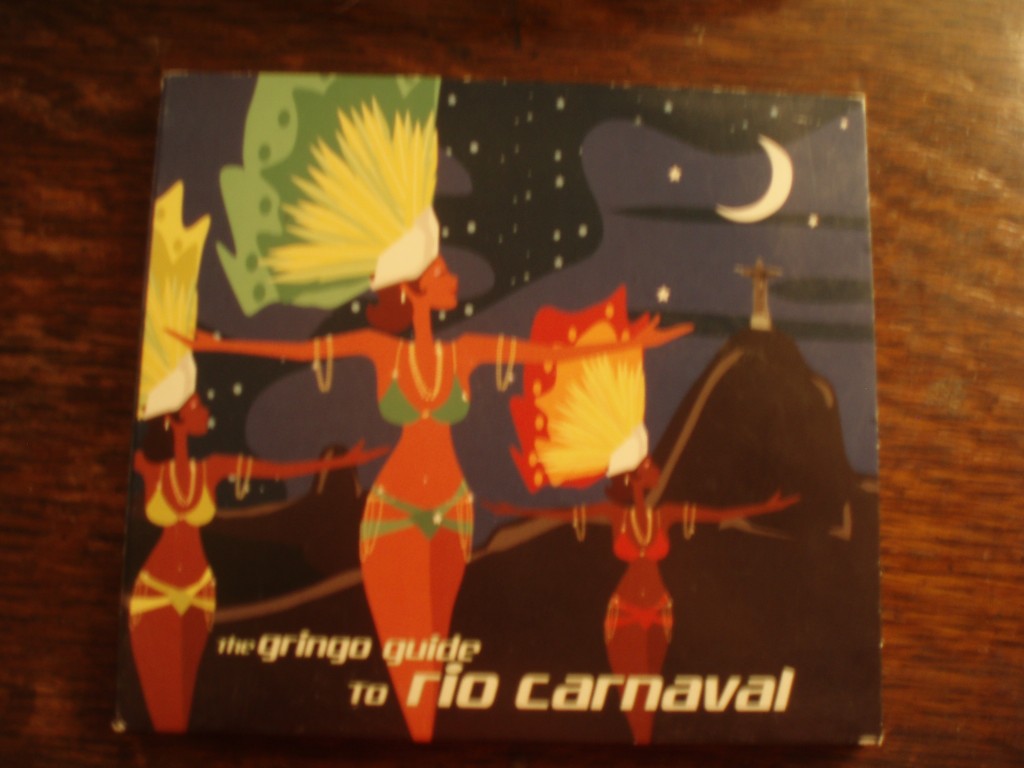

NEW! I found another example of this skin color hierarchy, this time on a CD cover:

More instances in which people of color are background:

In the next two ads, the center of attention–or the action–is where the white woman is:

Notice how in this ad, while there are three women of color (an exception to the tendency for people of color to be chaperoned), the woman front-and-center is clearly white:

Something similar is going on in these next two ads:

As Jean Kilbourne points out in her docmentary, Killing Us Softly, this visual representation of racial hierarchy tends to be found unless another axis of hierarchy is at work:

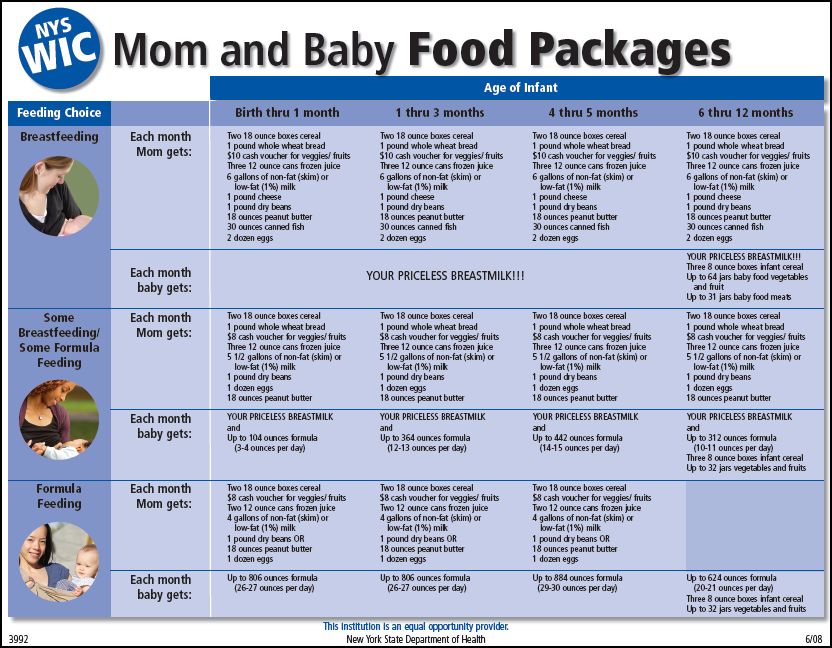

NEW (Mar. ’10)! Anina H. sent in this New York State flier advising mothers on feeding their babies. Notice that the flier includes women of three different races, but the ideal mother (“YOUR PRICELESS BREASTMILK!!!”) is white:

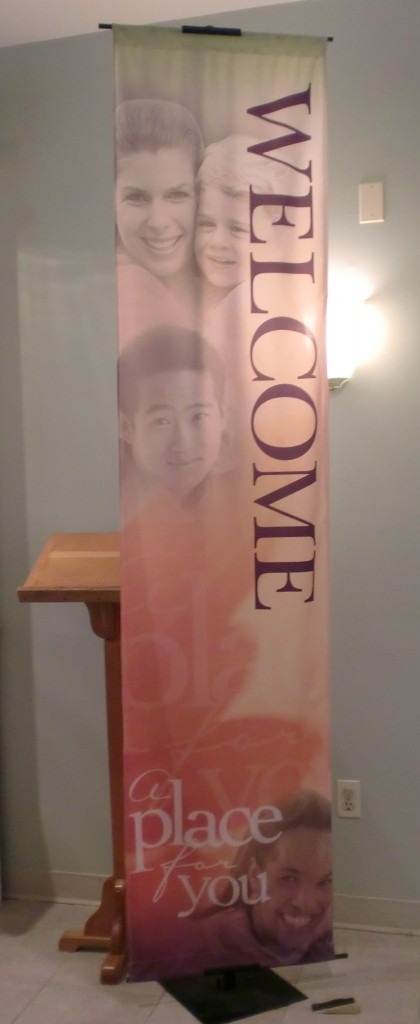

NEW (July ’10)! Naomi D. saw this welcome banner at the entrance of a Methodist Church. Notice how the racial hierarchy is represented on the banner with a White woman and child on the top, an Asian man below her, and a Black woman at the bottom of the banner:

As always, I welcome your comments!

Next up: Interracial dating, the last taboo.

Also in this series:

(1) Including people of color so as to associate the product with the racial stereotype.

(2) Including people of color to invoke (literally) the idea of “color” or “flavor.”

(3) To suggest ideas like “hipness,” “modernity,” and “progress.”

(4) To trigger the idea of human diversity.

(5) To suggest that the company cares about diversity.

How are they included?

(6) They are “white-washed.”

(7) They are “chaperoned.”

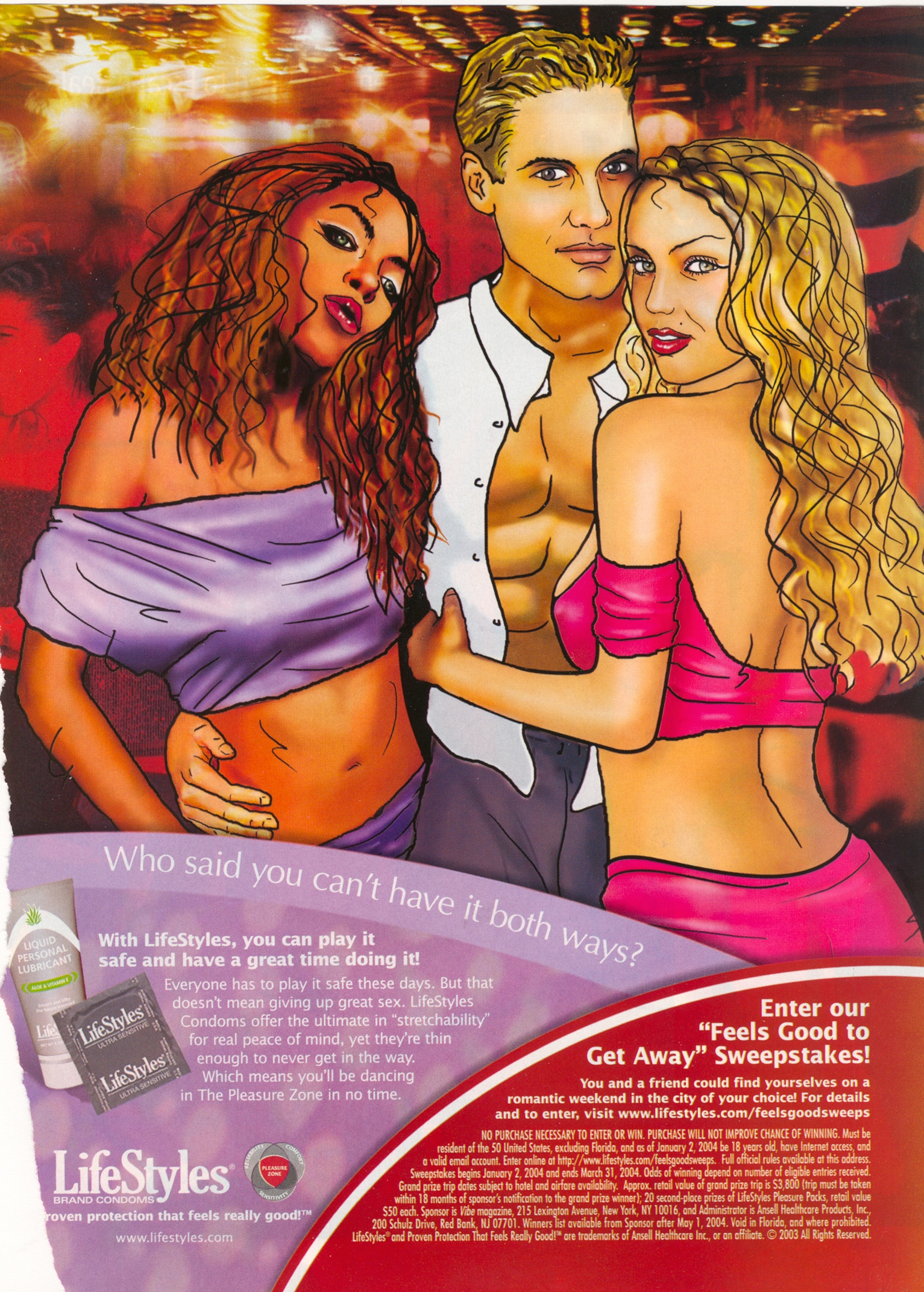

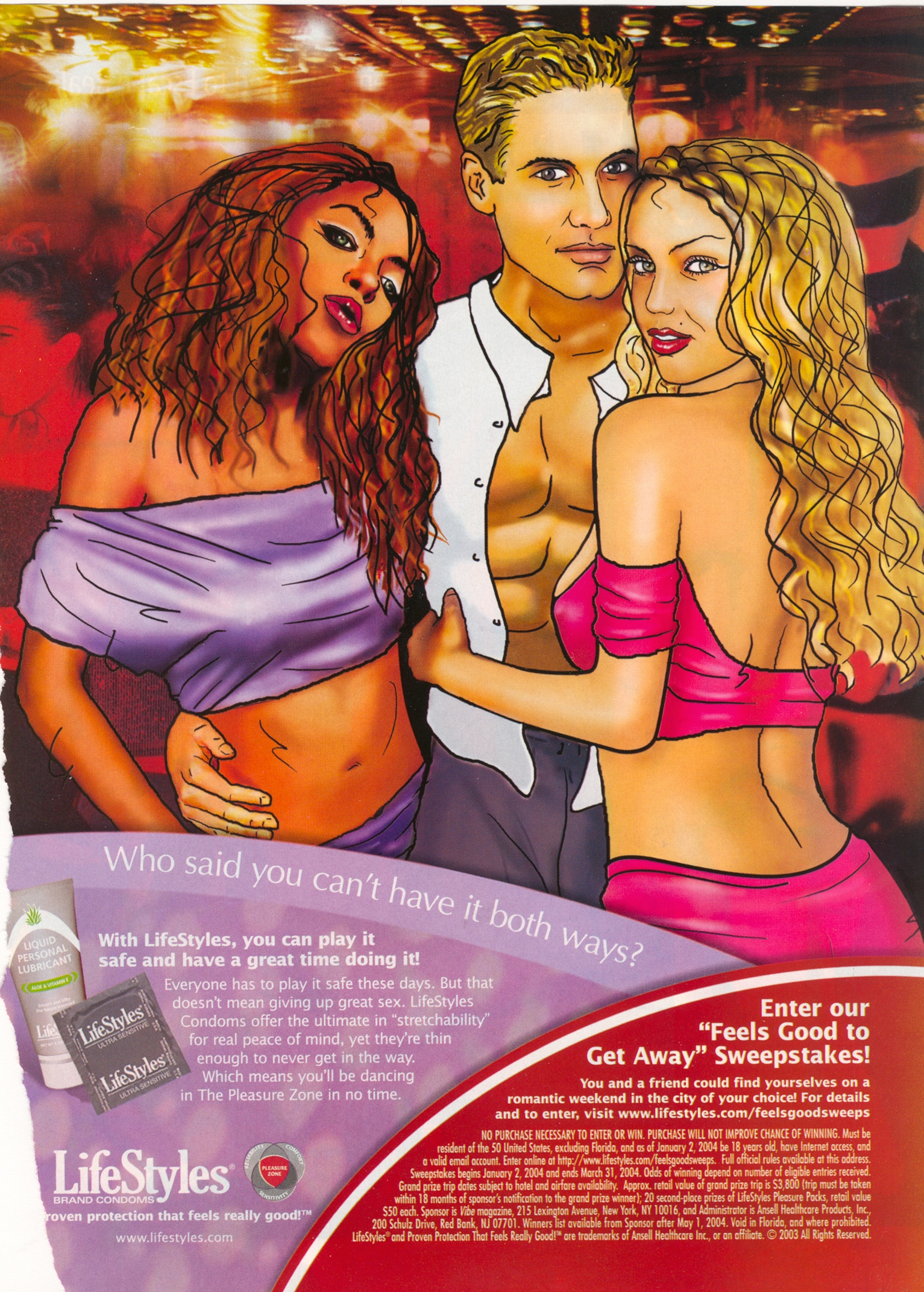

In this ad, the copy, which reads “Who said you can’t have it both ways,” refers explicitly to both “play[ing] it safe” with condoms and having “a great time” with “great sex.” Of course, implicitly, it also means not choosing between black and white women. Women are, in the subtext, objects to “have” and black and white women are very different kinds of objects.

A Cracked article compiled their candidates for the Nine Most Racist Disney Characters. Select stolen clips and liberal quoting below:

American Indians in Peter Pan:

Why do Native Americans ask you “how?” According to the song, it’s because the Native American always thirsts for knowledge. OK, that’s not so bad, we guess. What gives the Native Americans their distinctive coloring? The song says a long time ago, a Native American blushed red when he kissed a girl, and, as science dictates, it’s been part of their race’s genetic make up since. You see, there had to be some kind of event to change their skin from the normal, human color of “white.”

The bad guys in Alladin:

“Where they cut off your ear if they don’t like your face” is the offending line, which was changed on the DVD to the much less provocative “Where it’s flat and immense and the heat is intense.”

In a city full of Arabic men and women, where the hell does a midwestern-accented, white piece of cornbread like Aladdin come from? Here he is next to the more, um, ethnic looking villain, Jafar.

NEW: Miguel (of El Forastero) sent in a post from El Blog Ausente that compares an image of Goofy, a character generally portrayed as sort of dumb and lazy, to a traditional Sambo-type image:

The post suggests that Goofy is a racial archetype, built on stereotypical African American caricatures. I can’t remember ever seeing anything that suggested this, but that doesn’t mean much, and I certainly don’t put it past Disney to do so. Does anyone know of any other examples of Goofy supposedly being based on African American stereotypes? On the other hand, is it possible to depict a character eating watermelon in an exuberant manner without drawing on those racist images? When I look at the image of Goofy above, I have to say…that’s pretty much what it looks like when my (mostly White) family cuts a watermelon open out on the picnic table in the summer and everybody gets a piece and they all have ridiculous looks on their faces as they dribble juice all down themselves eating big chunks (I say “they” because I’m a weirdo who doesn’t really care for watermelon, so I rarely eat any, and even then only if I can put salt on it). I’m fairly certain that I couldn’t put up a photo of my family eating watermelon like that without it seeming, to many people, to draw on the Sambo-type imagery. It brings up some interesting thoughts about cultural and historical contexts, and how and in what circumstances you can (or can’t) escape them, regardless of your intent.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Laura Agustin, author of Sex at the Margins: Migration, Labour Markets, and the Rescue Industry, asks us to be critical consumers of stories about sex trafficking, the moving of girls and women across national borders in order to force them into prostitution. Without denying that sex trafficking occurs or suggesting that it is unproblematic, Agustin wants us to avoid completely erasing the possibility of women’s autonomy and self-determination.

About one news story on sex trafficking, she writes:

…[the] ‘undercover investigation’, one with live images, fails to prove its point about sex trafficking… reporters filmed men and women in a field, sometimes running, sometimes walking, sometimes talking together.

…I’m willing to believe that we’re looking at prostitution, maybe in an informal outdoor brothel. But what we’re shown cannot be called sex trafficking unless we hear from the women themselves whether they opted into this situation on any level at all. They aren’t in chains and no guns are pointed at them, although they might be coerced, frightened, loaded with debt or wishing they were anywhere else. But we don’t hear from them. I’m not blaming the reporters or police involved for not rushing up to ask them, but the fact is that their voices are absent.

…

There are lots of things we might find out about the fields near San Diego… [but] we don’t see evidence for the sex-trafficking story. Feeling titillated or disgusted ourselves does not prove anything about what we are looking at or about how the people actually involved felt.

Regarding a news clip, Agustin writes:

…a reporter dressed like a tourist strolls past women lined up on Singapore streets, commenting on their many nationalities and that ‘they seem to be doing it willingly’. But since he sees pimps everywhere he asks how we know whether they are victims of trafficking or not? His investigation consists of interviewing a single woman who… articulates clearly how her debt to travel turned out to be too big to pay off without selling sex. Then an embassy official says numbers of trafficked victims have gone up, without explaining what he means by ‘trafficked’ or how the embassy keeps track…

So here again, there could be bad stories, but we are shown no evidence of them. The women themselves, with the exception of one, are left in the background and treated like objects.

To recap, what Agustin is urging us to do is to refrain from excluding the possibility of women’s agency by definition. Why might a woman choose a dangerous, stigmatized, and likely unpleasant job? Well, many women enter prostitution “voluntarily” because of social structural conditions (e.g., they need to feed their children and prostitution is the most economically-rewarding work they can get). Assuming all women are forced by mean people, however, makes the social structural forces invisible. We don’t need mean pimps to force women into prostitution, our own social institutions do a pretty good job of it.

And, of course, we must also acknowledge the possibility that some women choose prostitution because they like the work. You might say, “Okay, fine, there may be some high-end prostitutions who like the work, but who could possibly like having sex with random guys for $20 in dirty bushes?” Well, if we decide that the fact that their job is shitty means that they are “coerced” in some way, we need to also ask about those people that “choose” other potentially shitty jobs like migrant farmwork, being a cashier, filing, working behind the counter at an airline (seriously, that must suck), factory work, and being a maid or janitor. There are lots of shitty jobs in the U.S. and world economy. Agustin simply wants us to give women involved in prostitution the same subject status as women and men doing other work.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

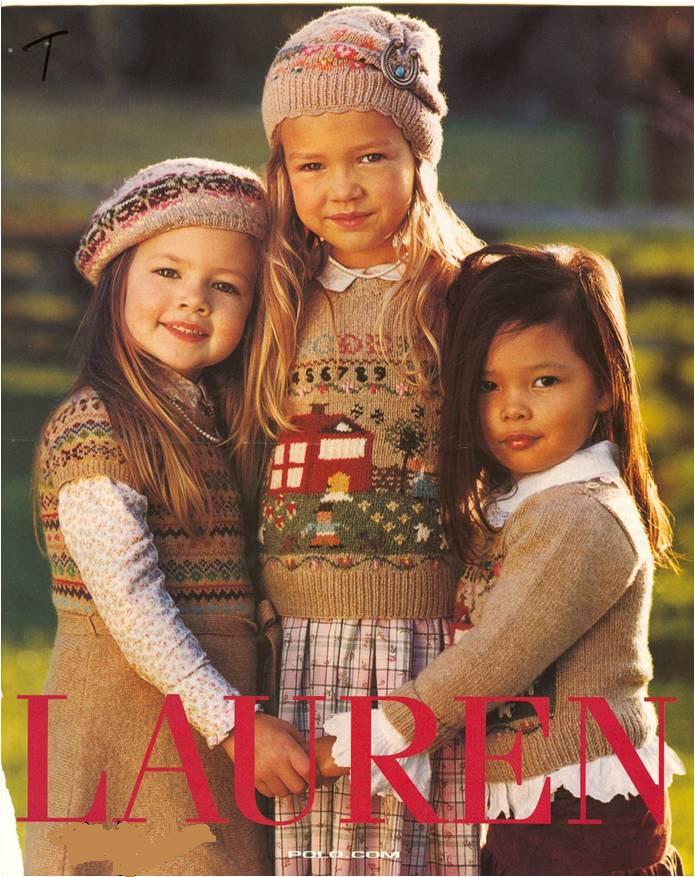

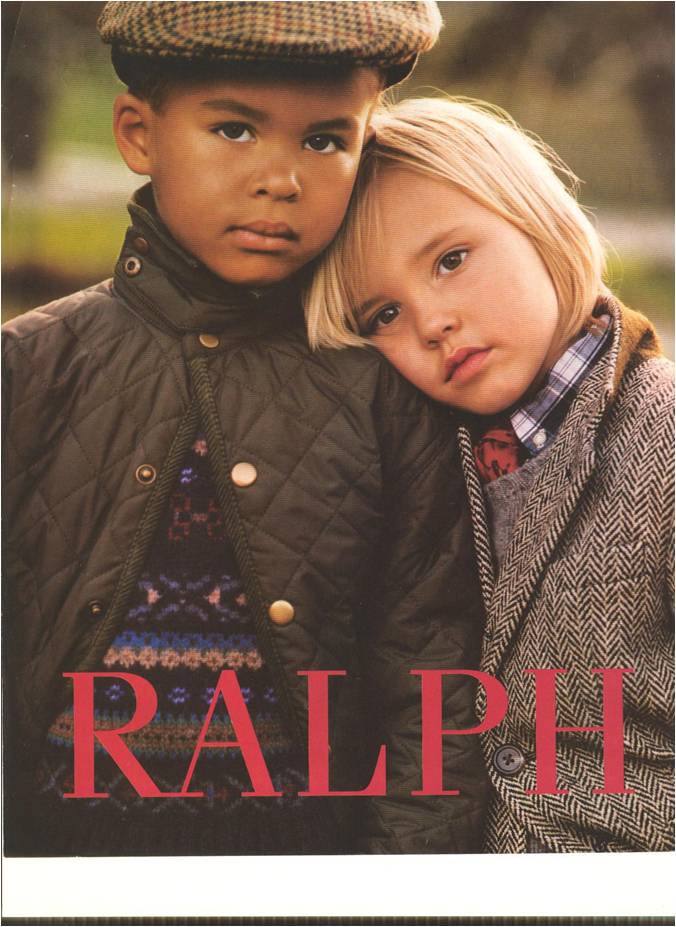

Maggie B. says:

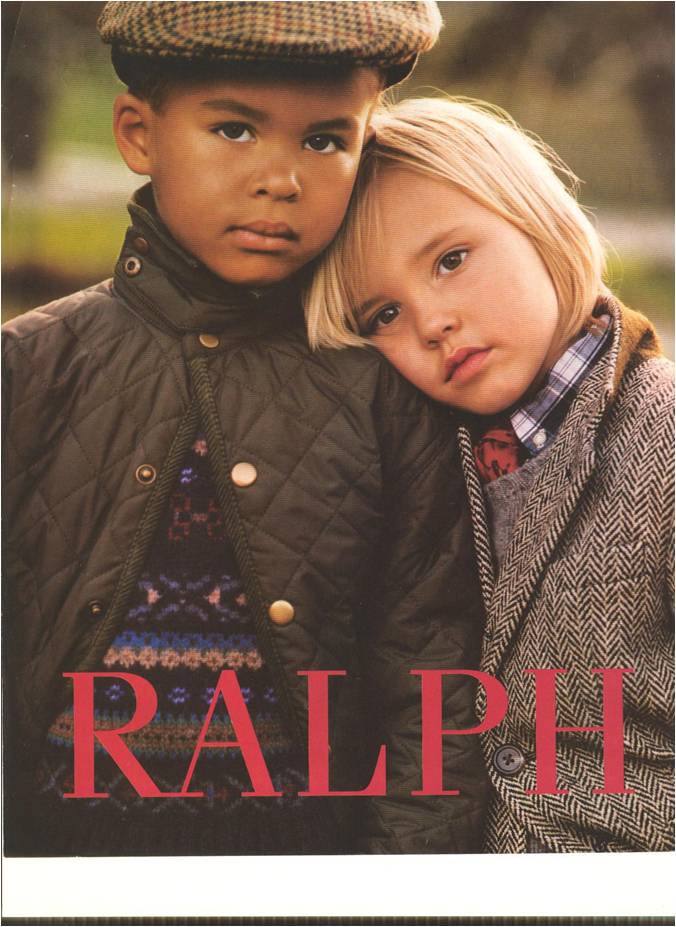

I was shocked and appalled when I saw these posters hanging above the children’s shoe section in a FootAction store in Jensen Beach, FL this weekend.

In her book, Bad Boys, Ann Ferguson argues that while white boys are seen as naturally and innocently naughty, black boys are seen as willfully bad. This is possible because teachers attribute adult motivations to black, but not white, children. Ferguson calls this adultification. Essentially this means that many teachers and other school authorities see black boys as “criminals” instead of kids. And black girls–also adultified, but differently–are seen as dangerously sexual. Adults, of course, are held 100% responsible for their behavior. There is no leeway here, no second chances, and no benefit of the doubt.

These pictures do more than just sexualize the young children pictured (who appear to be black and mixed-race), they also adultify them with their expressions, postures, fashion, and implied contexts.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

A Daily Mail story reports that women lawyers are being told by “image consultants’ that to appear “professional” they should enhance their femininity by wearing skirts and stilettos, but avoid drawing attention to their breasts. Thoughts about the word “professional” after the screenshot (thanks to Jason S. for the link):

A spokesman for the company doling out this advice says that it’s about being “professional.” This is a great term to take apart. What do we really mean when we say “professional”?

How much of it has to do with proper gender display or even, in masculinized workplaces, simply masculine display?

How much of it has to do with whiteness? Are afros and corn rows unprofessional? Is speaking Spanish? Why or why not?

How much of it has to do with appearing attractive, heterosexual, monogamous, and, you know, not one of those “unAmerican” religions?

For that matter, how much of it has to do with pretending like your work is your life, you are devoted to the employer, and your co-workers are like family (anyone play Secret Santa at work this year)?

What do we really mean when we say “professional”? How does this word get used to coerce people into upholding normative expectations that center certain kinds of people and marginalize others?

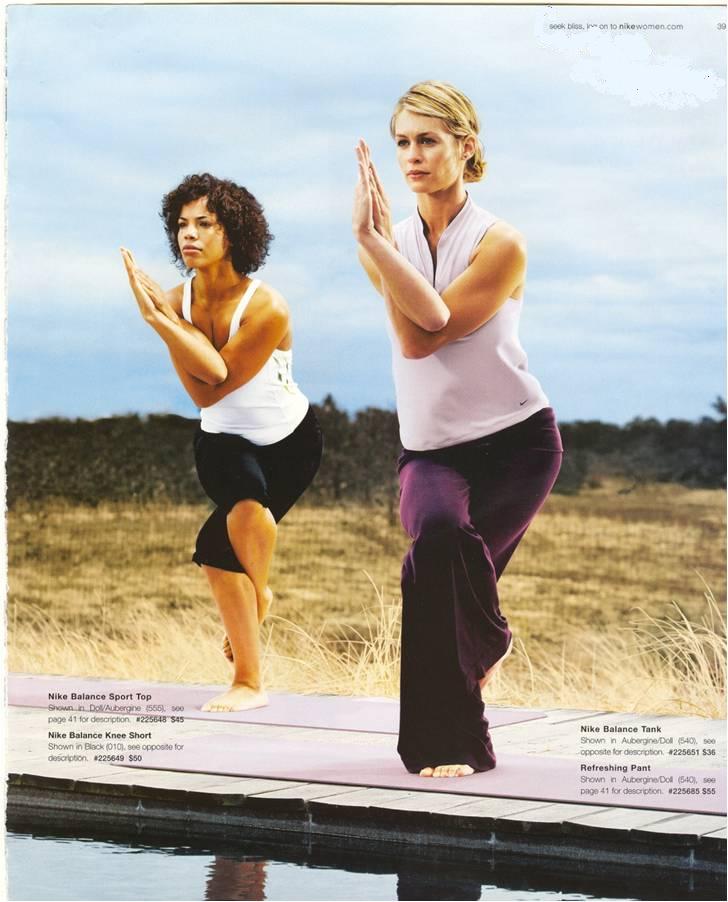

In this series I have offered five explanations of why people of color are included in advertising. Start with the first in the series and follow the links to the remaining four here.

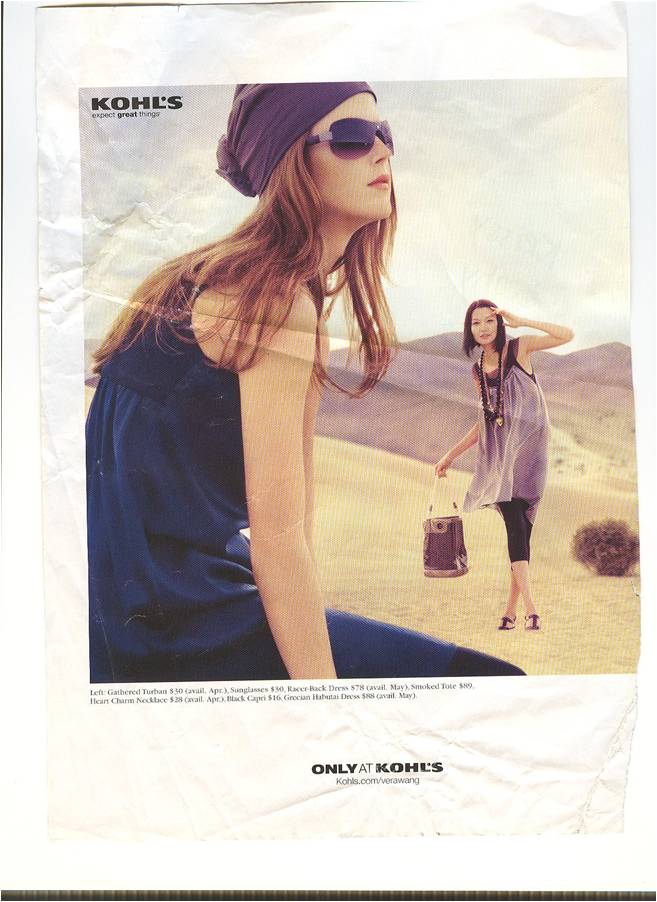

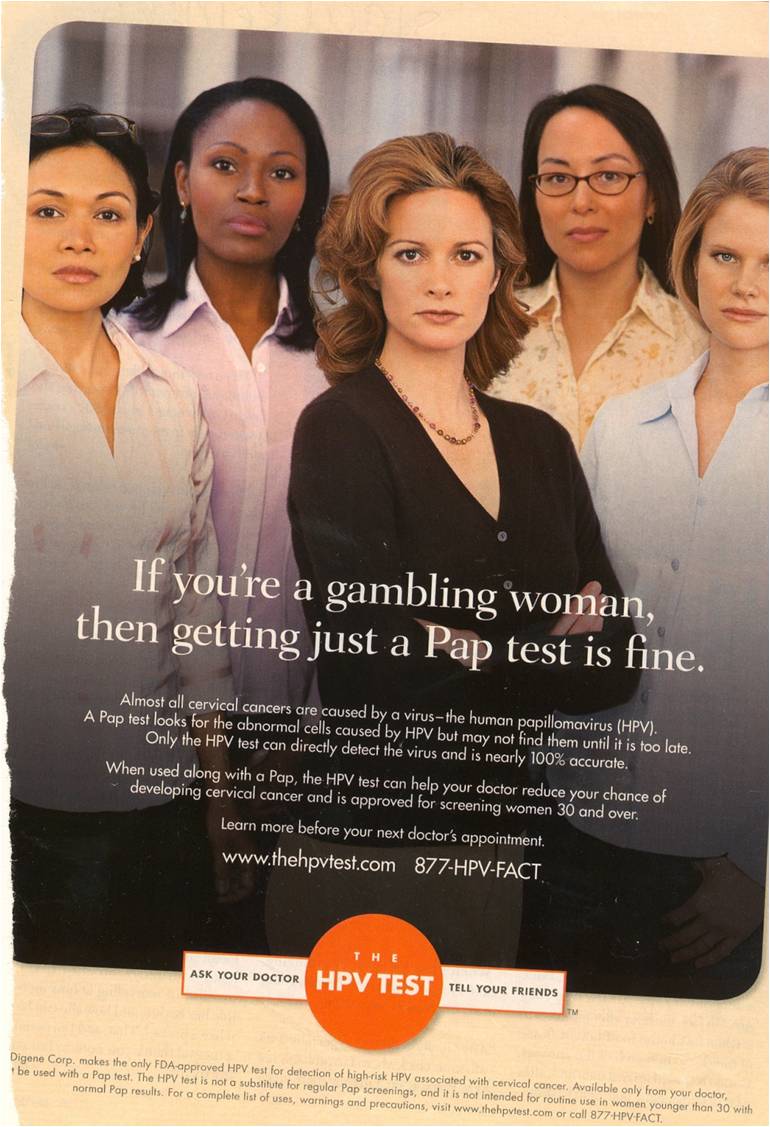

I am now discussing how they are included. Already I have shown that people of color are often whitewashed and that they tend to be chaperoned. Here I show that, when people of color are included, they are often subordinated through placement and action. That is, they tend to be literally background or arranged so that the focal point (visually or through action) is the white person or people in the ad. You’ll see a lot of this in the previous posts in this series if you go back and look again.

Darin F. sent in this example from a poster for McDonalds Happy Meals. He noted the way in which the women were arranged, closest to furthest, by skin color:

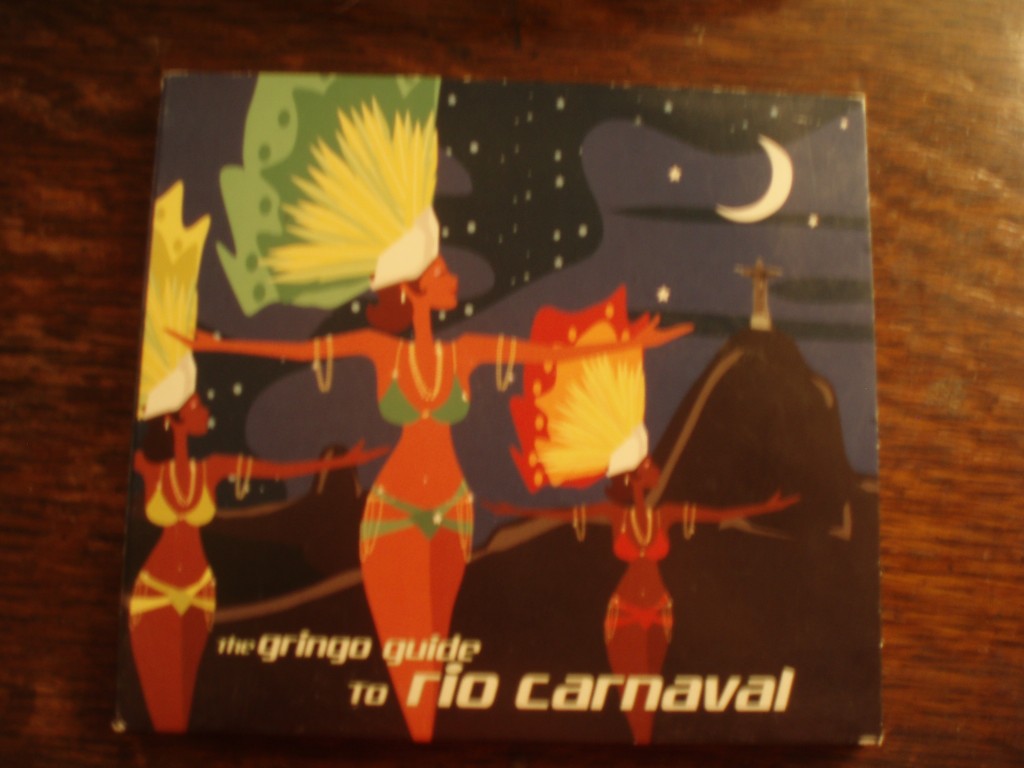

NEW! I found another example of this skin color hierarchy, this time on a CD cover:

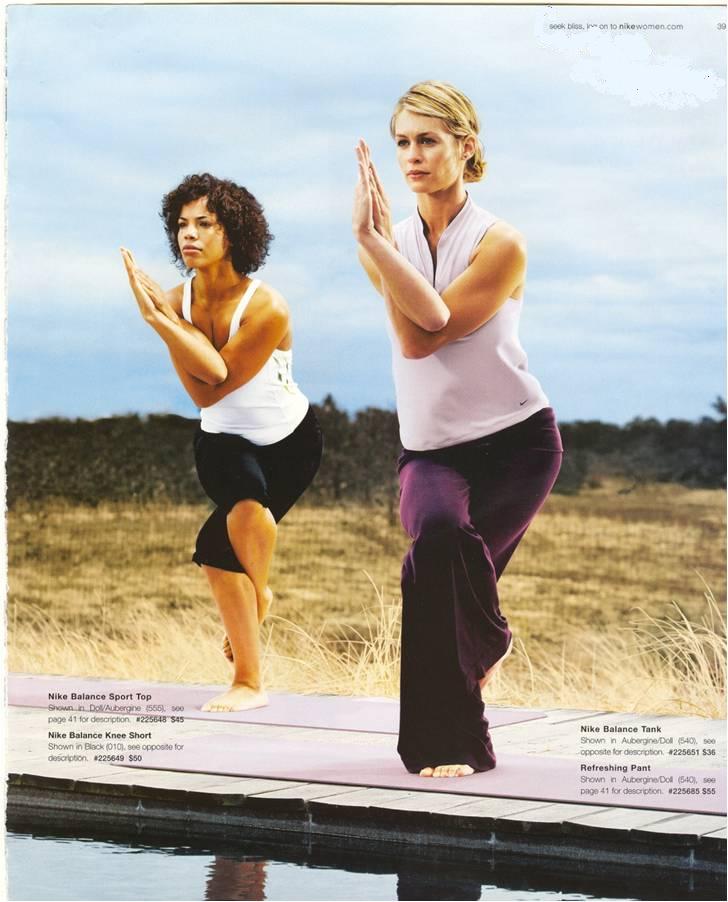

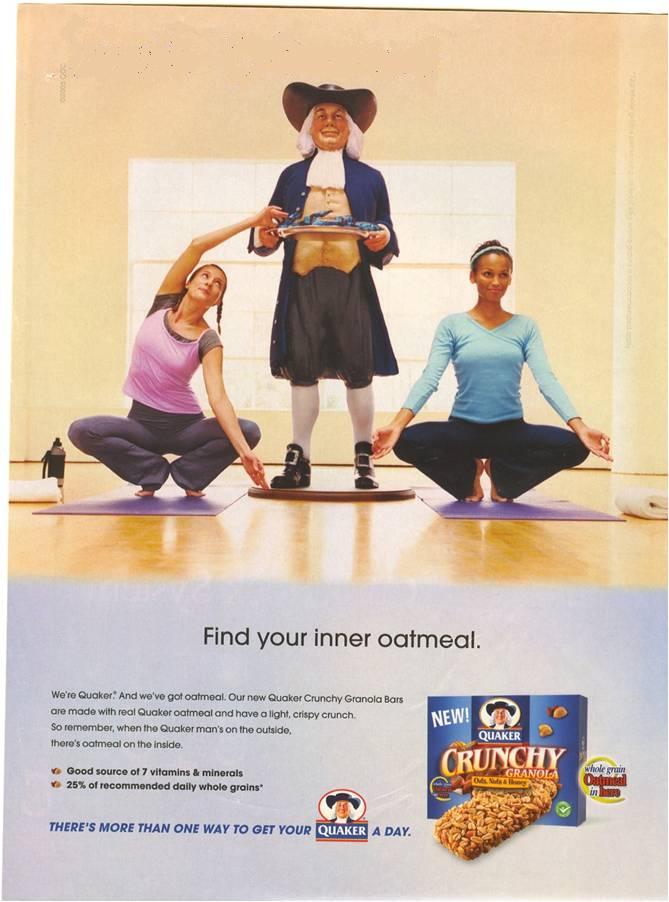

More instances in which people of color are background:

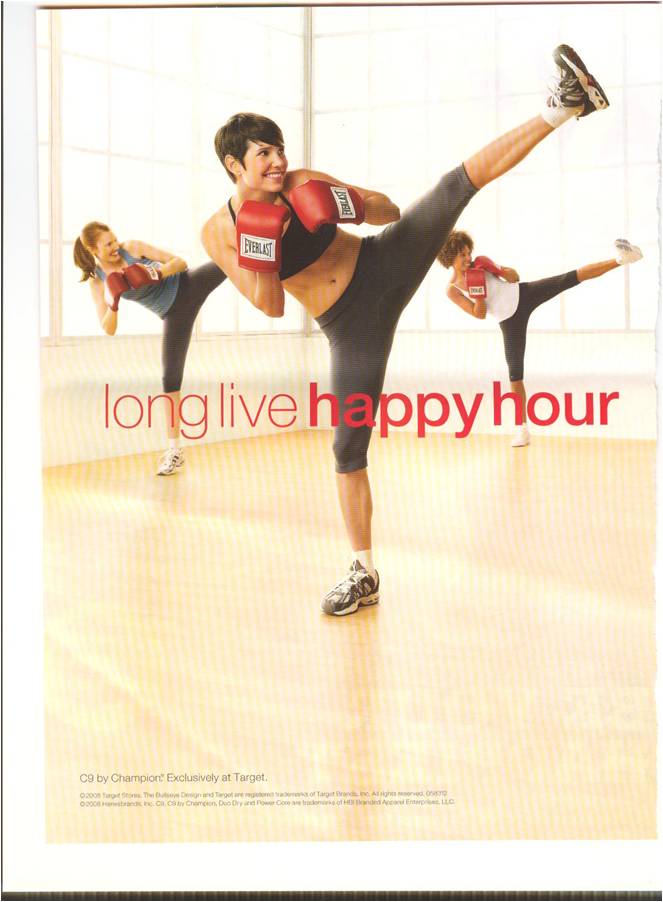

In the next two ads, the center of attention–or the action–is where the white woman is:

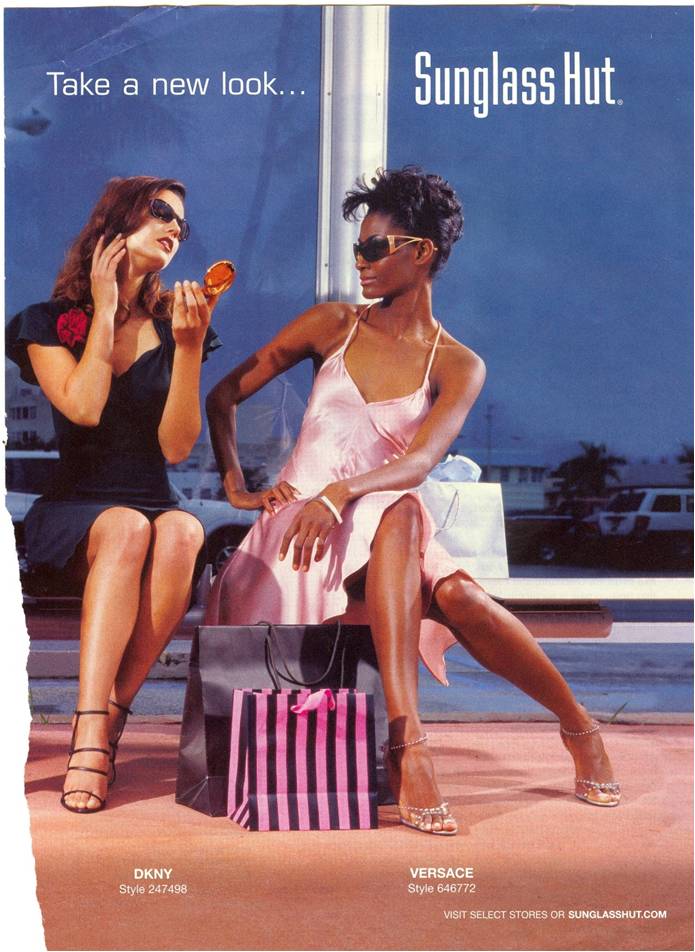

Notice how in this ad, while there are three women of color (an exception to the tendency for people of color to be chaperoned), the woman front-and-center is clearly white:

Something similar is going on in these next two ads:

As Jean Kilbourne points out in her docmentary, Killing Us Softly, this visual representation of racial hierarchy tends to be found unless another axis of hierarchy is at work:

NEW (Mar. ’10)! Anina H. sent in this New York State flier advising mothers on feeding their babies. Notice that the flier includes women of three different races, but the ideal mother (“YOUR PRICELESS BREASTMILK!!!”) is white:

NEW (July ’10)! Naomi D. saw this welcome banner at the entrance of a Methodist Church. Notice how the racial hierarchy is represented on the banner with a White woman and child on the top, an Asian man below her, and a Black woman at the bottom of the banner:

As always, I welcome your comments!

Next up: Interracial dating, the last taboo.

Also in this series:

(1) Including people of color so as to associate the product with the racial stereotype.

(2) Including people of color to invoke (literally) the idea of “color” or “flavor.”

(3) To suggest ideas like “hipness,” “modernity,” and “progress.”

(4) To trigger the idea of human diversity.

(5) To suggest that the company cares about diversity.

How are they included?

(6) They are “white-washed.”

(7) They are “chaperoned.”

In this ad, the copy, which reads “Who said you can’t have it both ways,” refers explicitly to both “play[ing] it safe” with condoms and having “a great time” with “great sex.” Of course, implicitly, it also means not choosing between black and white women. Women are, in the subtext, objects to “have” and black and white women are very different kinds of objects.