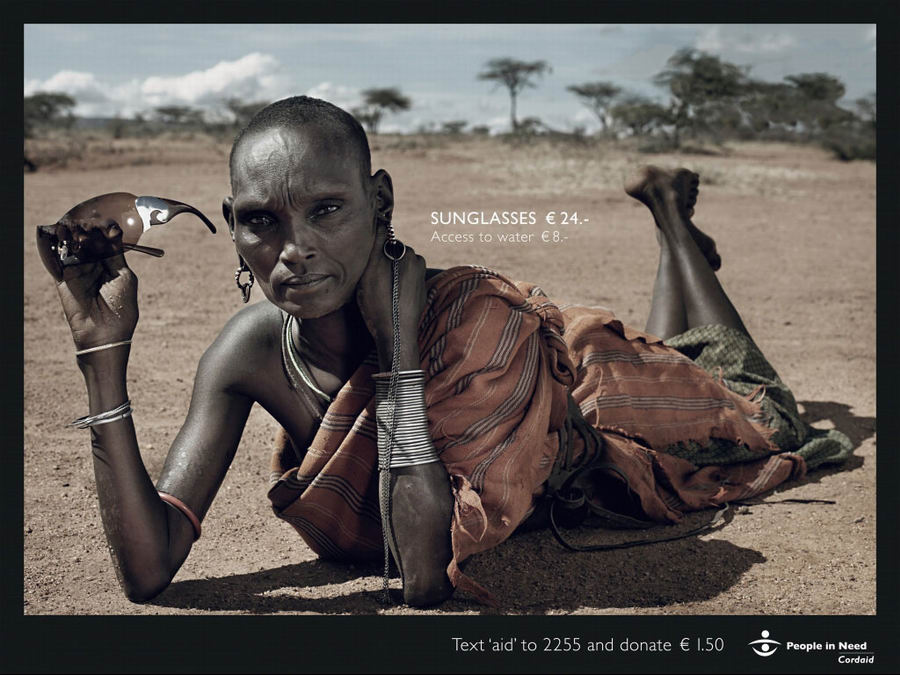

Ghanimah A. sent us these images for Cordaid, an “international development organisation” that specializes in “emergency aid and structural poverty eradication.” We would love to know what you think.

race/ethnicity: Blacks/Africans

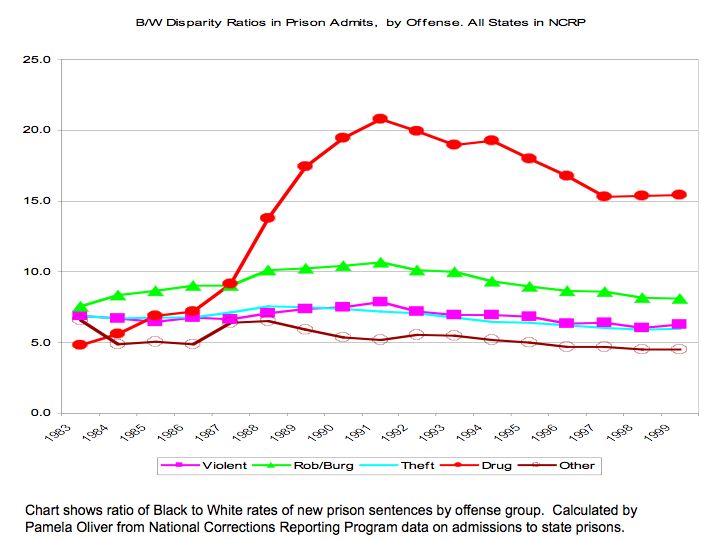

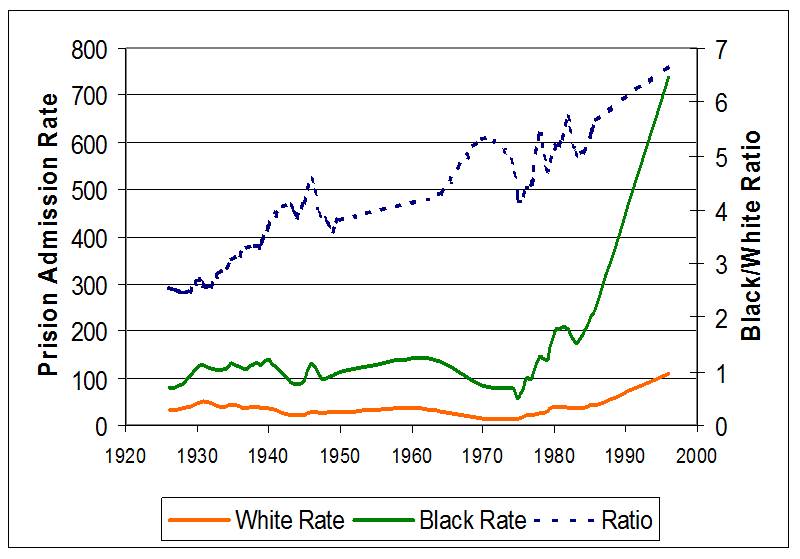

Pam Oliver sent in this graph that shows disparities in Blacks’ and Whites’ new prison sentences:

While blacks are more likely to be sentenced for all the offenses shown, clearly drug offenses stand out as the area with the biggest racial disparity in prison sentences. The other thing that stands out is the huge jump that occurred in the late 1980s and how much higher the disparity was by the 1990s than in the 1980s. Either African Americans suddenly started doing a whole lot more drugs, Whites stopped doing them altogether…or Blacks started getting arrested and sentenced at a much higher rate than Whites for drug offenses.

From an article by Oliver:

…the rise in imprisonment since the 1970s is not explained by crime rates, but by changes in policies related to crime…Determinate sentencing, which eliminates judicial discretion, longer sentences for drug offenses, increases in funding for police departments and large increases in prison capacity, the exacerbation of racial tensions and fears following the civil rights movement and the riots of the 1970s, and the politicization of crime as an election issue all seem to have played some role.

In Focus 21 (3) pp. 28-31 Spring 2001.

Other sociologists have pointed out that Whites tend to sell drugs inside buildings (houses, dorm rooms, workplaces) to people they know, while Blacks are more likely to engage in open-air sales to strangers. It’s much easier for police to see and arrest people engaged in open-air sales because they’re visible and, being out in public, can often be stopped and frisked without a warrant. Clearly it would be more difficult to know about drug sales taking place in private residences, and there would be more procedural hurdles to searching for them. And when you’re selling to strangers, you’re more likely to see to an undercover cop or to sell to people who don’t really have a problem saying who they bought their drugs from. So the very manner in which they sell makes it much more likely that Blacks will be caught and arrested, even though enormous amounts of drugs are bought and sold by Whites.

You can find a lot more graphs and articles on this topic (including disparities broken down by state) at Pam Oliver’s website. Also see this post about international imprisonment rates. Thanks, Pam!

Oh, and Lisa’s at the American Sociological Association meetings, which is why you’re stuck with just me this week.

Did you know that the U.S. has a higher imprisonment rate than even Russia? And the U.S. imprisonment rate is about six times that of many European countries.

(This first figure was made by Kieran Healy.)

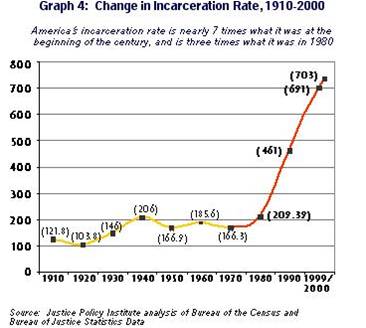

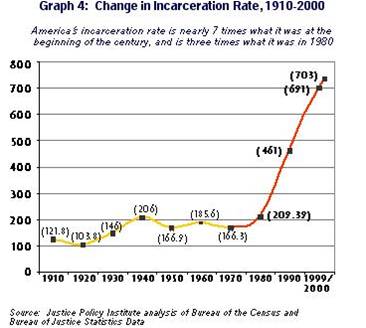

When and how did this happen? It started in the 1980s with Reagan’s “war on drugs.” The figure below shows the increase in the incarceration rate beginning in the 1980s (# of people out of 100,000).

So our imprisonment rate is the result of imprisoning people who break drug laws, NOT violent criminals or even people who commit property crimes. The increase is largely due to more aggressive policing of drug law violations.

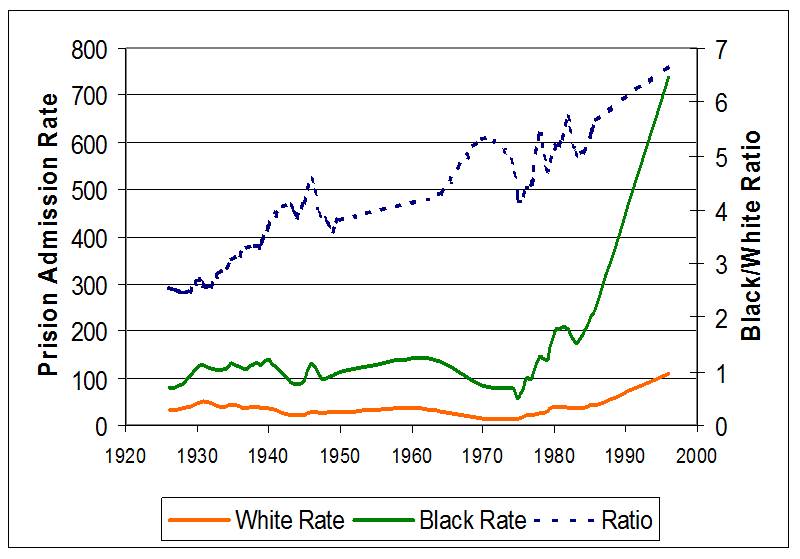

And, as you can see in the figure below, the aggressive policing of drug law violations can be found disproportionately in black neighborhoods. (White and black people take drugs at a very similar rate, but black neighborhoods are more heavily policing and drugs more common among blacks than white have carried heavier sentences — i.e., crack versus cocaine until recently). This figure shows that the increase in the incarceration rate is mostly an increase in the black incarceration rate.

Thanks to the amazing Pam Oliver for reminding me that this last graph comes from her work on the incarceration rate (found here).

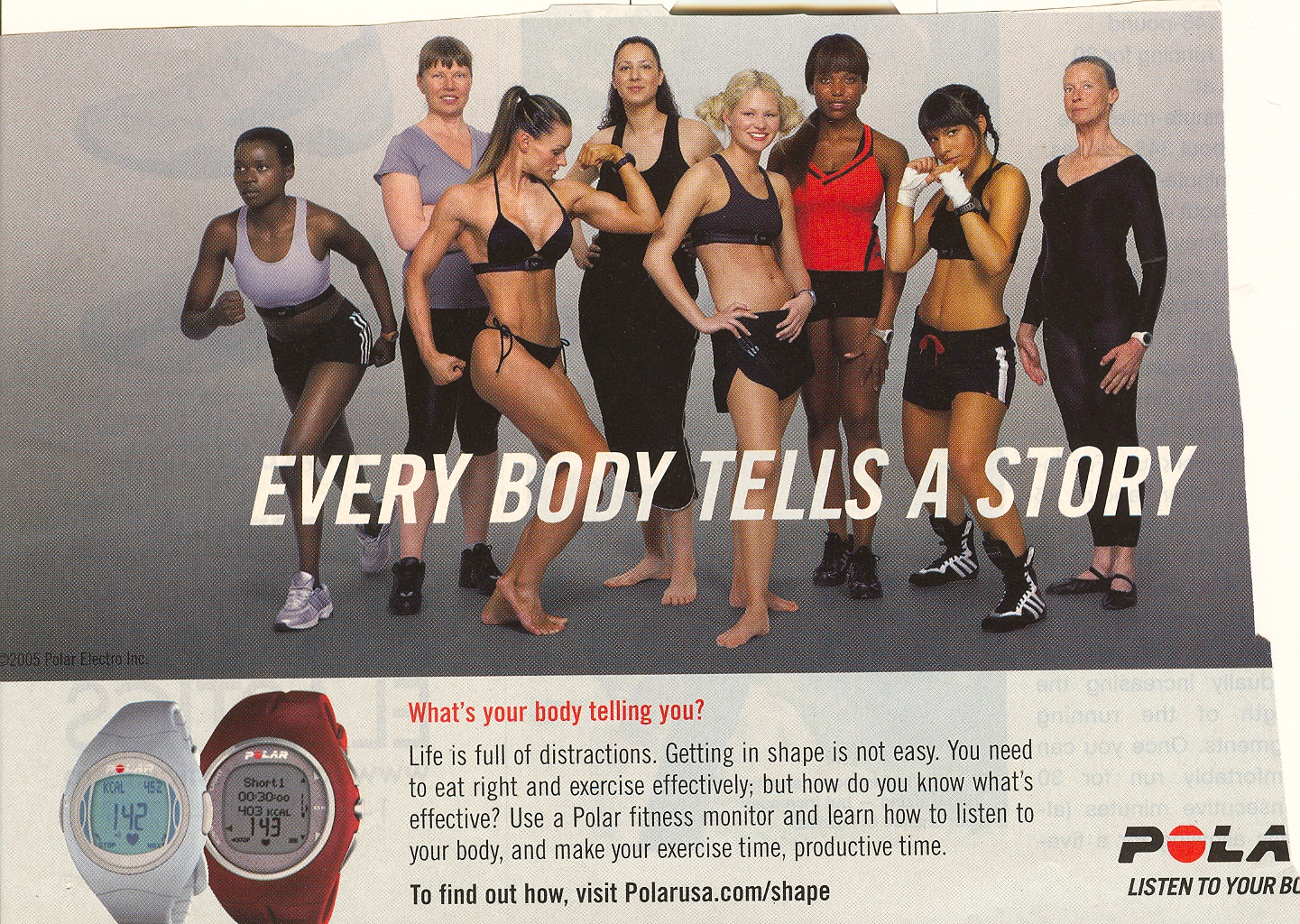

This is the fourth installment in a series on why and how people of color are included in advertising aimed primarily at white people. In the first installment, I argued that people of color are included in such advertising in order to associate the product with a racial stereotype (i.e., hipness, intelligence). In the second, I showed how people of color can be used to give a product “color” or “flavor.” And, in the third, I argued that people of color are used to invoke ideas of “hipness,” “modernity,” “progressive” politics and other related ideas. In this post, I suggest that people of color are used to trigger the idea of human variation itself.

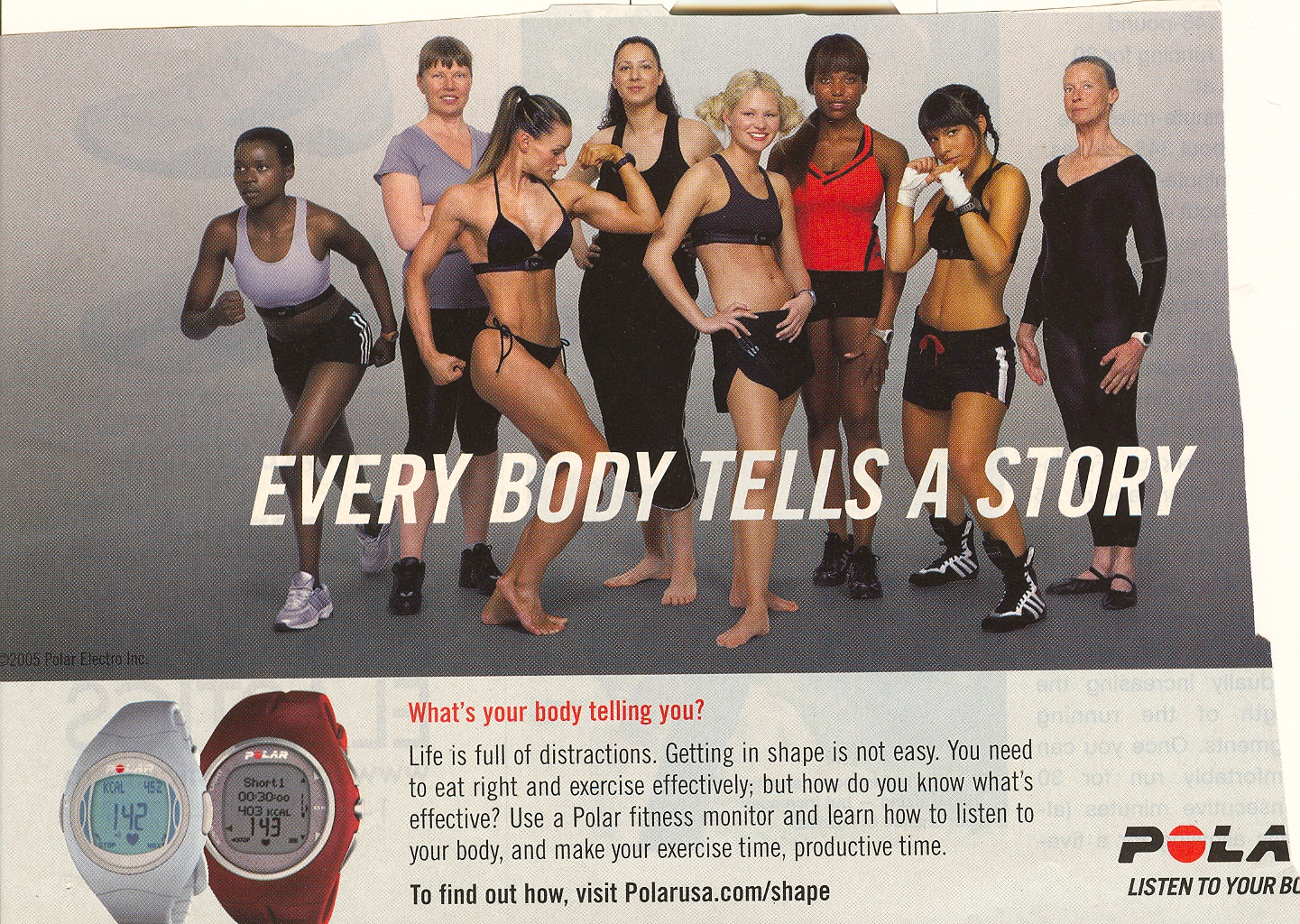

In this first ad the idea that each body is different is illustrated by including women of different fitness levels, ages, and races.

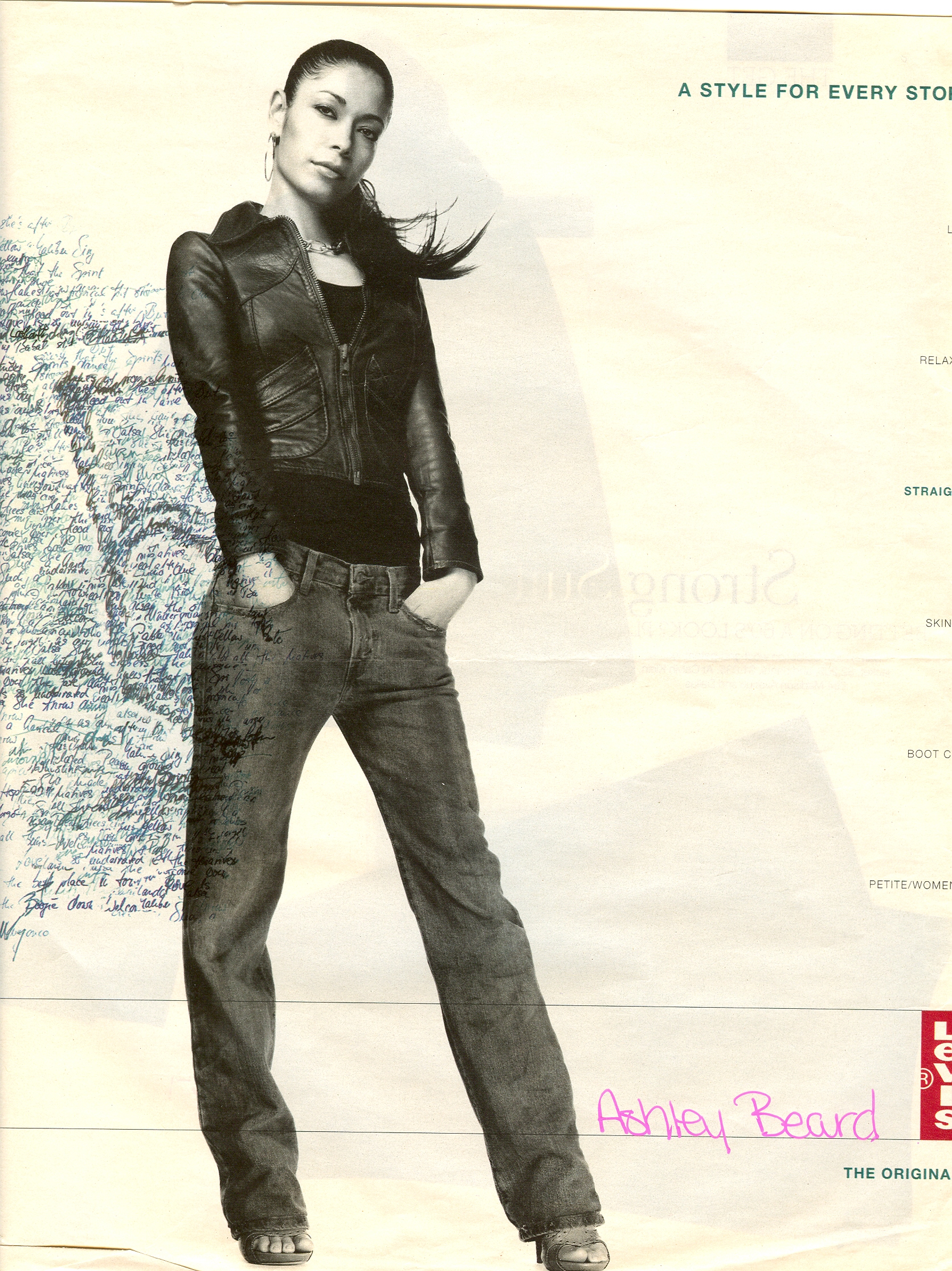

In this ad, Levi’s uses a woman who appears Latina to sell their jeans, which come in various fits because there is “a style for every story.” The idea is that people are different; not everyone wants the same cut of jeans.

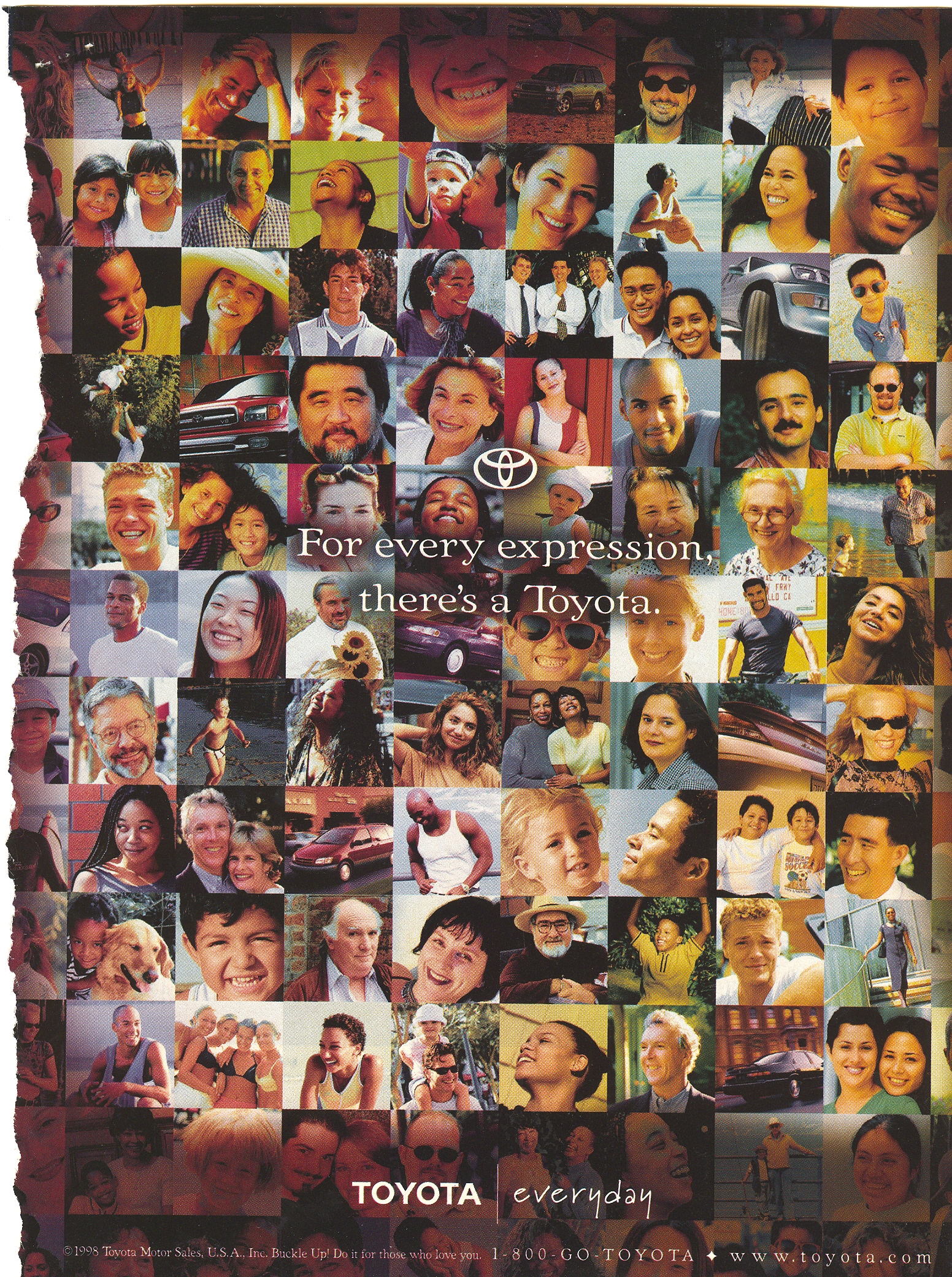

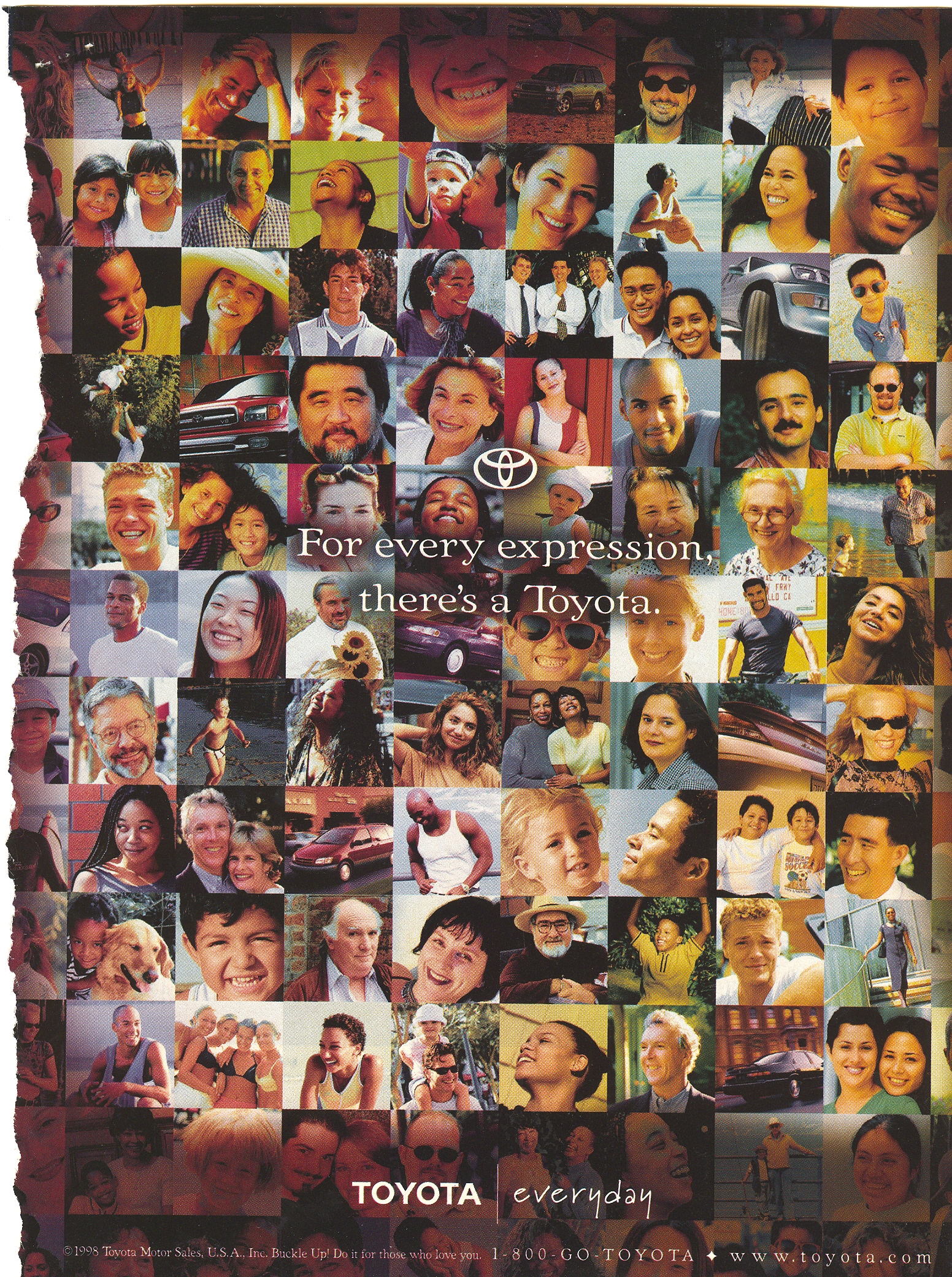

In this Toyota ad, the copy says “For every expression, there’s a Toyota.” People are unique and so, apparently, are Toyotas. Race is used to communicate the notion of human diversity.

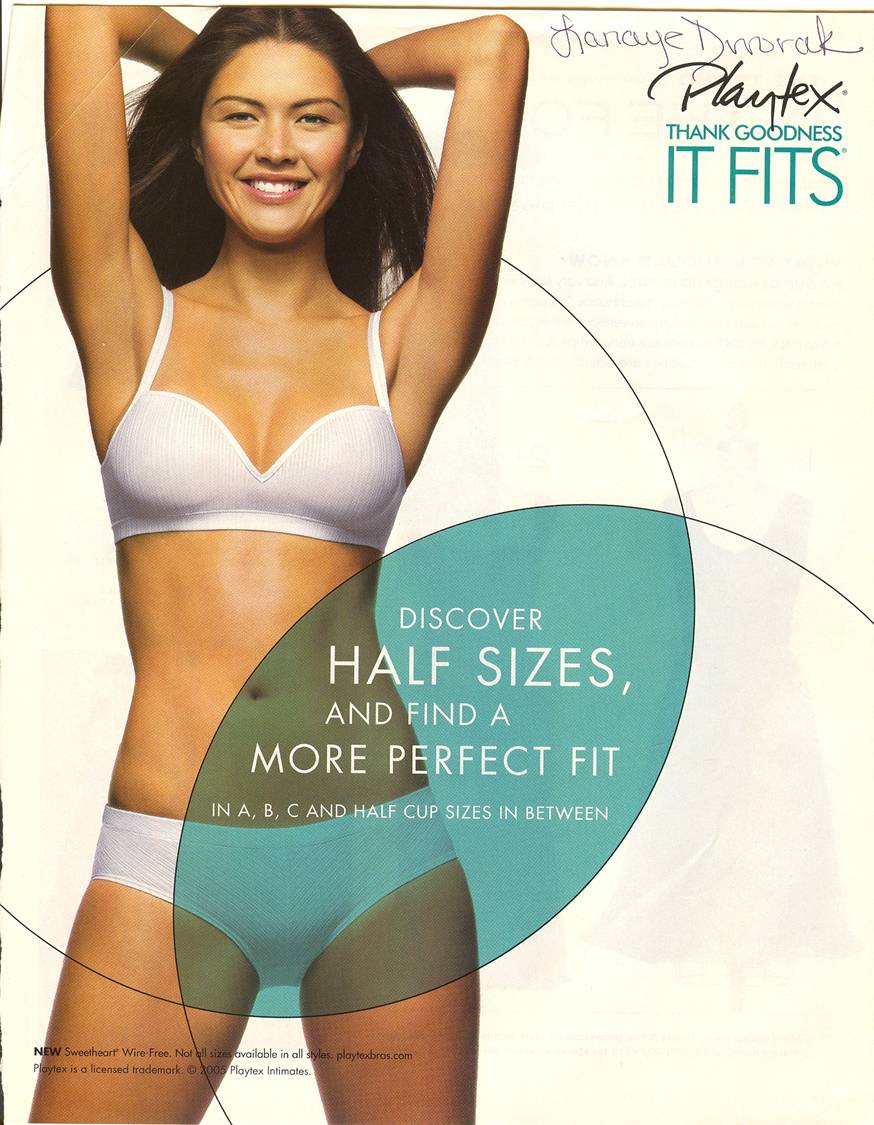

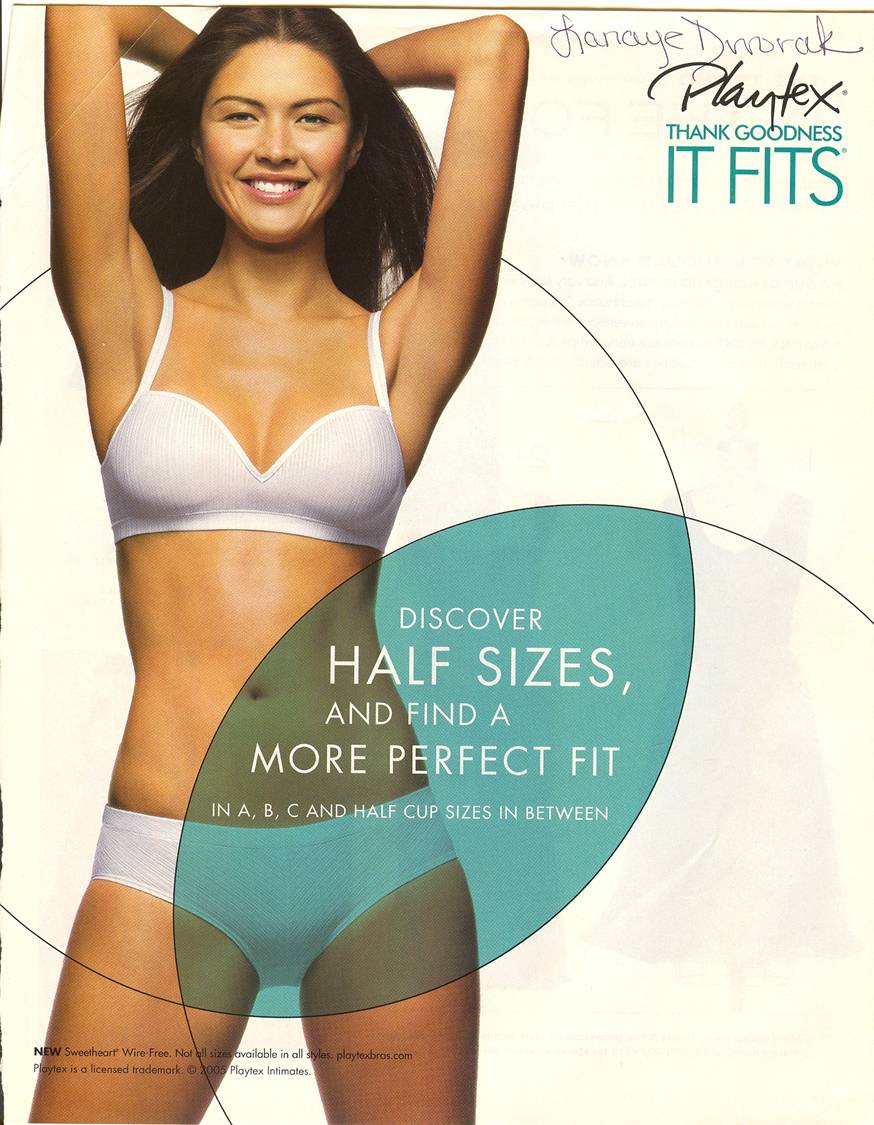

This is an ad for Playtex bras with half sizes. The implication is that people’s bodies are more variable than the A, B, C etc sizes suggest, so half sizes accomodate that variety. I think this ad is particularly interesting because the model is racially ambiguous. Maybe she’s half Asian, Latina, or white, and she’s being used to sell a product that now comes in half sizes.

NEW:

Next up: Including people of color so as to suggest that the company is concerned with racial equality.

See the other posts in the series:

(1) Including people of color so as to associate the product with the racial stereotype.

(2) Including people of color to invoke (literally) the idea of “color” or “flavor.”

(3) Triggering ideas like “hipness,” “modernity,” and “progress.”

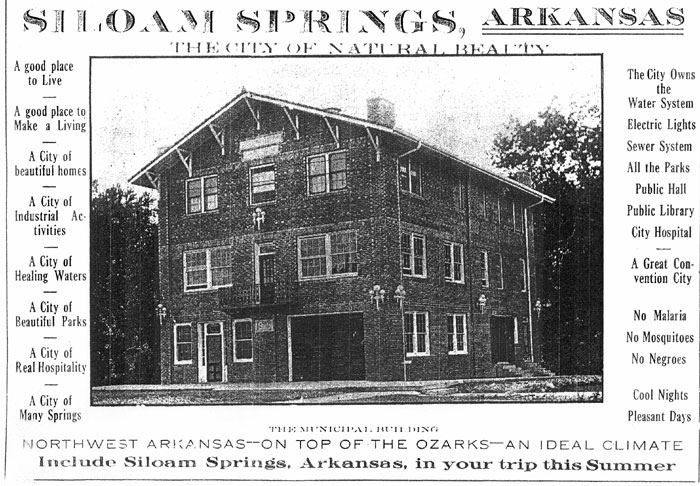

In his book Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism (2005; New York: Touchstone), James Loewen discusses cities that had a “no Blacks after dark” policy. They were called “sundown towns” because African Americans were actively informed that they should be out of town by sundown; if not, they were subject to arrest or violence. Of course, the purpose of these regulations was to keep Blacks from settling permanently in these towns. If they couldn’t be in town limits after dark, they clearly couldn’t live there. Here is an example of a sundown town: this ad encouraging people to move to Siloam Springs, Arkansas, says, over in the lower right corner, “No Malaria, No Mosquitoes, No Negroes.”

Found here.

NOTE: As Mr. Loewen pointed out in a comment, I had originally said he discussed “cities in the South,” as though that was all his book concentrated on. That was poor wording on my part, as I had been reading the sections of the book that covered some areas in the South I was specifically interested in (particularly Oklahoma). I did not mean to imply that sundown towns existed only in the South or that Mr. Loewen only discusses the South.

Ben O. sent in the video for “Take You There,” by Sean Kingston. Ben said, “The premise of Sean Kingston’s song ‘Take You There’ is that driving through slums is a great idea for a romantic date.”

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=axq1jQTk84w[/youtube]

My original thought, before I watched the video, was that maybe Kingston (who, according to Wikipedia, was born in Miami but mostly raised in Kingston, Jamaica) was trying to humanize the kinds of low-income neighborhoods that non-residents often believe are uniformly terrifying and that anyone who would venture there is going to their certain death. Or, if not that, maybe to show some of the horrid realities of living in economically devastated areas.

Then I watched the video. What struck me is how every resident is portrayed as glowering, threatening, and angry; they’re all the stereotype of the aggressive Angry Black Man.

The other thing that’s interesting is the gender elements. First, here are some of the lyrics:

We can go to the tropics

Sip piña coladas

Shorty I could take you there

Or we can go to the slums

Where killas get hung

Shorty I could take you there

You know I could take ya (I could take ya…)

I could take ya (I could take ya…)

Shorty I could take you there

You know I could take ya (I could take ya…)

I could take ya (I could take ya…)

Shorty I could take you there

Baby girl I know it’s rough but come wit me

We can take a trip to the hood

It’s no problem girl it’s my city

I could take you there

Little kid wit guns only 15

Roamin’ the streets up to no good

When gun shots just watch us, run quickly

I could show you where

As long you’re wit me

Baby you’ll be alright

I’m known in the ghetto

Girl just stay by my side

Or we can leave the slums go to paradise

Babe it’s up to you,

It’s whatever you like

So rather than having any real commentary on slums, the slums become a site to reinforce the idea that women should align with a man to protect them. The slums are just a backdrop for Kingston to impress a hot woman by being able to take her into an exotic world and keep her safe…from all the aggressive, mean Black men they encounter.

Ben continued,

My friend is traveling in Uganda and was reminded of this song when staying in Atiak, site of a gruesome massacre…His comment was: “I thought of Lam, who has dedicated his life to improving this place, to giving his people a future, and finally, of [Sean Kingston], whose highest ambition is to impress girls by taking them on a tour of places like Atiak. What a stupid song.”

Thanks, Ben!

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.

The image below is from the latest episode of Britain’s Next Top Model (image found here). I would comment, except I just recently wrote almost exactly what I would write for this post here. You might also want to look here and here and here and also here for historical context.

Dude, we are so not making this stuff up.

Thanks to an anonymous tipster in our comments! Don’t forget you can always email us tips at socimages@thesocietypages.org.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Pam Oliver sent in this graph that shows disparities in Blacks’ and Whites’ new prison sentences:

While blacks are more likely to be sentenced for all the offenses shown, clearly drug offenses stand out as the area with the biggest racial disparity in prison sentences. The other thing that stands out is the huge jump that occurred in the late 1980s and how much higher the disparity was by the 1990s than in the 1980s. Either African Americans suddenly started doing a whole lot more drugs, Whites stopped doing them altogether…or Blacks started getting arrested and sentenced at a much higher rate than Whites for drug offenses.

From an article by Oliver:

…the rise in imprisonment since the 1970s is not explained by crime rates, but by changes in policies related to crime…Determinate sentencing, which eliminates judicial discretion, longer sentences for drug offenses, increases in funding for police departments and large increases in prison capacity, the exacerbation of racial tensions and fears following the civil rights movement and the riots of the 1970s, and the politicization of crime as an election issue all seem to have played some role.

In Focus 21 (3) pp. 28-31 Spring 2001.

Other sociologists have pointed out that Whites tend to sell drugs inside buildings (houses, dorm rooms, workplaces) to people they know, while Blacks are more likely to engage in open-air sales to strangers. It’s much easier for police to see and arrest people engaged in open-air sales because they’re visible and, being out in public, can often be stopped and frisked without a warrant. Clearly it would be more difficult to know about drug sales taking place in private residences, and there would be more procedural hurdles to searching for them. And when you’re selling to strangers, you’re more likely to see to an undercover cop or to sell to people who don’t really have a problem saying who they bought their drugs from. So the very manner in which they sell makes it much more likely that Blacks will be caught and arrested, even though enormous amounts of drugs are bought and sold by Whites.

You can find a lot more graphs and articles on this topic (including disparities broken down by state) at Pam Oliver’s website. Also see this post about international imprisonment rates. Thanks, Pam!

Oh, and Lisa’s at the American Sociological Association meetings, which is why you’re stuck with just me this week.

Did you know that the U.S. has a higher imprisonment rate than even Russia? And the U.S. imprisonment rate is about six times that of many European countries.

(This first figure was made by Kieran Healy.)

When and how did this happen? It started in the 1980s with Reagan’s “war on drugs.” The figure below shows the increase in the incarceration rate beginning in the 1980s (# of people out of 100,000).

So our imprisonment rate is the result of imprisoning people who break drug laws, NOT violent criminals or even people who commit property crimes. The increase is largely due to more aggressive policing of drug law violations.

And, as you can see in the figure below, the aggressive policing of drug law violations can be found disproportionately in black neighborhoods. (White and black people take drugs at a very similar rate, but black neighborhoods are more heavily policing and drugs more common among blacks than white have carried heavier sentences — i.e., crack versus cocaine until recently). This figure shows that the increase in the incarceration rate is mostly an increase in the black incarceration rate.

Thanks to the amazing Pam Oliver for reminding me that this last graph comes from her work on the incarceration rate (found here).

This is the fourth installment in a series on why and how people of color are included in advertising aimed primarily at white people. In the first installment, I argued that people of color are included in such advertising in order to associate the product with a racial stereotype (i.e., hipness, intelligence). In the second, I showed how people of color can be used to give a product “color” or “flavor.” And, in the third, I argued that people of color are used to invoke ideas of “hipness,” “modernity,” “progressive” politics and other related ideas. In this post, I suggest that people of color are used to trigger the idea of human variation itself.

In this first ad the idea that each body is different is illustrated by including women of different fitness levels, ages, and races.

In this ad, Levi’s uses a woman who appears Latina to sell their jeans, which come in various fits because there is “a style for every story.” The idea is that people are different; not everyone wants the same cut of jeans.

In this Toyota ad, the copy says “For every expression, there’s a Toyota.” People are unique and so, apparently, are Toyotas. Race is used to communicate the notion of human diversity.

This is an ad for Playtex bras with half sizes. The implication is that people’s bodies are more variable than the A, B, C etc sizes suggest, so half sizes accomodate that variety. I think this ad is particularly interesting because the model is racially ambiguous. Maybe she’s half Asian, Latina, or white, and she’s being used to sell a product that now comes in half sizes.

NEW:

Next up: Including people of color so as to suggest that the company is concerned with racial equality.

See the other posts in the series:

(1) Including people of color so as to associate the product with the racial stereotype.

(2) Including people of color to invoke (literally) the idea of “color” or “flavor.”

(3) Triggering ideas like “hipness,” “modernity,” and “progress.”

In his book Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism (2005; New York: Touchstone), James Loewen discusses cities that had a “no Blacks after dark” policy. They were called “sundown towns” because African Americans were actively informed that they should be out of town by sundown; if not, they were subject to arrest or violence. Of course, the purpose of these regulations was to keep Blacks from settling permanently in these towns. If they couldn’t be in town limits after dark, they clearly couldn’t live there. Here is an example of a sundown town: this ad encouraging people to move to Siloam Springs, Arkansas, says, over in the lower right corner, “No Malaria, No Mosquitoes, No Negroes.”

Found here.

NOTE: As Mr. Loewen pointed out in a comment, I had originally said he discussed “cities in the South,” as though that was all his book concentrated on. That was poor wording on my part, as I had been reading the sections of the book that covered some areas in the South I was specifically interested in (particularly Oklahoma). I did not mean to imply that sundown towns existed only in the South or that Mr. Loewen only discusses the South.

Ben O. sent in the video for “Take You There,” by Sean Kingston. Ben said, “The premise of Sean Kingston’s song ‘Take You There’ is that driving through slums is a great idea for a romantic date.”

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=axq1jQTk84w[/youtube]

My original thought, before I watched the video, was that maybe Kingston (who, according to Wikipedia, was born in Miami but mostly raised in Kingston, Jamaica) was trying to humanize the kinds of low-income neighborhoods that non-residents often believe are uniformly terrifying and that anyone who would venture there is going to their certain death. Or, if not that, maybe to show some of the horrid realities of living in economically devastated areas.

Then I watched the video. What struck me is how every resident is portrayed as glowering, threatening, and angry; they’re all the stereotype of the aggressive Angry Black Man.

The other thing that’s interesting is the gender elements. First, here are some of the lyrics:

We can go to the tropics

Sip piña coladas

Shorty I could take you there

Or we can go to the slums

Where killas get hung

Shorty I could take you there

You know I could take ya (I could take ya…)

I could take ya (I could take ya…)

Shorty I could take you there

You know I could take ya (I could take ya…)

I could take ya (I could take ya…)

Shorty I could take you thereBaby girl I know it’s rough but come wit me

We can take a trip to the hood

It’s no problem girl it’s my city

I could take you there

Little kid wit guns only 15

Roamin’ the streets up to no good

When gun shots just watch us, run quickly

I could show you whereAs long you’re wit me

Baby you’ll be alright

I’m known in the ghetto

Girl just stay by my side

Or we can leave the slums go to paradise

Babe it’s up to you,

It’s whatever you like

So rather than having any real commentary on slums, the slums become a site to reinforce the idea that women should align with a man to protect them. The slums are just a backdrop for Kingston to impress a hot woman by being able to take her into an exotic world and keep her safe…from all the aggressive, mean Black men they encounter.

Ben continued,

My friend is traveling in Uganda and was reminded of this song when staying in Atiak, site of a gruesome massacre…His comment was: “I thought of Lam, who has dedicated his life to improving this place, to giving his people a future, and finally, of [Sean Kingston], whose highest ambition is to impress girls by taking them on a tour of places like Atiak. What a stupid song.”

Thanks, Ben!

Gwen Sharp is an associate professor of sociology at Nevada State College. You can follow her on Twitter at @gwensharpnv.

The image below is from the latest episode of Britain’s Next Top Model (image found here). I would comment, except I just recently wrote almost exactly what I would write for this post here. You might also want to look here and here and here and also here for historical context.

Dude, we are so not making this stuff up.

Thanks to an anonymous tipster in our comments! Don’t forget you can always email us tips at socimages@thesocietypages.org.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.