This month I enjoyed a lovely week with my mother and step-father, during which we drove down to Key West, FL. Flipping through the tourist book in the hotel, I was surprised to see this:

I’ve been writing for Sociological Image for over six years now and, as a result, it takes a lot to shock me. Well, you got me, Ripley’s! I did not know that we were still marketing racial or ethnic others as “oddities.” At least not this blatantly.

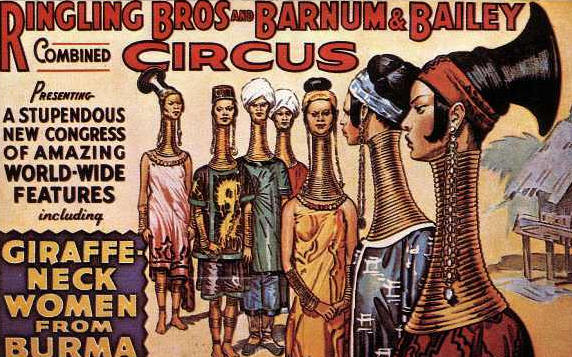

The women who have historically practiced this neck lengthening illusion (what you are seeing is a depressed collar bone, not a longer neck) are a Burmese ethnic minority called Kayan or Padaung. As late as the early 1900s, Europeans and Americans were kidnapping “Giraffe-necked women” and forcing them to be exhibits in zoos and circuses. Promotional materials from that era look similar. Here’s an example:

By the way, Kayan women weren’t the only humans kept in zoos.

I knew that Westerners still traveled to the communities where Kayan people live to see them “in their natural habitat” (sarcasm) and I’ve argued previously that this is a case of racial objectification. I had no idea, however, that we still featured them as grotesque curiosities. Ripley’s Believe It or Not!: “Proudly freaking out families for over 90 years.” Taking that tradition thing really seriously, I guess.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.