“Advocates might want to try different language (or a different approach) in their campaign to reform the criminal justice system,” writes Jamelle Bouie for Slate. He drew his conclusion after summarizing a new pair of studies, by psychologists Rebecca Hetey and Jennifer Eberhardt, looking at the relationship between being “tough on crime” and the association of criminality with blackness.

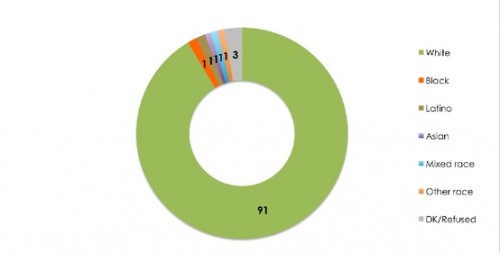

In the first study, 62 White men and women were interrupted as they got off a commuter train and invited to chat about the three strikes law in California. Before being presented with an anti-three strikes petition, they were shown a video that flashed 80 mugshots. In one condition, 25% of the photos were of black people and, in another, 45% of the photos were.

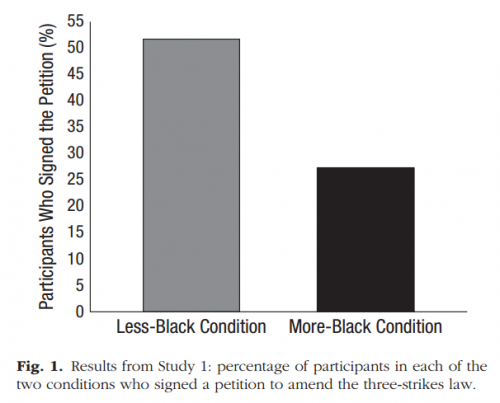

Among the subjects in the first “less black” condition, more than half signed the petition to make the law less strict, but only 28% in the “more black” condition signed it.

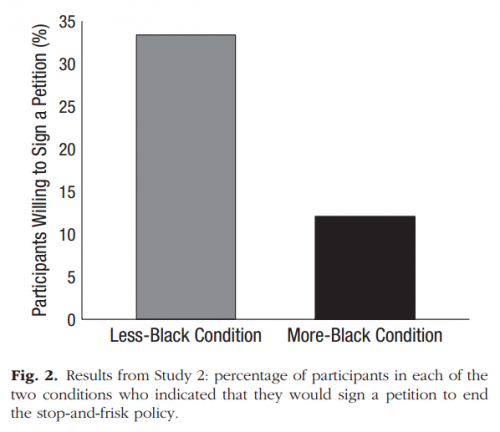

A second study in New York City about the stop-and-frisk policy had a similar finding:

The results suggest that white Americans are more comfortable with punitive and harsh policing and sentencing when they imagine that the people being policed and put in prison are black. The second study suggested that this was mediated by fear; the idea of black criminals inspires higher anxiety than that of white criminals, pressing white people to want stronger law enforcement.

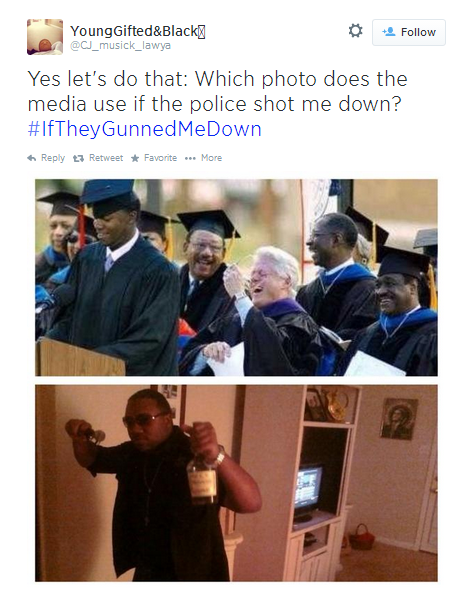

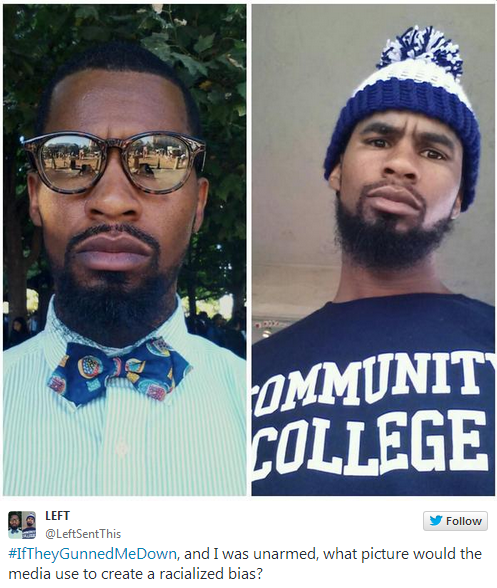

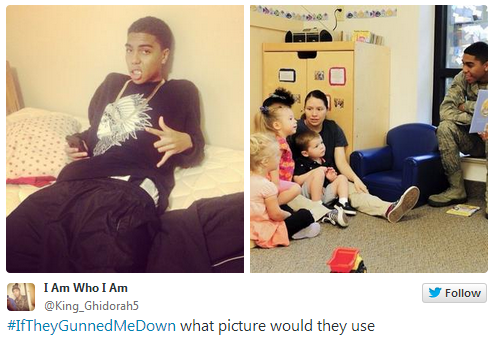

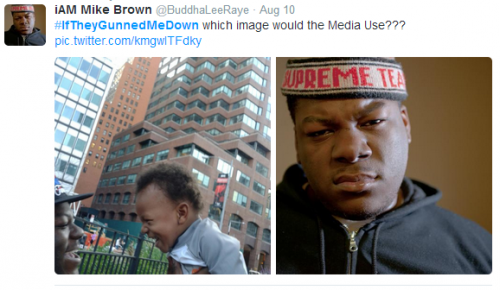

So, as Bouie concluded, when prison reformers and anti-racists point out the incredible and disproportionate harm these policies do to black Americans, it may have the opposite of its intended effect. Hetey and Eberhardt conclude:

Many legal advocates and social activists assume that bombarding the public with images and statistics documenting the plight of minorities will motivate people to fight inequality. Our results call this assumption into question. We demonstrated that exposure to extreme racial disparities may make the public less, not more, responsive to attempts to lessen the severity of policies that help maintain those disparities.

“Institutional disparities,” they add, “can be self-perpetuating.” Our history of unfairly targeting and punishing black men more than others now convinces white Americans that we must continue to do so.

Cross-posted at Pacific Standard.

Lisa Wade, PhD is an Associate Professor at Tulane University. She is the author of American Hookup, a book about college sexual culture; a textbook about gender; and a forthcoming introductory text: Terrible Magnificent Sociology. You can follow her on Twitter and Instagram.