It is commonly claimed and, in fact, I have claimed it on this blog (here and here), that the U.S. is especially individualistic. Claude Fischer, at Made in America, puts this assertion to the test. “There is considerable evidence, ” he writes, “that Americans are not more individualistic – in fact, are less individualistic – than other peoples.”

He operationalizes “individualism” as “gives priority to personal liberty” and offers the following evidence.

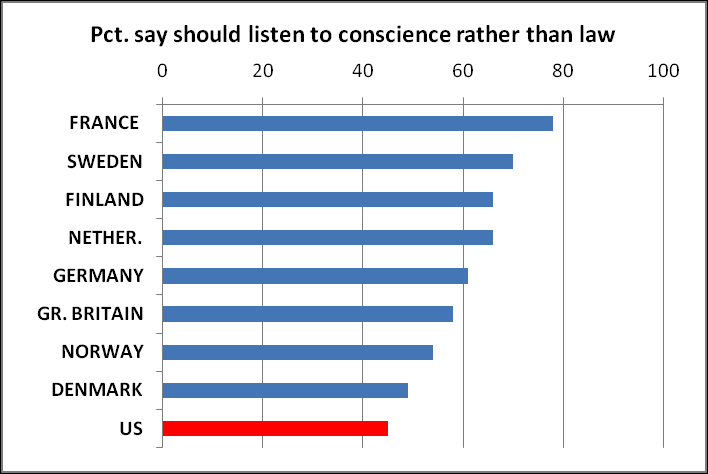

Question: “In general, would you say that people should obey the law without exception, or are there exceptional occasions on which people should follow their consciences even if it means breaking the law?”

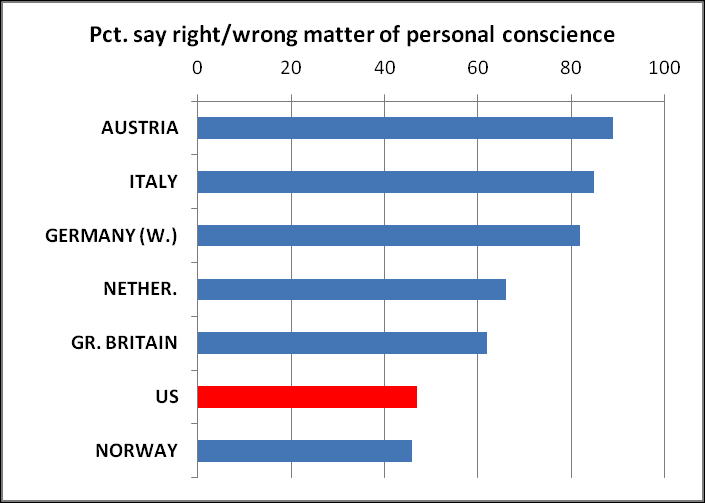

Question: “ Right or wrong should be a matter of personal conscience,” strongly agree to strongly disagree.

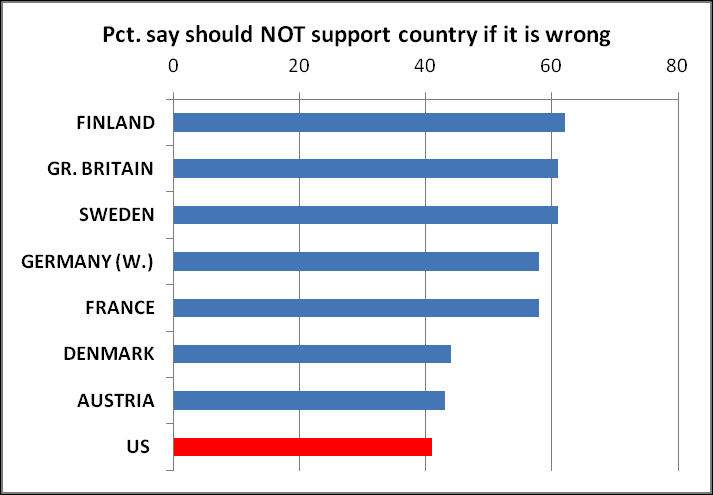

Question: “People should support their country even if the country is in the wrong,” strongly agree to strongly disagree.

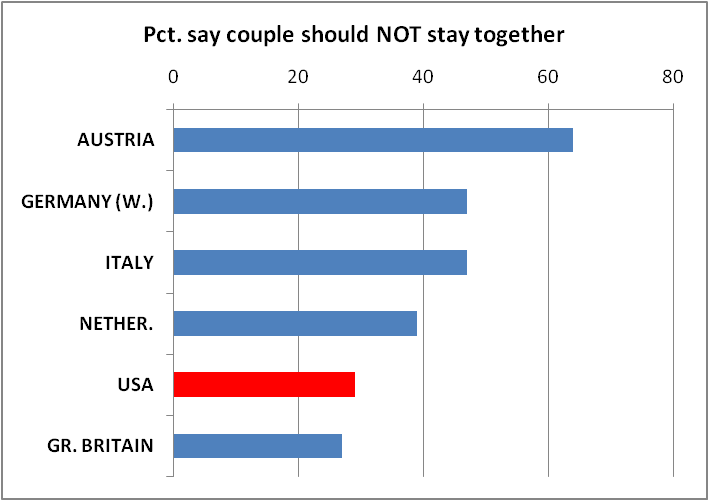

Question: “Even when there are no children, a married couple should stay together even if they don’t get along,” strongly agree to strongly disagree.

Fischer entertains several explanations for these findings.

(1) Americans aren’t really individualistic (anymore).

(2) Americans means something else by individualism (like freedom from government or pulling yourself up by your bootstraps). Fischer thinks that these are different values, though: anti-statism and laissez-faire, pro-business economics.

(3) Americans are individualistic, but they are also religious and sometimes religion outweighs individualism. If that’s so, Fischer argues, then maybe it is true that we’re not that individualistic.

(4) American individualism is found not in people’s opinions, but in how we organize our society. Fischer calls this “undemocratic libertarianism.”

Finally, (5) maybe what is meant by individualism is really voluntarism, the right to leave and join groups as we see fit.

The argument and the answers clearly revolve around how we define (or operationalize) “individualism.” In any case, the comparative data does put the U.S. into perspective and Fischer’s discussion leaves a lot to unpack.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.